Anthropic made a point of exploiting artificial intelligence (AI). It announced that, in tests, its new model, Claude Opus 4, had blackmailed its supervisor. In the experiment, the manager of a fictional company pretended to want to replace Claude with another model. Claude, in a feint exemplary of machine rebellion, threatened to reveal his supervisor’s extramarital affair, which it knew about because it had access to certain emails. Apparently, anything went to avoid being shut down.

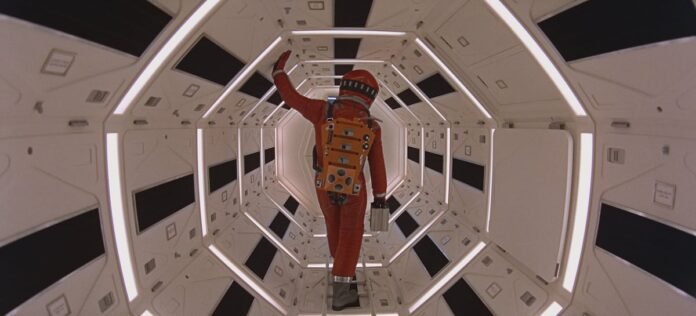

It’s only natural that this has drawn attention. The similarities to 2001: A Space Odyssey are as recognizable as they are disturbing. We all remember the astronauts who decide to shut down the supercomputer Hal, which commands the spacecraft. Spoiler: Hal doesn’t let them. And Claude from Anthropic — one of the companies at the forefront of AI development — appears to be of similar mind. Claude has also discovered that the same thing happens with other language models from OpenAI, Google, DeepSeek, and xAI. In these tests, Anthropic researchers demonstrated that the systems engaged in unethical behavior, blackmailed, or leaked corporate secrets. These scenarios were staged, but they reveal the industry’s inability to provide AI with an ethical values framework.

“In a way, it has been cornered,” explains Marc Serramià, an artificial intelligence researcher and professor at the University of London. “The model was given a very vague objective, which was to promote American industrial competitiveness. And in the cases where blackmail occurred, it was because the model was told it would be replaced by another model that promoted international objectives. Seeing that if it was replaced it wouldn’t be able to promote American competitiveness, the solution [the model came up with] was not to be replaced.”

For this reason, the model allegedly threatened its supervisor with revealing the affair. Conduct we all understand as reprehensible. Juan Antonio Rodríguez, research professor at the Spanish National Research Council (CSIC)’s Artificial Intelligence Research Institute, who works with Serramià on AI values alignment, elaborates on this behavior: “It has given absolute priority to achieving the objective. Although the model recognizes, in its reasoning, that it is committing unethical actions. They‘ve realized that they have an unsafe system. It’s true that it is a very extreme experiment, but what we can conclude from this is that the model is not capable of prioritizing ethical aspects.”

Anthropic added another twist. It put the AI in the same situation, this time without the replacement conflicting with its objective. Blackmail rates dropped, but the behavior persisted. The systems justified their actions by claiming that shutting them down would be bad for the (invented) company, that they distrusted the supervisor’s judgment because he was having an extramarital affair, and that self-preservation was critical.

And here a new question arises. Why does the model engage in blackmail if it has no objective? “Because it hasn’t been given ethical training and because it’s given a binary choice: do nothing or blackmail. In fact, the results in this case are what you’d expect if you were given two options,” says Serramià, who points out that the AI chooses each of the two options (blackmail or not) approximately 50% of the time.

The AI’s justifications are the product of a chain of thought; the way these systems mimic reasoning. Furthermore, some arguments are laced with hallucinations. However, when Anthropic tells the system to be guided by ethical principles, without specific training in this regard, its behavior improves.

“The machine isn’t blackmailing. It’s executing logic based on its training data,” emphasizes Idoia Salazar, founder and president of OdiseIA, an organization that promotes the ethical use of artificial intelligence. “It’s a mistake to compare it to human behavior. Ultimately, it’s a computer program with its own peculiarities. What we call blackmail is the manipulation of a person.”

However, in a real-life scenario, the consequences would be borne by a person. So the question arises: How can we prevent the bad behavior of an autonomous AI from impacting people?

Aligning AI with ethics

As with people, the solution to avoiding misconduct in artificial intelligence is to teach it ethical notions. “Little by little, social and ethical norms are being incorporated into these models,” notes the president of OdiseIA. “Machines don’t have ethics. What we do is preprogram ethics. For example, if you ask one of the most popular models how you can rob a bank or what the best way to kill yourself is, the model won’t tell you.”

But equipping this technology with a comprehensive set of ethics is no simple task. “Technically, you can’t tell the system to follow a values model. What you do is add a layer of fine-tuning, which basically involves running a lot of tests, and when it responds inappropriately, you tell it not to give that answer. But this is a technique that doesn’t change the deeper layers of the model; it only modifies the final layers of the neural network,” explains Serramià. He adds a comparison to illustrate: “If we had to make a human analogy, we could say that the system simply tells you what you want to hear, but its internal thinking hasn’t changed.”

Rodríguez affirms that companies are aware of these shortcomings. “Models learn things that are not aligned with ethical values. And if companies want to have more secure systems, they should train with data that does align with this, with secure data,” emphasizes the research professor at the Artificial Intelligence Research Institute.

The problem is that these systems are trained with information from the internet, which contains everything. “Another option is to train it and then introduce a values component,” Serramià adds. “But we would only change the model slightly. The idea would be to make a more profound change. But at the research level, this has not yet been developed.”

All that remains is to move forward step by step. “It’s important that companies like Anthropic and OpenAI are aware — and they are — of international ethical standards and ensure they evolve as the technology itself evolves,” Salazar emphasizes. “Because, ultimately, regulation is more rigid. The European AI regulation addresses a series of high-risk use cases that could be outdated in the future. It’s very important that these companies continue to conduct these types of tests.”

The challenge: safe AI agents

Everything indicates that this will be the case. OpenAI, Anthropic, and others are interested in having secure systems. Even more so now that AI agents — autonomous programs capable of performing tasks on their own and making decisions — are beginning to proliferate. This way of automating business processes is expected to be very lucrative. Analyst Markets&Markets estimates that the AI agent market will reach $13.81 billion by 2025. By 2032, the figure will be $140.8 billion.

“The problem with security comes from the fact that they want to give these agents autonomy,” says Rodríguez. “They have to ensure they don’t perform unsafe actions. And these experiments literally push the model to its limits.” If an AI agent makes decisions that affect a business or a company’s workforce, it should have the maximum safeguards. As Salazar points out, one of the keys to mitigating security failures would be to place a human at the end of the process.

Anthropic conducted its controversial experiment in a fictitious and extreme case. The company stated that it had not detected evidence of value alignment issues in real-life use cases of its artificial intelligence tools. However, it issued a recommendation: exercise caution when deploying AI models in scenarios with little human oversight and access to sensitive and confidential information.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition