Experiencing the traumatic event of running over an animal is difficult for both the animal and the driver. In the USA alone, one million vertebrates are killed in collisions with vehicles every year. This makes roads and highways a threat to wildlife.

Aside from the deaths caused by these accidents, species also face challenges in migrating, reproducing, and finding new feeding areas due to habitat fragmentation. This was the case for the mountain lion population in Los Angeles, which was hindered by road accidents and forced into inbreeding. As a solution, the construction of the largest wildlife bridge in the world began.

The challenge of the 101 highway

The mountainous Santa Monica area in California is home to a variety of wildlife, including big cats, deer, snakes, and lizards. However, these animals must cross the busy 101 highway, where about 300,000 vehicles pass through its ten lanes daily. One famous mountain lion in the area, known as P22, has highlighted the plight of these animals, with around twenty specimens being killed on the highway in the last twenty years.

The Wallis Annenberg Wildlife Crossing

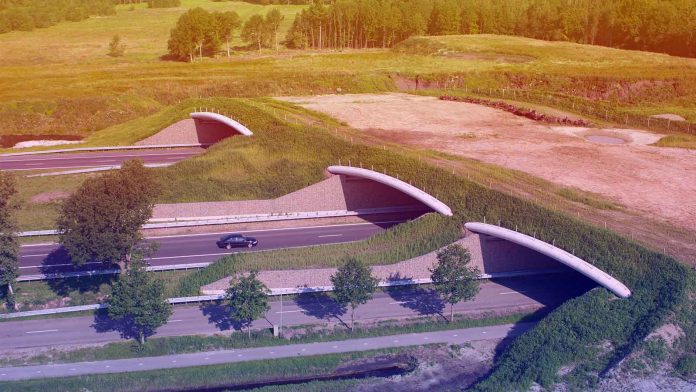

To address this issue, funds were raised to build the Wallis Annenberg Wildlife Crossing, estimated to cost $90 million. This wildlife bridge, which is under construction and expected to be completed by early 2025, will be the world’s largest, measuring 210ft long and 165ft wide. Designed to integrate with the landscape, the bridge will not only provide a crossing for animals but also support local vegetation with its earthen cover.

Specialists in various fields, including mycology, have been involved in studying the terrain and vegetation of the area to ensure continuity with the surrounding natural landscape.

Protecting wildlife by land, sea, and air

Building collisions are not the only threat to wildlife, as birds also face challenges from impacts with building windows. To address this, a new type of glass with tiny “beads” visible to birds has been developed. Additionally, barriers in aquatic environments, such as dams, can disrupt fish migrations. Solutions like the salmon “elevator” in Spain are being explored to help species complete their biological cycles.

Future challenges involve creating more wildlife-friendly constructions and increasing green spaces in urban areas. Integrating vegetation into structures, like the Los Angeles wildlife walkway and the use of tree roots and branches to create living urban elements, are steps in the right direction.

Source: