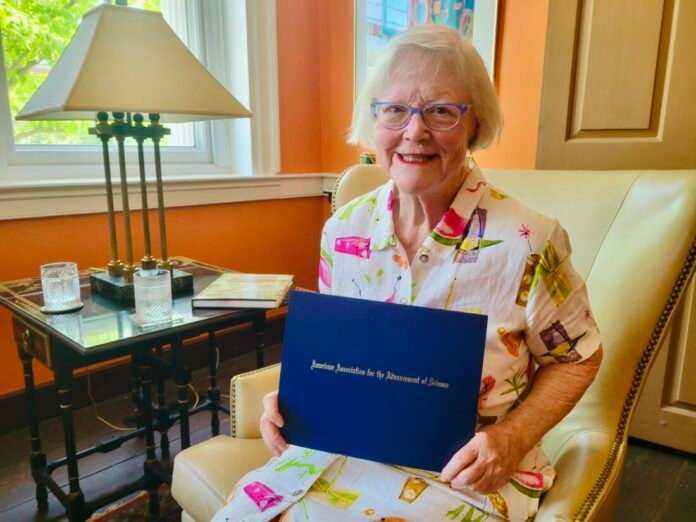

Former NSF Chemical, Bioengineering, Environmental and Transport System Division Deputy Director Sue Kemnitzer Sue Kemnitzer holds her American Association for the Advancement of Science Fellow certificate in her Shepherdstown home. Photo by Tabitha Johnston

SHEPHERDSTOWN — Fifty-five percent is the amount that the National Science Foundation (NSF) may lose in funding, if the federal government’s proposed budget for fiscal year 2026 is approved. Already, the organization has had to terminate roughly 380 grants this year, due to federal funding issues.

For former NSF Chemical, Bioengineering, Environmental and Transport System Division Deputy Director Sue Kemnitzer, these cuts are of great concern. Over the 40 years she worked for NSF, she supported thousands of young scientists who were seeking grant funding to begin making scientific breakthroughs.

“It’s very competitive. The National Science Foundation only funds about five percent of the proposals that they get,” Kemnitzer, who was in charge of $400 million in new grants every year, said. “The job of a person like me, was to help the scientists and engineers in a field submit really good proposals, so that they could get funded. I couldn’t just hand out money to someone — they had to submit a really good proposal, which went through a rigorous review process. I very much took seriously that role, of encouraging especially younger faculty, to submit proposals.”

Through NSF grant funding, Google was established; standards for college engineering program accreditation were broadened to include the teaching of important skills like teamwork, business savvy and the manufacturability of new products; and STEM (science, technology, engineering and math) educational programming was created, such as “PBS News Hour,” “Science Wednesdays” and children’s television shows like, “The Magic School Bus” and “Bill Nye the Science Guy.”

“The National Science Foundation is the gold standard for the world, of an agency that supports science, in particularly, because we have such a robust review process of proposals and we’re so open to new ideas and new directions for science,” Kemnitzer said. “Because of this, other countries want to know how we do this.”

During sabbaticals from her job, Kemnitzer addressed this desire by developing the Partnership for Growth program. The program, which has now been adopted by the U.S. Department of State, was founded in Japan and then continued to grow in Italy, through her dedicated work.

She also founded a number of programs while actively working for the NSF, including: NSF’s first programs for research into how students learn engineering and how these research findings could be translated into practice, new programs to attract veterans to study engineering using the post-9/11 GI bill and the NSF I-Corps program which develops entrepreneurial knowledge and skills in engineering students and faculty. For these accomplishments, she was made a fellow of the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, the American Society for Engineering Education and, this spring, the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS).

“It was all a surprise,” Kemnitzer said of her recent honor by AAAS, which publishes the peer-reviewed academic journal, Science. “Four people who are Fellows must nominate you, for you to be considered to be made a Fellow. To know that your peers feel that you deserve to be honored in this way is wonderful.”

But looking back to the beginning of her career, Kemnitzer said it was heavily influenced by funding issues in the scientific community. While studying science and engineering at the University of California, Los Angeles, the governor of California at the time cut funding at the university in half, which eliminated a number of scientific research positions. She determined she would have a more secure future if she pursued a career in the administrative side of science and, for this reason, changed her career goals and enrolled at George Washington University to earn a master’s degree in science policy.

She worries that, with the significant federal funding cuts to the science field, future scientific developments will be greatly hampered, as many promising students may choose to pursue a more stable career path than what is currently available in the field.

“The biggest thing that I worry about, is that young people will not choose to do science and engineering, because of seeing the cutbacks. They won’t see a future for themselves in those fields. These are very smart people who want to be successful in what they do,” Kemnitzer said. “We need to be sure that we have a cadre of young people coming up through the education system, to be scientists and engineers and, I will also say, doctors and nurses, because those fields require a strong science background.

“Science contributes to our health and economic activity and also stimulates our intellectual curiosity. All of these things are really good outcomes of pursuing science,” Kemnitzer said. “What a wonderful career science and engineering can give you.”