DIXON — In our previous column, we told the story of Charles Russell Lowell’s 1859 purchase of the 201 acres next to Hazelwood. His family donated this acreage to Dixon in 1907, and this natural wonderland became “Lowell Park.” Many are not aware that these acres hold some remarkable historical gems.

[ A piece of Dixon history: Was Lowell Park inspired by Walden Pond? ]

The first gem predates Lowell and even predates when “Father” John Dixon arrived here in 1830. Around 1827, John Dixon’s brother-in-law, Oliver W. Kellogg, blazed his famous trail through these acres when he carved northern Illinois’ very first path from Peoria to Galena.

Kellogg’s lost ruts of history

Traveling upon Kellogg’s Trail, the wagons and stagecoaches of hundreds of early settlers scored deep ruts into the path. In 1941, a Lowell Park historian reported that the park’s “greatest historical importance” is “the deep ruts of the old … trail to Galena still plainly visible between the south road and the Pinetum.”

:quality(70)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/shawmedia/DUNA5NVH3BAFHLFAWROOZXIWR4.JPG)

My great aunt, who died 20 years ago, also testified of these ruts. Today, however, the “deep ruts” are not “plainly visible.” But if you know where they are, please let me know.

On the main road into today’s park, about 100 yards east of the Nature Center, a historical marker identifies a likely spot where Kellogg’s Trail crossed through the acreage. The trail then continued in a north-northwesterly direction on its way to Galena.

A second historical gem

In addition to this historic trail, a pioneer home stood on this property long before Lowell purchased it in 1859. In 1836, John and Ann Richards came to Dixon’s Ferry from Chicago, a journey that took four and a half days by covered wagon.

When they arrived with their five children on Sept. 1, 1836, Ann Richards said, “Where’s the town?” At that time, only 11 buildings made up the entirety of the village.

Tragically, their 18-month-old child died a week later and became the third person buried at Oakwood Cemetery. For that first winter, the family obtained temporary lodging in Dixon’s little settlement.

In the spring in 1837, John Richards constructed a frame home in the woods, which later became the northwest portion of Lowell Park. The location offered the protection of the woods, some nearby farmland (which later became the park’s Pinetum), and it was just steps away from Kellogg’s Trail, offering a convenient pathway to Dixon and other early settlements in northwestern Illinois.

Connected to Dixon and Illinois history

In their first year, John and Ann Richards were among the four founding families of the town’s first Methodist church, which organized on May 7, 1837. Known to be hospitable to travelers, the Richards family often gave lodging to Methodist ministers traveling through the area.

In 1837, their country home also provided lodging for Judge Thomas Ford, who spent several days with their family. Ford soon became famous; he was elected governor of Illinois in 1842.

The Richards family built strong relationships in Dixon. William Richards, their son, married Henrietta Dixon, John Dixon’s granddaughter. Henrietta holds the distinction of being the “first white baby” born in Dixon.

Today, the location of the Richards home – with its original cellar – is noted by a historical marker near the Vaile shelter in the park.

Designed by renowned architects

Now, historical gem No. 3. When Carlotta Lowell gave the land to the city in 1907, she hired the renowned Olmsted Brothers of Brookline, Massachusetts, to design the park.

Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. had established Harvard University’s first landscape architecture program. He was the son of Frederick Law Olmsted, who is regarded as “the father of American landscape architecture.”

The Olmsteds sent Arthur C. Comey, a fresh 1907 graduate of Harvard’s landscape architecture program, to Dixon for two years to study the property and craft his recommendations. The Dixon park board, impressed by his work, hired Comey to be the first park superintendent.

Harmonizing with the woods

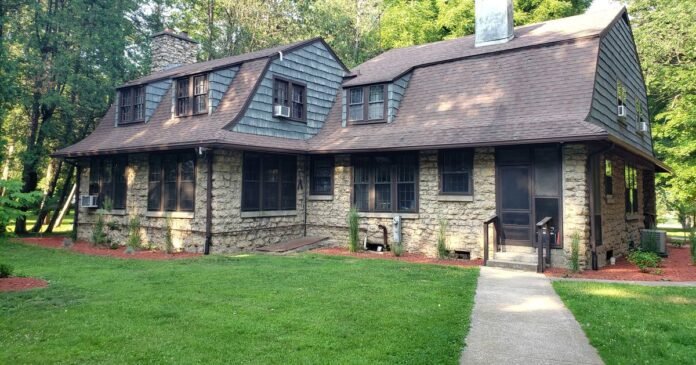

Comey felt that building the caretaker’s home was a crucial first step. In keeping with Olmsted principles, he created the home with a design that “does not call attention to itself” and that “works on the unconscious to produce relaxation.”

That home is Woodcote. When completed in September of 1909, Woodcote was described as “something entirely new and novel in park homes.”

While designing the park’s unique shelters, Comey said, “These shelters should be simple yet substantial and picturesque, but without ornamentation. They should be rather dark in color so as to harmonize with the woods.”

The quarry in the middle of the park served as the source for the stone used to create these shelters as well as Woodcote and the large stone pillars at the entrance. By Comey’s design, these structures emerged from the natural wood and stone found within the park itself.

The celebrated Olmsted, Comey and Simonds

Arthur C. Comey’s work and vision can be found on many of the park’s popular features, including the Pinetum, the well house, the overlook, the boat docks, and the location of the roads that curl creatively through this haven of nature.

In late 1909, Comey returned to Cambridge, Massachusetts, where he taught at Harvard and soon became a nationally renowned landscape architect who published widely. But his very first professional employment was here in Dixon as Lowell Park’s designer, its first superintendent and the first resident of Woodcote.

:quality(70)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/shawmedia/4GQK7EUGJRFDRJUE6ODHGHB7WM.jpg)

The park board then hired O.C. Simonds, another prominent landscape architect, to supervise the park’s development for the next two decades. Simonds also became renowned nationally; Chicago’s Lincoln Park and the Morton Arboretum are among his famous projects.

Around 2006, the park board applied to place Lowell Park on the National Register of Historic Places. When the reviewers saw that the celebrated names of Olmsted, Comey and Simonds had developed the park, Lowell Park was quickly and officially added to the Register, just in time for its 2007 centennial.

- Dixon native Tom Wadsworth is a writer, speaker and occasional historian. He holds a Ph.D. in New Testament.