Researchers have long suspected that the connection between our gut and brain plays a role in the development of Parkinson’s disease.

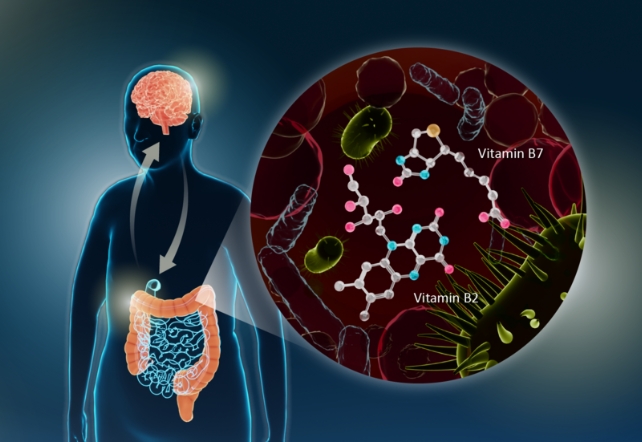

A recent study has identified gut microbes likely to be involved and linked them with decreased riboflavin (vitamin B2) and biotin (vitamin B7), pointing towards a surprisingly simple treatment that may provide help: B vitamins.

“Supplementation of riboflavin and/or biotin is likely to be beneficial in a subset of Parkinson’s disease patients, in which gut dysbiosis plays pivotal roles,” write Hiroshi Nishiwaki and colleagues, medical researchers from Nagoya University, in their paper published in May.

The neurodegenerative disease affects almost 10 million people globally, who can expect at best therapies that slow and alleviate symptoms.

Symptoms usually start with constipation and sleep problems, up to 20 years before progressing into dementia and the debilitating loss of muscle control.

Previous research has found that people with Parkinson’s disease also experience changes in their microbiome long before other signs appear.

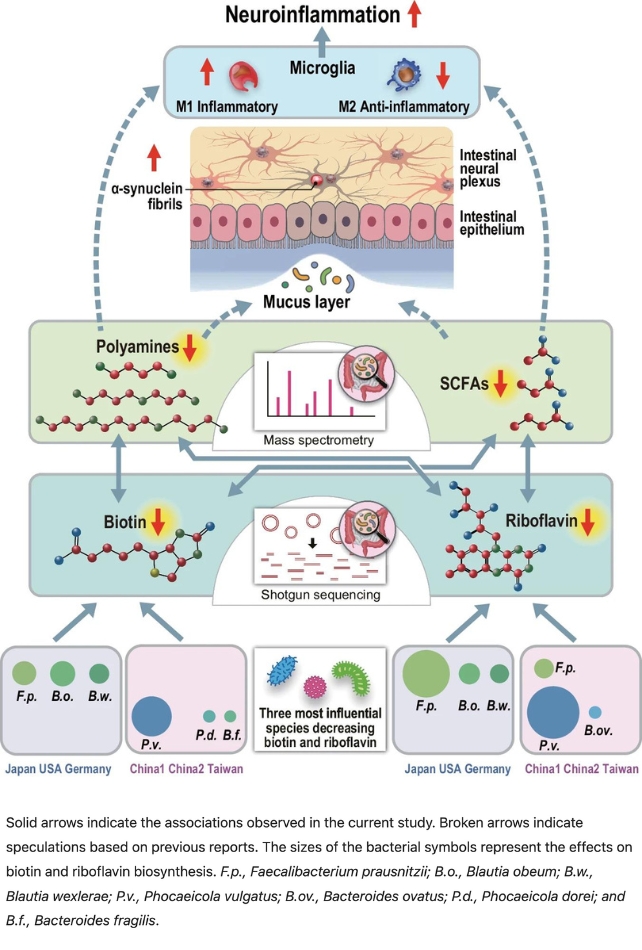

By analyzing fecal samples from 94 patients with Parkinson’s disease and 73 relatively healthy controls in Japan, Nishiwaki and team compared their results with data from other countries like China, Taiwan, Germany, and the US.

Although different groups of bacteria were involved in the various countries examined, they all influenced pathways that synthesize B vitamins in the body.

The researchers discovered that changes in gut bacteria communities were associated with a reduction in riboflavin and biotin in people with Parkinson’s disease.

Nishiwaki and colleagues then demonstrated that the lack of B vitamins was associated with a decrease in short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) and polyamines: molecules that help create a healthy mucus layer in the intestines.

“Deficiencies in polyamines and SCFAs could lead to thinning of the intestinal mucus layer, increasing intestinal permeability, both of which have been observed in Parkinson’s disease,” explains Nishiwaki.

They suspect that the weakened protective layer exposes the intestinal nervous system to more toxins, such as cleaning chemicals, pesticides, and herbicides, which are encountered more frequently nowadays.

These toxins contribute to the overproduction of α-synuclein fibrils – molecules known to accumulate in dopamine-producing cells in the substantia nigra part of our brains, causing increased nervous system inflammation and eventually leading to the more severe symptoms of Parkinson’s.

A 2003 study found that high doses of riboflavin can help recover some motor functions in patients who also eliminated red meat from their diets.

Therefore, it is possible that high doses of vitamin B could prevent some of the damage, as proposed by Nishiwaki and team.

All this indicates that ensuring patients have healthy gut microbiomes may also be protective, as would reducing the toxic pollutants in our environment.

With such a complex chain of events involved in Parkinson’s disease, not all patients are likely to experience the same causes, so each individual would need to be evaluated.

“We could perform gut microbiota analysis on patients or conduct fecal metabolite analysis,” Nishiwaki explains.

“Using these findings, we could identify individuals with specific deficiencies and administer oral riboflavin and biotin supplements to those with decreased levels, potentially creating an effective treatment.”

This research was published in npj Parkinson’s Disease.

An earlier version of this article was published in June 2024.