The world of literature has turned purple, not knowing which color, blue or red, fits the current dilemma that’s causing serious students of the art to tear their hair out. The age of social media has opened the door to a cascade of new challenges to literary freedom that stifles creativity.

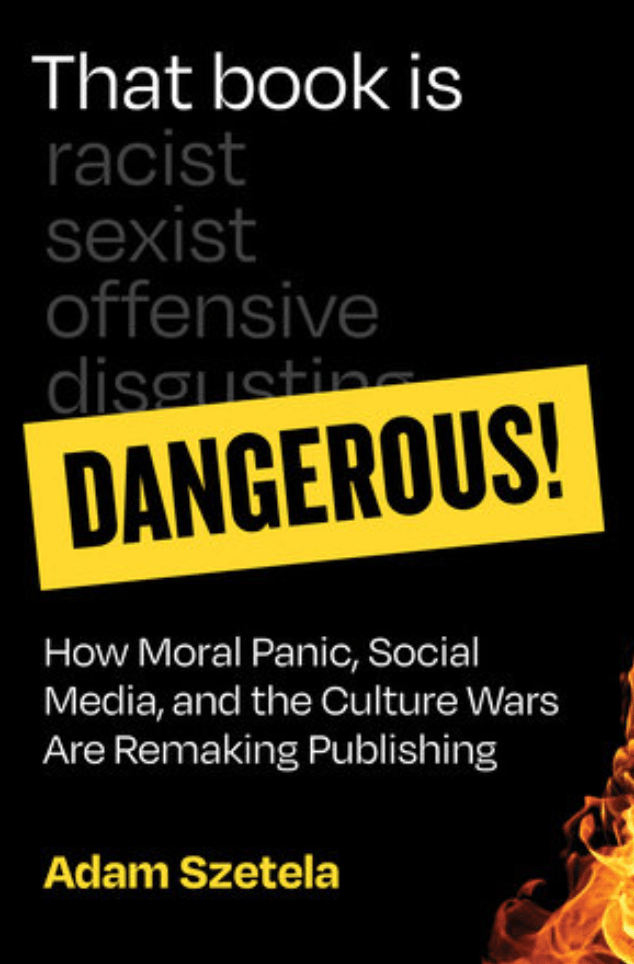

Answers for what ails literature in today’s complicated world can be found in an upcoming new book: That Book is Dangerous (The MIT Press, 2025) by Adam Szetela, PhD candidate in the Department of Literature in English at Cornell University.

That Book is Dangerous is scheduled to be published for purchase on August 12, 2025.

Szetela frames the current literature conundrum as follows: “At a moment when people are focused on the right’s moral panic over literature, it might seem strange that this book focuses on the left’s moral panic over literature. After all, right-wing panic has had more influence at the legislative level. That is true. But left-wing panic has had significantly more influence inside publishers, agencies, and other corners of literary culture. This is the reason why many of the progressives I interviewed are more concerned about the left than the right. While the right is remaking the world in its image, the left is standing in a circular firing squad.”

Szetela interviews people at the highest levels to discover massive self-censorship happening behind closed doors inside publishers, literary agents and other primary movers and shakers that publicly claim to be advocates of “free speech.” In contrast, he discovers a backhanded autocracy in publishing, making one wonder where the spirit of liberal democracy truly resides, if at all. Authors are subject to intimidation and dictates as to the meaning of content of their writing on a broad scale in this strange new breed of censorship hidden from public view.

Szetela gives an example of the horrors of trying to get a book published in chapter one, a YA author’s unpublished book caused an uproar on Twitter by people who had never read the book claiming it was racist because the ‘setting’ of the book was a fantastical world where oppression was not based upon skin color, therefore considering it anti-black by depicting slavery that was not African American slavery. The distressed, horribly harassed author canceled publication. The New York Times, at a later date, reported the book was to be published, but only after scrutiny by “sensitivity readers” to check for potentially offensive material.

According to the Szetela’s investigations, there’s an epidemic of mandatory sensitivity readings, plus demands to sign morality clauses in contracts as well as outright censorship of “dangerous” books in the name of antiracism, antifeminism, and other social norms affecting social justice. Much of this is an outgrowth of the new world of open internet exchanges of public outcries on X, Goodreads, Change.org, and other online platforms where authors are accused of racism, sexism, and homophobia, whether truly justified or not, whether reading the book or not, harsh consequences follow in the footsteps of clues as to content of a proposed book. It’s a form of mass public censorship based upon inuendo, guesswork, and misdirected testosterone.

Szetela’s book describes a national “moral panic” within the clutches of a moral crusade not all that different from the 1950s crusade to censure those who wrote and illustrated comic books as concerned adults pressured publishers and the U.S. Senate to censure distasteful material. Comic book burnings ensued in Chicago, Memphis, Port Huron, Cape Girardeau, and Binghamton, among others. Szetela’s simile explains it best: “When literature is treated as an immoral disease that is spreading like the plague, censorship is the only answer.”

This Orwellian intervention into YA and children’s literature appears to be now leaking into adult literary culture. for example, journalists at The New York Times have demanded sensitivity readers to ensure they do not offend readers; this shocker, as footnoted in the book, described in an article by Glenn Greenwald: “The New York Times Guild Once Again Demands Censorship of Colleagues.”

This bastardized moral crusade cruising throughout society is a piece of cake for anybody willing to get involved. Anyone with internet can be a moral crusader. No credentials necessary. Disturbingly, “research shows that expressions of moral anger and disgust, two emotions central to moral crusades, are associated with more retweets.” Even the most uniformed readers have an audience. The world of book reviews has turned into whack-a-mole amateur hour, as explained by one publisher: “People like a sensationalized story in our new world. An opinion can spread so quickly. I had a conversation last week about what we can do about Goodreads. How do we even know a review is real? It’s crazy. If it’s a negative response, it could kill a book.”

Open platforms have placed the world of intellect, of professional study, of publishing, of teaching in a strange new world that diminishes, sometimes obliterates, the search for true truthfulness. “The prevalence with which people freely admit they never read, nor have any intention of ever reading, books they passionately criticize is another indicator of how decrepitly anti-intellectual literary culture has become… the decline of reading — through skim reading, rushed reading, or not reading at all— is a perennial feature of the dystopian genre.” Ignorant, idiotic, silly, lunatic, stupid blabbering fools all have an official platform in today’s upside-down world.

The moral crusade has created a monstrosity of checks and balances that homogenizes literature while downsizing authors. A large cadre of sensitivity readers has sprung forth within only a few years. These are self-declared experts who ensure literature is not offensive, now being hired by Penguin Random House, HarperCollins, and other major publishers.

Additionally, publishers now include “morality clauses” in contracts. These contracts specify that the publisher may terminate a contract if the author’s conduct evidences a lack of due regard for public conventions and morals. Taking matters to the highest road, The Times has established a ‘sensitivity hotline’ for journalists to report on one another like tattletales found in children’s literature. And writers for The New Yorker have discovered morality clauses in their contracts that are wide open for abuse as the clauses state writers can be terminated if the writer “becomes the subject of public disrepute, contempt, complaints or scandals.” What’s missing, if anything, from this list of misdemeanors? According to “Jeannie Suk Gersen, a law professor at Harvard University: ‘No person who is engaged in creative expressive activity should be signing one of these.” (pg. 185)

As described by Szetela: “The left’s approach to literature looks like the right’s approach to crime. On both sides, adults see themselves as punitive moral leaders who protect the rest of us from harm.” Fascinatingly, “there is a culture war between the punitive moral framework of the right and the compassionate moral framework of the left… These liberals are a real problem for the progressive movement.”

In the final analysis, Szetela emphasizes people must stand up to this cultural flap and resist: “In Fahrenheit 451, a retired English professor warns us: ‘I saw the way things were going, a long way back. I said nothing. I’m one of the innocents who could have spoken up and out when no one would listen to the ‘guilty,’ but I did not speak and thus became guilty myself. And when finally, they set the structure to burn the books, using the firemen, I grunted a few times and subsided, for there were no others grunting or yelling with me. By then, it’s too late.” (pg. 195)

Adam Szetela:

”A deluge of books have been canceled, rewritten, and otherwise censored in the past decade. My goal was to expose the current threats to literary freedom; where they came from, how they have reshaped publishing, and so on. That said, my book shows that much of this censorship occurs because people are scared to stand up to the censors. That culture of acquiescence needs to end.”

World State (Brave New World, 1932)

Ministry of Truth (Nineteen Eighty-Four, 1949)

Truth Social (Trump Media, 2022)

Robert Hunziker

Los Angeles