Review by Chris MacKenzie

It is as Winston Churchill put it “a riddle wrapped in a mystery, inside an enigma” how Scotland came to be the only nation that is, not just instantly recognisable, but also largely defined by, in global terms, the image of a musical instrument, and that against Ireland which has a musical instrument as its national symbol.

The story of why a small outpost on the outskirts of Europe should produce the dominant bagpipe amid the legions of bagpipes that have existed, and in many cases still do exist, is so complex it makes a Sherlock Homes case read like a Ladybird book. It’s a story with a cast to rival Ben Hur, featuring family dynasties, clans, lords and ladies, queens, the army, the British Empire, great writers, the Scottish diaspora, romanticism, the supremely talented, the supremely opinionated, the insane, and war, lots of war, to cite but a few of the reasons the Great Highland Bagpipe has conquered the world and is Scotland’s talisman the world over.

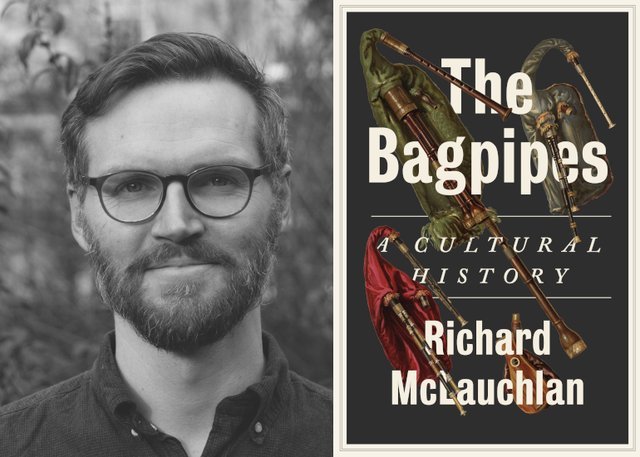

It is into the morass of fact and fiction that Richard McLauchlan plunges, with his new book The Bagpipes. A Cultural History. His aim to ‘tell the story of the bagpipes in an historically accurate way but to keep the romance and magic alive”. That last piece is crucial as it is all to easy for books on piping to fall into turgid, almost biblical, tutelage lineages. McLauchlan avoids this and steers clear of the wilder legends associated with pipers, and pipe tunes, by keeping to the facts as much as possible. This being the story of the bagpipes, and of course the pipers, the facts are strange enough to make the book highly entertaining.

McLaughlan takes us on a brief journey from the very earliest references to bagpipes, featuring, of all people, Emperor Nero, through the ebbs and flows of early European history and the accompanying piping soundtrack on the vast array of bagpipes across the continent to bring us to a nebulous point where bagpipes were clearly everywhere, but quite how they morphed into the Great Highland Bagpipe is lost in the great glen of time. MacLaughlan argues England and especially Ireland had crucial roles in the establishment of piping north of the tweed. As McLaughan picks his way through the evidential slim pickings, he is careful to bring the bellows pipes into the equation and view the early development as integral part of how piping evolved in the following centuries. This echoes the current sentiment that there were big pipes and wee pipes and big music and wee music concurrently, and pipers switched between them as the occasion demanded.

As the chronology moves on to firmer ground he inevitably has to tackle the thorny question of Piobaireachd, as he comments “this remarkable music”. Again, he takes a broader view, including an Irish influence on its creation, and giving room to those voices offering a critique on the way it is played today. All of this is done in a reader friendly way without reference to dre, edre or crunluath a mach.

This even handedness is a feature of the book as McLaughlan works hard to be fair and take a broader view on the history of the bagpipes, and his sources are meticulously noted. A good example is the Jacobite rebellion where he notes that there were likely pipers on the government side, as well as the Jacobite side. As he moves into the latter half of the eighteenth and early nineteenth century McLaughlan shows that the bellows pipe in various forms was the dominant bagpipe across Europe and indeed there was a large degree of musical intermingling across regions, “any claims about hermetically sealed repertoires for the respective regions – one abounding in piobaireachd and the other delighting in ‘lighter’ forms of music – are hard to maintain.” This post Culloden period saw the formation of the Highland Societies of London, the first competitions and the publication of the first printed pipe scores, and, of course, the formation of, and recruitment into, the Highland regiments. McLaughlan deals with them all and tackles the issues of cultural impact and musical alteration head on.

The war years see tales of heroic pipers, Findlater, Laidlaw, Anderson, and Millin among many others, set against the insanity of putting pipers front and centre in the wars up to and including WWI. McLaughlin corals the well kent stories into a broader narrative where the Great Highland Bagpipe is taken across the world where it sometimes stayed, Sialkot in Pakistan is the worlds largest producer of bagpipes, but always implanted an image that was to linger long after the troops had gone.

The post WWII piping scene is one of almost complete dominance of the Great Highland Bagpipe. Mclaughlan tackles the thorny subject of the College of Piping co-founder Seumas MacNeil (Thomas Person was the other founder) whose memory is both respected and disliked in the piping world. McLaughlan weighs the arguments while also sharing some lesser-known facts of the college’s early days. Women in piping and the role of misogyny in the piping world, piping in Nova Scotia, the crucial formation of the Lowland and Border Piping Society, the significant impact of players such as Gordon Duncan and Martyn Bennett are all discussed. McLaughlan comes right up to date, while naming the most famous piper in the world, and also tries to sum up the state of piping today. That is no easy task, but he has a very good attempt at it.

Those with shelves groaning with old copies of the Piping Times and copies of Donaldson, Manson, Murray, MacKenzie and Cannon will be familiar with many of the stories in this book, but McLaughlan looks to take those stories, and often the counterpoint to them, and provide the broader picture of the impact on the piping consensus. He does this in a highly readable way, while creating a very accessible history of the bagpipe in Scotland without ever losing the rigour required to provide a warts and all story. His aim was to “keep the romance and magic alive”, which he does without reference to Silver Chanters and Fairy Caves, a testament to both his penmanship, and the genuine romance and magic that goes hand and hand with the bagpipes.

The Bagpipes. A Cultural History by Richard McLauchlan is available from C.Hurst & co (Publications)