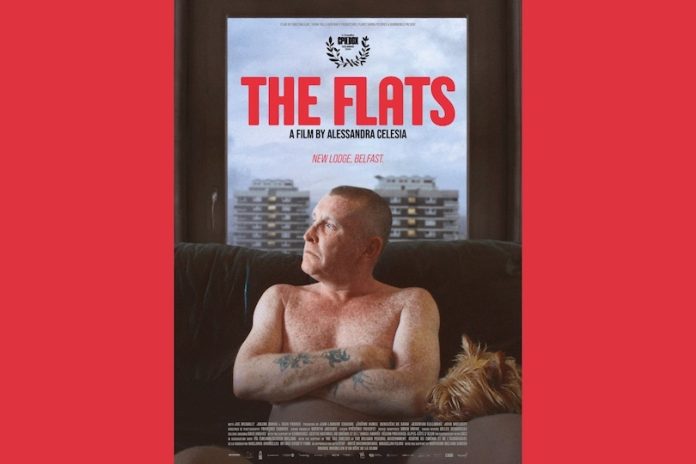

The Flats

Directed by Alessandra Celesia, 2024; Thank you and good night productions (Belgium), Planet Korda (Republic of Ireland) and Dumbworld (UK)

Starring Jolene Burns, Joe McNally, and Sean Parker, The Flats by Alessandra Celesia is a formidably grim portrayal of high-rise life Belfast – “New Lodge style” – in a drama which jumps from the 1970s to the present (and back again) in a cinemographic instant. It adds to the repertoire of “real-life” documentary dramas of interest to IR students and aficionados of political conflicts the world over. As for plot, in his tower-block apartment in New Lodge, Joe reenacts memories from his childhood amidst the “Troubles”. In this Catholic area of Belfast, the number of 1970s deaths seemed haemorrhagic. Joe is joined by neighbours Jolene, Sean, Angie, and others, all willingly participating in this process of revisiting the collective memories of the New Lodge district they share (and perhaps even begrudgingly love). It is a frank and at times emotionally cathartic experience for actors and audience alike.

For those not familiar with Belfast and its much euphemized “troubles”, New Lodge comprised seven 12-storey towers in its urbanized heart. It was one of the areas most severely affected by conflict during three decades. It was a district where the number of casualties per inhabitant still shocks an international public. Today, this small Catholic neighbourhood is marked by urban and industrial obsolesce and social abandonment. Yet, something like an idealism and black humour percolates, emanating from the undoubted humanity and caustic humour of its inhabitants. That expert film reviewers approve enthusiastically of this effort by Celestia and her colleagues is shown by its crop of successes at recent festivals – having already won the CPH:DOX and the Visions du Réel, among others. This is also evidence that Northern Ireland continues to rate high on the agenda of the global film-going public.

Anatomy of a Conflict

What is new about this film which might help us understand the conflict? Essentially this neglected Belfast housing estate offers a haunted inner landscape with dark, cinematic echoes that still reverberate in the very corridors of the aged New Lodge flats. An aging man on his final, existential mission confronts the ghosts of the past. In Alessandra Celesia words: “My aim was not to make a ‘political’ film, you know, but just to see the consequences of trauma… I thought, if we could get to the bottom of that, maybe it could represent the long-term consequences of many other wars as well.” The film shows the lead-actor (Joe McNally) struggling to drag a coffin into his run-down apartment block. It is almost an apocalyptic scene except this is a Belfast which has experienced thousands of deaths, and people are all but nostalgic about the bad old days. Undoubtedly, ‘The Flats’ offers a haunted interior landscape where past and present merge. It is conflict nostalgia and it is sometimes unclear whether one should laugh or cry, or both. This reader is unequivocal that the film succeeds in arousing both humour and concern in equal measure.

For all this “troubles” nostalgia, New Lodge is still haunted by a conflict which officially ended in 1998. We see Joe’s doppelganger, re-materialized as a child rioter, and then again as an adult. Now almost entombed in “The Flats”, we become eavesdroppers to his conversations with his psychologist, as he ventilates about the ghosts of a horrific past. “I threw my first petrol bomb when I was nine-and-a-half,” he tells Rita Overend, a therapist working for the PIPS Suicide Prevention charity within the community; and we learn how he helped torch a hijacked lorry as a child.

We are told about his teenage uncle – tragically murdered by a sectarian death squad. He talks about the brutal street fights; the unconceivable pain of the hunger strikes and the loss of resistance icon, Bobby Sands. Belfast’s painful modern history is tightly interwoven with the lives of Joe and the other New Lodge residents unfolding in a (seemingly) timeless vacuum that resembles the early years of the 1970s troubles, but is painfully contemporary. With reconstructions and a brilliant use of archival footage, Celesia conjures up for us a highly subjective past like a record placed on continuous repeat. It is like we are lost in “conflict space”.

Celesia’s movie is an amalgam of séance and documentary about the run-down New Lodge estate in what the BBC news used to call “Catholic west Belfast”. It is primarily about families enduring unresolved agony nearly thirty years later. We are witnesses to the psychic residue of political violence; sex, domestic and substance abuse – and a futile rage against drug gangs. Along with reportage of the Queen’s death we learn that the Catholic community in Northern Ireland now outnumbers the Protestant. It is like the end of one era and the birth of another. There are hints of a messianic United Ireland, and perhaps this is the hope that offers this (otherwise) depressed community its resilience. In many ways the movie offers a tragi-comic depiction of the perennial themes of “troubles research” and this makes it invaluable for IR readers.

Dissecting “Troubles Nostalgia”

At the film’s centre, Celesia shows the workaday grind of Joe McNally, an ageing republican still traumatised by his uncle’s murder at the hands of loyalists. He has a despairing sectarian thirst for revenge. Celesia, perhaps emulating Joshua Oppenheimer’s The Act of Killing, encourages Joe to stage a reconstruction of his uncle’s wake. Joe and a friend carry a coffin into his flat for this psychodrama. But far from exorcising Joe’s unquiet spirits, it worsens them. Here the accompanying filmography (using scarcely previously shown reels of conflict scenes) is disturbing. However, the rareness of the footage, and its specificity to west Belfast zones of conflict trauma, provide an authentic filmographic tone to what is otherwise a quite unrestrained docu-drama. The continuous referencing to contemporaneous news footage adds credibility to the artistic licence proffered by the actors in this re-creation of Belfast life.

This is a highly personal film and the ethnographic lens will be of value to all those seeking to understand the human impact of the conflict. Joe talks to his therapist about his memories of the Bobby Sands funeral (and is awestruck at her revelation that she attended Sands’s wake as a little girl). Perhaps inevitably, the coffin that was used to recreate his uncle’s wake is now repurposed to stage something similar for Sands; Joe climbs into the coffin to imagine what death will feel like. When he rages about beginning a hunger strike of his own to publicise the problem with drug dealers in his block of flats, he berates the Provisional IRA who in his view did not care about the possibility of all this happening – and letting his district, as he puts it, become “like Dublin”. By this he means the urban desolation and drug wars which blight certain working-class districts of the Irish capital. It’s an analogy which, to say the least of it, shows an unsentimental view of a United Ireland.

A Tale of Urban Resilience

There is evidence also of personal struggle and the process of “moving on”. Having struggled with criminality, drinking and drugs, the Joe we meet in The Flats is now vehemently anti-drugs. We see him angrily videoing local dealers on his phone (to discourage them.) He is cautioned against his plan to emulate his hero, Bobby Sands, by staging a hunger strike until something is done about them. Although not a father himself, Joe speaks of his fears for the youngsters on the estate: kids like Sean Parker, who portrays the dumbfounded young Joe during a staged recreation of his uncle’s wake, a scene also featuring Joe’s neighbours, Jolene Burns and Angie B Campbell – friends bonded by their shared experiences of domestic violence, whose lives Celesia also documents in the film.

Equally, there is a sense of resilience and survival. Meanwhile a younger woman – a talented singer – is still dealing with her own memories of abuse and Celesia gets her to recreate her victimhood, fabricating the bruises on her face with makeup. One imagines this is a less than subtle reference to the spectre of sexual abuse which haunts the republican community. “So relaxing,” she says, “so much better than a real punch.” And her mum recreates the time she shot her abusive husband in the hip with an IRA revolver.

How may we summarise this production so it is most easily digested and utilized by IR audiences? First, it must be understood that there is a clever interspersing of newsreels and dramatic re-creation. The IR reader must recognize that Celesia is magnifying a number of selective happenings as exemplars of conflict legacy. From reel footage the film turns to staged drama. The wake scene is one of quite a few memorable staged scenes in The Flats, where the director, whose husband’s family has north Belfast roots, was able to call upon her background in theatre in order to visually recreate key moments from her subjects’ lives. This will help IR readers immerse themselves in the lived experiences of Belfast residents so that their lives become more than the flickery footage of TV reports.

When watching The Flats, it quickly becomes apparent that Joe, Jolene and Angie (who has sadly passed away) must have trusted the director completely, granting her intimate access to their lives and allowing the camera to capture them at their most vulnerable. According to Celesia, whose previous documentaries include 2017′s Anatomia del Miracolo and The Belfast Bookseller (2011, also featuring Jolene Burns), the residents at first reluctantly, then enthusiastically, embrace personal story-telling. This film will both educate and fascinate IR students. It offers us a unique view of the conflict as realized in a domestic setting. If we are ever to truly understand those years of conflict it must surely be by appreciating that even the biggest, most televised events, were most profoundly felt by people in their own homes.

Further Reading on E-International Relations