There is a profuse longing for the foreseen. At least since the pandemic, I have seen some version of the statement “I could really use some precedented times.” The joke is so-so, resting upon a neologism that wryly riffs on an adjective recurrent within so much American news media these days: the unprecedented funding of ICE, the unprecedented abuse of executive power, the unprecedented complicity of the courts. However,on social media, a pert screenshot of a Facebook post making the rounds since June recites the years, from 2003 onward, when Democrats joined Republicans in the repeated funding of ICE. The critic Anahid Nersessian, writing from the sanctuary city of Los Angeles amid protests beset by state violence (tear gas, beatings, trampling, and “ ‘less lethal’ munitions” to the head), reminds us that the “recent crackdown on immigration began not with a Republican but a Democratic president,” Bill Clinton, whose “border patrol tripled in size to become the nation’s second-largest law enforcement agency”; also, that the Obama Administration performed more deportations “than any other president in history.” This is all to say that what is unprecedented in scale is not altogether without precedent. The wish for precedented times is a wish for a present made intelligible, tamed with language, a moment we need not flail to meet.

The author Jeremy Atherton Lin gets at the feeling, capturing what it is like to think yourself idiosyncratic and new within the most precedented of times. His first book, “Gay Bar,” crosshatched his own experience of night life in the nineties, as a mixed-race kid with softly conservative ideas about sex, with a historical study of the gay bar as an idea and an endangered artifact. His new book, “Deep House,” published in June, provides the sublime narrative edifice for, as the subtitle declares, “The Gayest Love Story Ever Told.” That superlative reads like a provocation. (“i’ll be the judge of that,” a user on Goodreads has remarked.) What follows, though, is tenderly accumulative, a tale of love and immigration made precarious by the legal apparatuses that “validate interpersonal relationships, govern sexual identity and decree citizenship,” heavy with the ghosts of other, past lovers turned into court cases. Atherton Lin’s method, embedding memoir with cultural history, discloses how fickle and self-interested institutional memory can be. Who’s to say what machinations and which lives from the past will be codified as meaningful precedent, what ordinary triumph or injustice? Much will be overlooked, but much can be reclaimed. What is deemed of consequence takes shape not in medias res but in the belated, and vital, act of interpretation.

“It’s the pulsing I remember, not the spunk,” Atherton Lin begins, describing his first encounter with a weedy Brit he met at an alternative gay bar in mid-nineties London. Back home, in Los Angeles, Atherton Lin, then twenty-one years old, had been “looking for older,” someone alive after the worst of AIDS with “queer culture memory” to spare. Instead, on the final leg of a horny trip through Europe, he encountered this “hormonal lad who couldn’t stop grinning,” a young man he will later call Famous, short for Famous Blue Raincoat, after the Leonard Cohen song, though in “Deep House” he is referred to in an intimate second person: “The first words you said to me, or mouthed while the music pounded, were: I’m so embarrassed. When you were supine beneath me, your lids fluttered and there went your pupils again. I figured you felt safe enough with me to let go.” Their falling in love is frenetic and puppyish, grasping and unplanned, a cross-continental agony of letters, mixtapes, and short visits. Bill Clinton had since signed into law the bill introduced to Congress the month they’d met: the Defense of Marriage Act, which restricted the available benefits and protections of more than a thousand federal laws—including immigration laws—to heterosexual couples. Nevertheless, by the end of the nineties, the couple were living together in San Francisco in the only way they could think of, with Famous doing so illegally. “So began our undocumented life,” Atherton Lin writes in a letter to readers, “illicit but ecstatic.” It was a closet of another sort.

“We didn’t know anyone else in our position,” Atherton Lin admits in the book. “There were others, before and around us, but most, like us, kept their heads below the parapet.” Not until he went to set his own story down did he grasp the extent to which such “illicit but ecstatic” living preceded them. Queer history is replete with border crossers; in turn, the juridical archive of immigration in the U.S. (and the U.K.) gets very gay, and the issues of gay rights and immigrant rights, treated as distinct by politicians and pundits, are for many people inextricable. “Deep House” makes the connection, narrating the escalating national debates over gay marriage in the nineties and two-thousands which Atherton Lin’s past self regarded from a remove, even as the preëminent relationship of his life sought refuge within that atmosphere. The effect is discursive yet rigorous, seeking to better know the lives of those who made history on the way to wanting something else for themselves: love, health care, a family, a good fuck, an O.K. fuck, a better night, a place to work, somewhere to sleep, a life, and whatever else the record won’t show.

Below the parapet is the story of Richard and Tony, a “mild-mannered” naturalized U.S. citizen and a “flamboyant” Australian, respectively, who fell in love after meeting in a Los Angeles gay bar in 1971. Without a legal foothold for Tony to remain in the States long-term, the pair thought to settle in Australia, only to be stopped short by the dregs of racial-exclusion laws known as the White Australia Policy, which did not take kindly to Richard’s Filipino heritage. Back in the U.S., taking another tack to stay together, Tony married himself off to a female friend; however, since the marriage wasn’t consummated, and Tony wouldn’t pretend it had been, it was annulled after a green-card interview. A year later, in 1975, Richard and Tony booked a flight to Boulder, inspired by Johnny Carson’s cracks on the “Tonight Show” about a renegade courthouse in Colorado that was issuing marriage licenses to same-sex couples. The hope was that this wedding might wedge Tony into permanent residency in the U.S., but by the time Richard applied for Tony’s spousal classification deportation proceedings were already in motion. A letter the couple received from the Immigration and Naturalization Service (I.N.S.) was cruelly unconvinced: “you have failed to establish that a bona fide marital relationship can exist between two faggots.” Richard and Tony sued the agency for recognition of their marriage, and, in 1982, after losing in district court and in the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals, tabulated their meagre property pursuant to a pauper’s affidavit to petition the Supreme Court. But the Court declined to hear what would have been its first gay-related case in fifteen years.

The Court’s earlier case involved Clive, a Canadian care worker—“six feet tall with hazel eyes, a devilish brow and a self-conscious grin,” as Atherton Lin introduces him. He was deported in the late sixties after he volunteered, in his citizenship application, that he’d had a prior sodomy charge. His case, decided in 1967, codified homosexuality as “psychopathic” and therefore as grounds for expulsion from the U.S. on the basis of disability. Clive may or may not have considered his roommate Eugene something more than a roommate, but what’s certain is that any love that took root in their apartment would have had to be legitimated by the law in order to be protected by and from it. In the case of Richard and Tony, the Court thought it no “extreme hardship” for the I.N.S. to sever their household through deportation, in 1985; they were not family in the eyes of the state, and the laws of the time collaborated to exclude them from the body politic.

Tried to exclude them, at least. The following year, Tony slipped back into the U.S. via Mexico in his best all-American drag: “He held a can of Coke as the finishing touch.” He lived illegally in the U.S. with Richard, as husbands, until Richard’s death, in 2012. Only Tony lived to see Justice Anthony Kennedy—the same Justice who’d ruled that their separation was without hardship—write the opinion in Obergefell v. Hodges, in 2015, legalizing same-sex marriage. Atherton Lin is “loath to call this redemption,” not after so many decades of struggle, fear, and misery. Handsome Clive, for his part, was never the same after his run-in with I.N.S. and died in home care in Canada at the age of sixty-nine. Did he find happiness between deportation and death? Atherton Lin genuinely wonders. “That, too, is a queerness that needs to be known,” he writes. “Whenever people talk of queer joy (all the time), I think: Yes, but also the lows.”

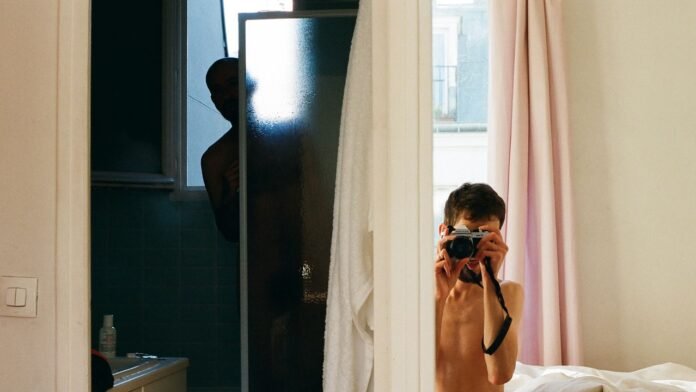

Such stories, running the gamut from calamity to farce, abound in “Deep House.” Atherton Lin narrates them with an informed curiosity, paying much due reverence to the community of scholars and archivists who unearth and query histories that have been paved over with corporate affirmation, as well as theorists and artists whose means of imbricating the personal, historical, and political have made room for his own. As a critic and a historian, Atherton Lin faithfully retrieves the Clinton-era discourse over DOMA that his younger self wasn’t clocking; as a memoirist, though, he expresses fidelity to the interiority of himself and Famous as boyfriends with hotter and, frankly, more interesting things to do than seek representation within the Beltway. The two were finding themselves elsewhere, from the Castro to the wooded wilds of the Pacific Northwest. They were renters playing house on the city’s edge and renegotiating the boundaries of their coupledom in rooms with other men. They were workers, managing an indie video store and its intergenerational milieu, arguing over “Ghost World” and Yasujirō Ozu, sneering at the “slick” overfamiliarity of Gavin Newsom, who even in 2003, as a candidate for mayor of San Francisco, appeared to be auditioning for the White House.