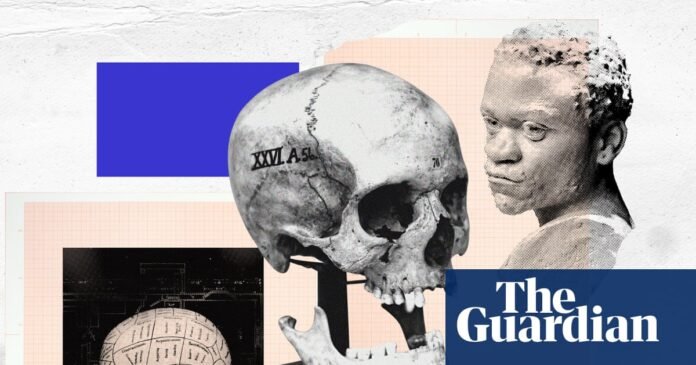

Phrenology was long ago added to the junk heap of discredited theories. But in the 200 years since the Edinburgh Phrenological Society turned this pseudoscientific method to study the skulls of black Africans, Indians and white Europeans, scientific racism has continued to re-emerge in different guises.

In the 19th century, as scientists were intent on classifying the natural world into taxonomic categories, some of Edinburgh’s most celebrated intellectuals argued that different human races were so distinct that they ought to be considered separate species. The University of Edinburgh report on its legacy of links to slavery and colonialism notes that non-white populations were invariably depicted as inherently inferior, offering a convenient justification for colonialism.

As this view became untenable, scientific racism shifted into the domain of eugenics in the 20th century. Francis Galton, the English statistician who coined the term, argued for social measures aimed at “improving the stock”. Edinburgh’s then chancellor, the former Conservative prime minister Arthur Balfour, was a prominent supporter and became honorary vice-chair of the British Eugenics Education Society in 1913.

In the US, eugenics inspired forced sterilisation programmes, which disproportionately targeted African American women and, in Nazi Germany, was the ideological backdrop to the Holocaust.

The advent of modern genetics and human population data has shattered the idea that there are biologically distinct groups, or that humans that can be neatly categorised based on skin colour or external appearance. Genetic variation between populations is continuous and does not align with social, historical and cultural constructs of race. Race, as a genetic concept, does not exist.

Yet, says Angela Saini, author of a book on the return of race science, “people don’t stop believing falsehoods just because the evidence suggests they are wrong”. As IQ testing became the metric of choice for those seeking to draw conclusions about racial differences – often based on biased or fraudulent datasets – old, discredited arguments resurfaced.

The Bell Curve, a 1994 bestseller, argued that IQ was heritable and unequally distributed across racial groups. At the University of Edinburgh, students boycotted the lectures of Christopher Brand, a psychology professor, in which he claimed a genetic basis for white intellectual superiority. After he repeated these arguments in his 1996 book, The g Factor (and stoked further controversy by defending paedophilia), Brand was eventually dismissed, while his book was withdrawn and pulped.

With the recent rise in ethnic nationalism and the far right globally, a resurgence of interest is under way into theories of racial exceptionalism. Last year, the Guardian revealed that an international network of “race science” activists, backed by secret funding from a US tech entrepreneur, had been seeking to influence public debate. Discredited ideas on race, genetics and IQ have become staple topics of far-right online discourse.

“The ideas have absolutely not changed at all,” says Prof Rebecca Sear, an anthropologist at Brunel University of London and president of the European Human Behaviour and Evolution Association. “If you can provide a measurement – IQ, skull size – that helps give racism a respectable gloss.”

Just like phrenology, Sear says, a lot of contemporary scientific racism is simply “shockingly bad science”. But when communicated in the form of a graph or chart – whether in a 19th-century lecture theatre or on social media today – pseudoscience and credible science can look similar.

“I would love to see a world in which people stop turning to biology to explain socioeconomic and cultural differences, in which nobody is judged by their racial classification,” says Saini. “But the University of Edinburgh report is a reminder of how even seemingly smart, educated people can come to believe ridiculous things.”