Nik Slackman speaks with Taylor Lewandowski and Lynne Tillman on the occasion of their new book, “The Mystery of Perception.”

:quality(75)/https%3A%2F%2Fassets.lareviewofbooks.org%2Fuploads%2FMystery%20of%20Perception.jpg)

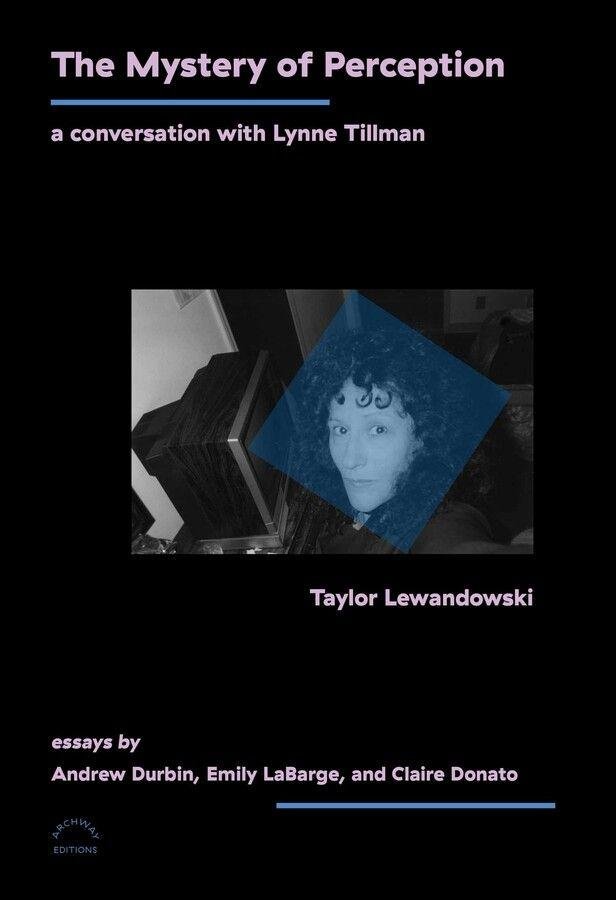

The Mystery of Perception: A Conversation with Lynne Tillman by Lynne Tillman and Taylor Lewandowski. Archway Editions, 2025. 128 pages.

THE AUTHOR Lynne Tillman first encountered young up-and-comer Taylor Lewandowski in 2022, at a reading at New York’s KGB Bar. Tillman, an accomplished novelist and critic, had lived in the city for decades and attended readings at KGB for years; Lewandowski had flown in from Indiana, making time in his busy schedule as a high school English teacher (the bookstore he currently owns and operates, Dream Palace Books, was at that point still just a dream). They read together, and Tillman was impressed by Lewandowski. Afterward, she spoke with him about his piece, which led to a warm, literary conversation over dinner that evening.

Pleasant as the event was, Tillman thought her connection to Lewandowski could have begun and ended there. So, it came as a shock to her to receive a call from him a few months later: “Taylor’s very modest, a little bit shy,” says Tillman. “I knew nothing about him having read anything I had written.” Yet what started as an in-person interview at Tillman’s apartment in April 2023 developed into hours and hours of phone calls—the transcripts of which fill Lewandowski’s new book, The Mystery of Perception: A Conversation with Lynne Tillman. Though the volume centers on Tillman’s life—with essays exploring her work and career by Claire Donato, Andrew Durbin, and Emily LaBarge—it bears the distinct tenor of an intimate exchange. Often, the two writers’ rapport reads like a teacher telling one of her favorite students gossip about his favorite artists (in this case, Kathy Acker, John Cale, and Denis Johnson—to name only a few).

At the same time, as Tillman and Lewandowski grew familiar with one another, their chat took on an almost philosophical quality. Explorations of Tillman’s personal history paved the way for meditations on mortality and legacy. Debates on the existence of a “true self” recurred and developed. What was, initially, a biographical interview becomes, in this book, a discussion that feels closer, stranger, and harder to define than any other I have ever read.

I felt that indefinable quality when I spoke with Tillman and Lewandowski over video calls in January and April of this year, struck by the particular connection these two writers share. When asked, both offered theories for understanding how their unique partnership came to be. Lewandowski referred to his introduction to the book, noting that what he saw as the central question of Tillman’s work—“How do I relate to you?”—makes Tillman a perfect interlocutor. He also concedes to being a big fan: “I definitely look up to you,” he said to Tillman. “In a mentorish way, but not really. Maybe it’s friendship.” Similarly, Tillman observed that their connection “began in an objective way. ‘Who is this person? Why do they want to talk to me?’” But, she said to Lewandowski, as the project continued, “I just liked you. I think if I hadn’t liked you, it would have been very hard to go on.”

I personally don’t know what animates Tillman and Lewandowski’s ineffable draw toward one another. Really, I don’t think they—or anyone else—know, either. It may be a bond deeply indebted to the unconscious, a frequent concern of Tillman’s writing. Reading The Mystery of Perception, one gets the impression that a genuinely unknowable truth—about life, identity, and meaning—lurks beneath the two writer’s words; that unconscious associations (“the unthought known,” as a psychoanalyst might call it) may be driving them, shaping how each sees the other, speaking, of course, to the mystery of perception itself.

My conversations with Tillman and Lewandowski delved into—among other subjects—the lives and legacies of artists, their personal histories, and writing as a form of communicating with the dead. This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

¤

NIK SLACKMAN: Taylor, tell me about growing up in Indiana. Did you start reading Lynne’s work then?

TAYLOR LEWANDOWSKI: I was thinking about this the other day—Lynne, did I ever tell you that, in my formative years, my backyard was a cemetery?

LYNNE TILLMAN: Yes, you did tell me.

TL: From ages one to five, all of my birthdays and hide-and-seek would happen in the cemetery.

Wow.

TL: I would be dropped off by the school bus and walk around in the cemetery as this kindergarten kid. And my parents didn’t care because we lived in the middle of nowhere. My formative years were spent around people buried in the ground, I guess. So, The Mystery of Perception is connected to these things I’ve been thinking about since a pretty young age: talking about these people who have passed, maybe resisting disappearance. It sounds a little corny.

LT: That’s not corny. It’s a beautiful image. I can imagine you as a little tot. You probably didn’t come up to the top of the gravestones.

TL: It wasn’t until my twenties that I started reading Lynne’s work off and on. I had a custodian job at a church from 2013 to 2014, and I would clean and listen to Bookworm, otherppl, literary podcasts from The New Yorker. Then, I would go home and read all these writers’ books. There were years where all I did was read. Especially after I got sober. [In 2018,] I had a shitty vending machine job in Montana, and I was by myself, and I would read and drive around listening to audiobooks. I was close to reading 150 books a year, and I started to find some I really connected with.

I read What Would Lynne Tillman Do? during that time. Even though I read some of your other books before that, that was my first real introduction to your work, Lynne. [And then] I traveled for the reading in 2022, and that changed a lot of things. Of course, Lynne, when I was reading with you, I was aware of you and had read your work.

LT: None of which I knew. One of the things that’s interesting about you, Taylor, is that if you weren’t from Indiana, if you were a New York guy, you would have said, “I’ve read all your work, Lynne!”

TL: Is that what I was supposed to do?

LT: You weren’t supposed to do it! It would just be a typical meeting with a younger writer. But you being more circumspect, and more shy, or discreet, or secretive—we could offer many adjectives to talk about this—you didn’t say anything like that.

Nik, after hearing him read his story, which I liked very much—and which, of course, made it possible for us to have a conversation later—I did point out one thing that I thought was a problem. Immediately after he read, I said, “I really liked your story a lot, but I think you need to look at this.” Right, Taylor? Didn’t I do that?

TL: Yep.

LT: Did you mind when I did that?

TL: No. I didn’t care; it was sweet.

LT: Okay. Anyway, afterward, we went to the Odeon, and a whole group of us, including Taylor and I, talked a lot. I still didn’t know that he’d ever read anything I’d ever written. He didn’t say. And then, I don’t know, six months later, he called me, and he said he’d like to interview me. I’ve been interviewed a number of times, so I didn’t think anything of it.

TL: I wanted to do some sort of larger interview with Lynne because I knew that there were so many things that she’d been a part of that I wanted to tie together, and that I didn’t see connected elsewhere. There’s this strange dichotomy between the literary and art worlds that Lynne has been able to go between, existing in both. Thinking about writers in their context and in literary criticism is something I’ve always found exciting and interesting, and I don’t know if I’ve seen that kind of criticism or history done before. At first, I wanted it to be a Paris Review interview, and they said no.

LT: Someone else tried to do a feature about my writing for The New Yorker maybe five or six years ago, and they said I wasn’t famous enough.

TL: So stupid.

LT: Now, I wouldn’t want to do a New Yorker feature. Now that I’ve read more of them, I find them kind of sickening.

Why?

LT: I know some of the people they’re talking to, and I know how invasive these features are. I know how unsatisfying they are to the people who they talk to. I’m sure it gives the writer a lot of publicity, or gets them readers they did not have before, perhaps, but the whole process sounds, to me, very difficult in the way it interferes with your regular life. When you get published, there’s a period of a couple of months, sometimes, or a month at least, where your life is upended by what’s going on.

So, I didn’t realize what kind of interview Taylor was going to do. I didn’t know that he would want to go into my history and ask about literary friends of mine and other friends to some extent, but I don’t talk about many friends in this. Just some who are really related to writing. Then, there was a second interview. By then, Taylor, you were sure you wanted to do a book. And I said, “Okay.” But I don’t believe [that sort of thing is going to happen] until it’s real. And as we went on, it became more real.

I’m also naive in a lot of ways, Nik. [Laughs.] My ability to trust comes from a certain naivete. I usually think people aren’t going to do something terrible to me. (Recently, I discovered that there are some people I shouldn’t have trusted.) Taylor’s desire to do this book with me—I didn’t really fully get what it was going to be.

This book was conducted over the phone?

TL: It’s about 10 hours of raw interview. The first two sessions came from two hours in Lynne’s apartment. The rest was over the phone. I would record the audio, transcribe it, edit it, and compile it into sections, and then Lynne and I shared a Google Doc and started editing it as well.

LT: He was very thorough. He had certain questions and ideas he wanted to talk about, and they were often unlike anyone else’s. And that impressed me, I don’t know what I expected. But this was much more organized, thought through. He really had a mission, I think. To destroy me!

[Laughs.]

I’m just joking. He asked me questions that I resisted, like what do I want my legacy to be?

TL: It’s a unique book—an extended long interview with photos and essays. It’s a record in some ways—of Lynne’s work, but also of how a reader, me, relates to Lynne’s work. And sometimes I went into it thinking, “I don’t know why I connect with Lynne’s work.” I had to kind of discern that while I was doing this.

LT: I think one of the things that’s most peculiar for me, and maybe for many writers who are serious about their writing, is why somebody likes your work. I’m always surprised when someone tells me, “Your writing is important to me.” There is a gap for me. Obviously, I have some belief in my writing. So many books that I have read made a real place in my heart and mind. But when you discover someone else—an other—finds your work meaningful … to me, it’s astonishing.

When you started doing phone calls, what did you think Taylor’s “mission” was?

LT: It is a good question. At first, I remember you asking me some questions that I found so different from the way I experienced things. About legacy, or finding yourself—a self—that Taylor and I disagreed about it. I think that’s part of the conversation that might be interesting to other people. But as it went along, considering the kinds of questions he had, I think he was interested in a writer’s life. Here he is, much younger than I am. I think he wanted to understand how I, a writer who has an unconventional career doing a lot of different kinds of writing, persevered. How I got through it.

Still, it wasn’t career-oriented. It wasn’t, “How did you get your first book published?” It was much more about if he could see me … I don’t want to say as a model, but as a survivor of this literary tradition. Could he see that someone who was not a conventional writer, who was not in the mainstream, who struggled for readers—not that I was in some kind of wrestling match—continued?

It’s very hard to deal with rejection, and very, very hard to go on. I’ve heard this statistic that 80 percent of people who have a first book out never publish again. Somehow, you have to have this sense that what you’re doing is interesting. And I did, even though I had to spend most of my life in psychoanalysis or psychoanalytic psychotherapy to keep me going. (And not just about all the neuroses I had about even showing my work, which took me a long time.) I think Taylor was interested in how I coped. Is that true, do you think, Taylor?

TL: It’s fascinating to hear your perspective. I don’t know how to respond. In some ways, I think you’re correct. I did want to know how you do it and how you did it. I also knew it would be valuable for others. I think the initial idea of the book, beyond my personal reasons, was to connect all these different things you have done and pull them all together as a service to your work.

LT: That’s a very charitable goal. But we don’t talk much about writing, per se. Why I wrote something in this way or that—it’s not that kind of critical analysis. It’s much more about a life.

TL: I agree. We talk a lot about friendships …

LT: Philosophical issues.

TL: I wanted to know how you thought about things and approached life. When we spoke about legacy—a lot of writers don’t have an opportunity to respond to that.

LT: I appreciate it. Not long after all of this, Gary Indiana died. Gary and I often joked about what we’d leave behind and how ridiculous it was because both of us know literary histories where people just disappear. When you die, whether you’re a writer or not, you disappear.

When I was 16 or 17, I wrote an essay about Chaucer’s legacy. Now, why that came into my mind to do … Actually, it was clear to me. I was already very concerned with what happened to the writer, how writers disappeared. I thought I might not get published, or that if I did, I would disappear.

I didn’t realize I would have tremendous emotions about what publishing was. I thought I would be much less vulnerable, having read these books. But reading a book doesn’t protect you.

Protect you from what?

LT: From having feelings. You know, I read about many people who just disappeared. Chaucer did for 200 years. Everybody talks about how Moby-Dick only sold 80 copies upon publication. I thought knowing that was like some armor, but it’s not.

One of the things that really freaks me out—and is probably why I’m a writer—is how quickly a person vanishes. There’s a month, or two, or three of mourning … it makes me want to cry just thinking about it.

TL: Me too.

LT: I’ve known so many people who have died, and when I start thinking about that, I want so much to keep them alive. Somehow—this may be why Freud put together hysteria and writing—to hold on to those people. (A lot of people don’t want to be reminded.) In Thrilled to Death, in my acknowledgments, I include some of the people who’ve died, and dedicate it to my father, who’s been dead a long time. The desire not to forget is huge in me.

TL: This feeling of resisting disappearance … you can’t, obviously, but there is something with capturing consciousness in literature that instills it beyond a person’s human existence. I do feel like sometimes writing, the act of it, is some kind of communing with the dead.

LT: The other night, I went to a Jason Moran concert, who’s a brilliant piano player and jazz composer. Just amazing. And he was playing Duke Ellington and Billy Strayhorn music. It was at the Apollo, so it had all that history, and in the background there were moving slides of photographs by Gordon Parks of Ellington and Strayhorn and Lena Horne. There were “at home” portraits of Duke Ellington lying in bed with four pints of ice cream in front of him. At one point, Jason said that he plays to the spirit of Duke Ellington, and that without Duke Ellington, there wouldn’t have been Thelonious Monk.

The whole history and lineage of writing is also in that. I don’t know if I’m writing to the spirit of Jane Bowles—I hope not, because she would reject [that connection] if she were alive. But I think that, like jazz, where people are responding to music before, whether it’s conscious or unconscious, we are riffing off things from the past.

It’s interesting that you bring up the unconscious. It comes up throughout the book—you correct Taylor from subconscious to unconscious at one point—and is an important element in your novels. I found myself thinking about what unconsciously is coming up in your conversation, again and again, while reading.

TL: That’s the connection I see in this book with Lynne’s work. There’s this fluidity in identity and fluidity in voice that really shows why literature can go to the depths of, yes, the unconscious, but also [how it can help us] understand what makes a person.

LT: I think you’re right, Nik, that the unconscious is always there. In American Genius, A Comedy, I try to make it conscious through these long sentences that wind around and come back to some other point or don’t return to where they should be, but there’s a paradox because, in a sense, the unconscious is always unknowable. Trying to do that, but also knowing you can’t, really, is as close to it as I can get in writing so far.

The narrator in that book keeps a roll of fabric that her father made in her room. That’s from the unconscious, this “fabric monolith.” The way in which I think about my father as always being there. My father designed fabrics and had them manufactured. When I went to his office a couple of times and went into the stockroom, I just loved all the rolls and rolls of fabrics in different colors. There are many ways to interpret that fabric monolith. One is the idea of potential. From this roll of fabric, my father would have shirts made, dresses or blouses. As a child, that was fascinating to me: that this could become that.

TL: There was a moment in our conversation that I found so fascinating, where you [explained how, when you were young, you] watched the 8 mm film of “life before Lynne” in a closet. It felt like you were trying to figure out why you’re different from your sisters. Also, maybe not in that moment, but in the context of our conversation, it felt attached to your father’s loss.

LT: You know what’s funny? No matter how much we look, we don’t necessarily see. When I got the film put onto videotape, about 30 minutes of this family footage, I had my friend Jane Weinstock watch them. She said something that I had never noticed; she said, “What I noticed was you never look at the camera.”

I’m about one and a half or two in the film. My sisters were playing for the camera, smiling and running toward it. My father is shooting this, and I run toward him very happily; I’m not really running toward the camera. I’m running to him.

You mentioned, Taylor, that the book includes photographs from Lynne’s life. Can you speak to your choice to include photography in the book?

LT: I’m ambivalent about having photos. Though I didn’t refuse. I feel quite exposed by the conversations already!

TL: It was really important to me to have a photographic record along with the oral, obviously in terms of Lynne’s own preoccupation as a writer, but also [to create] a better reading experience. I initially spent three days at Fales Library at NYU, going through box after box. After Fales, Lynne provided some photos that were in her apartment or on her Instagram, phone, and computer. I think even just having a postcard and photo of David Rattray in the book is special and corresponds to what we talked about—keeping others alive a little longer.

Alongside those concerns of mortality and legacy, you have a deep interest in the concept of a “true self” throughout the book, particularly in relation to gender, and revisit it after Lynne’s initial resistance to the term. I don’t know if it entirely settles within the length of the conversation; I was wondering if you had any other thoughts on the subject.

TL: We do get to some sort of conclusion: Lynne talks about how she had this goal of wanting to become a writer and there were all these obstacles in place as she moved toward being one. That’s one level of this idea of an authentic self, which I don’t know if I necessarily believe in. I started thinking about [the concept] years ago, because I made a decision that radically changed my life. I don’t think I would be alive right now if I hadn’t made that decision to get sober—and stay sober.

Still, there’s this overwhelming feeling—even now—that I’m not “myself.” That’s how I feel a lot: like, I’m disconnected from who I am. I don’t know if it’s related to gender or mental illness or geography, [being in Indiana,] but it’s a real struggle that I have—feeling rooted or grounded or in my skin.

Some of the only times that I feel rooted are through literature. Reading and writing have always helped me feel more grounded. So, I also feel this obligation to cultivate or add on to what has already been done here in Indiana. I want to create a literary community through the bookstore, and there’s so much here for me to think and write about.

LT: I think, Taylor, we’re all becoming. I don’t think we settle. Because you are not just what you think, but also how you act. You know what you do in your life. The more you do in life, the more settled you become in yourself. There are hypocrites, of course; we know. Many. But I think that alignment between what we think and what we do is important in terms of “knowing thyself,” to the extent one can. There are always things that come up that test your principles.

Do you have any hopes for this book?

TL: I’m excited to sell the book in my bookstore. I’ve probably sold more of Lynne’s books in Indiana than ever before.

LT: People will know better who you are, Taylor.

TL: Yeah, one of my high school students referenced it and wanted to know more about it. I don’t want to jinx it in some weird way; I just hope people read it.

LT: I know you want people to read it. I’m not sure I do.

TL: Why?

LT: It’s very exposing! It’s not something I want to do. I can’t say my books speak for me because they don’t. They speak for something else.

I mean, one of the reasons I did this (and that I do a number of different things)—and let you, Taylor, put pictures in, which you know I’m ambivalent about—is because I want to act against the tendency of women not to be forthcoming. To be worried, as I am, about exposing myself or talking too much, or all of these things that many of us women have been acculturated to. That’s that oppositional side. I’ll do something because I feel that what has been going on is not productive. So, I’m a female guinea pig.

I am grateful to you for this interest. And I’m sure when I’m dead, I’ll really appreciate it. I’ll take it to my grave!

You’ll have to contend with having your first book, Taylor.

LT: He’s hiding behind me.

Well, it’s funny. Taylor, you mentioned in the book that you want the thoughts and sentences of your conversation with Lynne to spiral like those of her more psychoanalytic novels. So, in a way, you have conducted a Lynne Tillman book.

TL: That’s good.

LT: So, Taylor, maybe the question of who you are has been answered. You are Lynne Tillman.

TL: [Laughs.] Perfect.

¤

Lynne Tillman is a novelist, short story writer, and cultural critic. Her novels are Haunted Houses (1987); Motion Sickness (1991); Cast in Doubt (1992); No Lease on Life (1998), a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award in Fiction; American Genius, A Comedy (2006); and Men and Apparitions (2018). Her nonfiction books include The Velvet Years: Warhol’s Factory 1965–1967 (1995), with photographs by Stephen Shore; Bookstore: The Life and Times of Jeannette Watson and Books & Co. (1999); and What Would Lynne Tillman Do? (2013), a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award in Criticism. She is the recipient of a Guggenheim Foundation Fellowship and the Andy Warhol Foundation Arts Writers Grant. Tillman is a professor and writer in residence in the Department of English at the University of Albany, and lives in New York with bass player David Hofstra.

Taylor Lewandowski has written for Interview Magazine, Bookforum, Los Angeles Review of Books, Forever Magazine, and The Creative Independent, among other publications. He owns Dream Palace Books & Coffee and lives in Indianapolis.

LARB Contributor

Nik Slackman is a writer from New Jersey. He works at Fence, where he served as managing editor for The One on Earth: Selected Works of Mark Baumer (2021), and has recently published interviews and fiction in the Cleveland Review of Books, Recliner, and Blue Arrangements.

Share

LARB Staff Recommendations

-

Lynne Tillman talks about her friendship with the late art critic, Craig Owens.

-

In “Men and Apparitions,” she seesaws between an analysis of physical pictures and an examination of the ways we picture ourselves and others.

Get first dibs on exclusive art from Dave Eggers

Featuring “Incorrectly,” “Nice,” “I Love the Night Life,” and more, select prints from the collection are now available in our shop. Become a LARB member to shop the prints before they are gone!