A tour of oil and gas sites encroaching on Denver’s eastern suburbs fell on a fitting day, with air so polluted that state health officials warned the elderly and children to stay inside. Participants were eager to see where these toxic gases come from.

The group stood on the shoulder of a noisy frontage road with a panoramic view of operations that encompass the fossil fuel production lifecycle — the oil storage tanks, a compressor station and a drilling rig spread out on arid grasslands and emitting pollutants including nitrogen oxides and volatile organic compounds.

The gases react when heated by sunlight to create ground-level ozone. Inhaling the pollutant can exacerbate and contribute to the development of lung diseases such as asthma, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

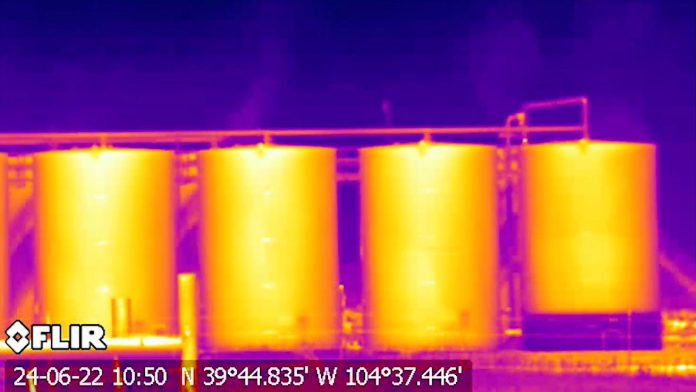

Methane, a colorless, odorless, heat-trapping molecule with 80 times the warming power of carbon dioxide during its first 20 years in the atmosphere, can also leach from equipment on the sites about eight miles south of Denver International Airport. These gases are invisible to the naked eye.

Not today.

Pollutants spewing out of tanks and other equipment on the sites materialized for the half-dozen tour participants in the lens of an optical gas imaging camera perched on a heavy-duty tripod nestled in the road’s shoulder amid broken glass and litter.

Technology inside the device reveals planet-warming hydrocarbons that are absorbing infrared radiation. The bright-blue plume streams out of oilfield equipment into the air against a multicolored landscape.

“Oh, wow,” public health graduate student Natalie Hawley said, as she pulled the brim of her baseball hat low over the viewfinder to block the vicious June sun. “I had no idea these sites are allowed to pollute as much as they do.”

Hawley is among dozens of people who have joined Andrew Klooster, a thermographer at Earthworks, and organizers with 350 Colorado — both environmental nonprofits — on emissions tours at fossil fuel sites since early 2023. Earthworks purchased what’s known as an OGI camera a decade ago with the intent of partnering with residents to watchdog the expanding extraction activities in Colorado.

Earthworks and 350 Colorado teamed up to offer the field trips to alert and educate communities about the health and environmental impacts of oil and gas operations, which continue to grow in the state. The number of active wells in the nation’s fourth-largest oil producing state grew to 46,591 as of Feb. 24, a 25% hike since 2009.

Earthworks and 350 Colorado teamed up to offer the field trips to alert and educate communities about the health and environmental impacts of oil and gas operations, which continue to grow in the state. The number of active wells in the nation’s fourth-largest oil producing state grew to 46,591 as of Feb. 24, a 25% hike since 2009.

The increase in production was fueled by a drilling technique known as fracking, which forces sand and chemicals down a pipe to free fossil fuels trapped miles underground in shale formations. As drilling rigs bristled near the expanding suburbs in the Denver metropolitan area, Earthworks’ mission to empower residents to hold energy companies accountable for the pollution they produce became ever more relevant.

It’s an opportunity “to educate people to be better advocates,” Klooster said. “The air permitting world — what is permissible and what isn’t, and what is a compliance issue — it’s way too complicated for the individual person to parse.”

Emissions from oil and gas sites comprise about 36% of the 253 tons per day of volatile organic compounds released in the region’s atmosphere, according to estimates from the Regional Air Quality Council.

As the quality of air most Coloradans breathe has deteriorated over the last 15 years, a haze began obscuring the view from Denver of the towering Rocky Mountains in the summer. The worsening smog prompted officials to dub May 31 to Aug. 31 “ozone season.” The region’s air is now so bad that state regulators issued air quality alerts for half of the days in that period in 2024.

With Colorado’s population growing in tandem with operations in some of the nation’s most profitable oil and gas fields, traffic and the energy industry have become the main drivers of the nine-county area’s failure to meet federal air quality standards for the last two decades.

For the group standing alongside the frontage road on that hot, smoggy summer day, Klooster explained how he filed a complaint with state air quality regulators about one site visible on the horizon that he visited the day before the tour.

“There was a ton of emissions coming off of that drilling rig yesterday for about a half an hour while I was filming it and I couldn’t identify the exact source,” he said, adding there are limitations to what his $100,000 camera can document.

It cannot help him identify which chemical compounds are being emitted, or how much of them is venting into the atmosphere, he added. However, he can use the videos as evidence to prompt state regulators to investigate.

Documenting where the emissions came from on the drilling rig site was made more difficult because various types of equipment were used on the site on a temporary basis, the thermographer told tour participants.

Civitas Resources, said it sent an inspector to the site three days after Klooster filed his report and that “the drilling rig had completed its operation and started to break down and be removed from the facility. At this point no emissions were observed.”

Civitas Resources, said it sent an inspector to the site three days after Klooster filed his report and that “the drilling rig had completed its operation and started to break down and be removed from the facility. At this point no emissions were observed.”

This story was originally published by Capital & Main and is part of Covering Climate Now, a global journalism collaboration strengthening coverage of the climate story.