Visual chronicle gives a fascinating and colorful insight into China’s alluring past, Yang Yang reports.

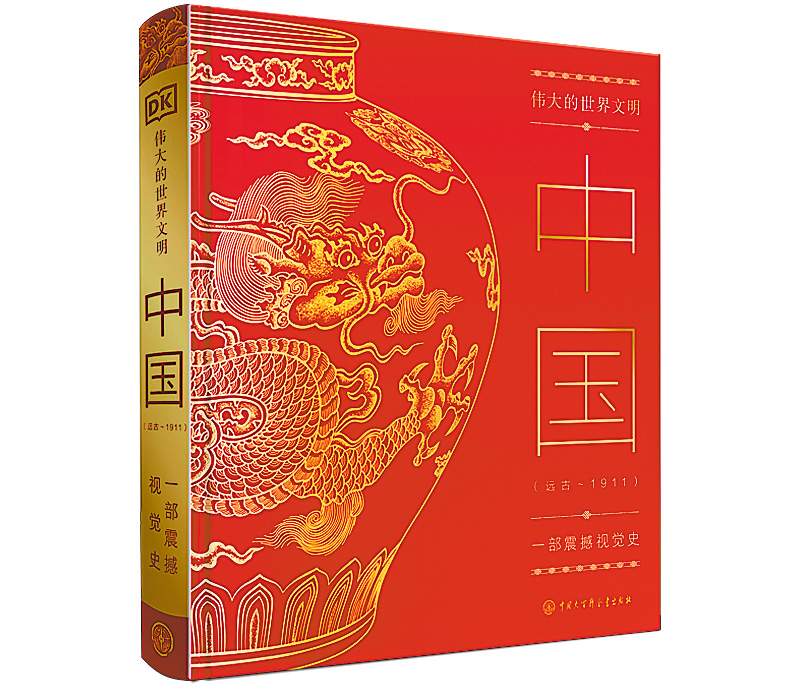

It is impossible not to reach for superlatives when describing China. Global economic power, huge landmass, fascinating history, captivating culture. And a sense that its time has come again. Imperial China: The Definitive Visual History has stunning imagery and photography gracing its well-written and informative pages.

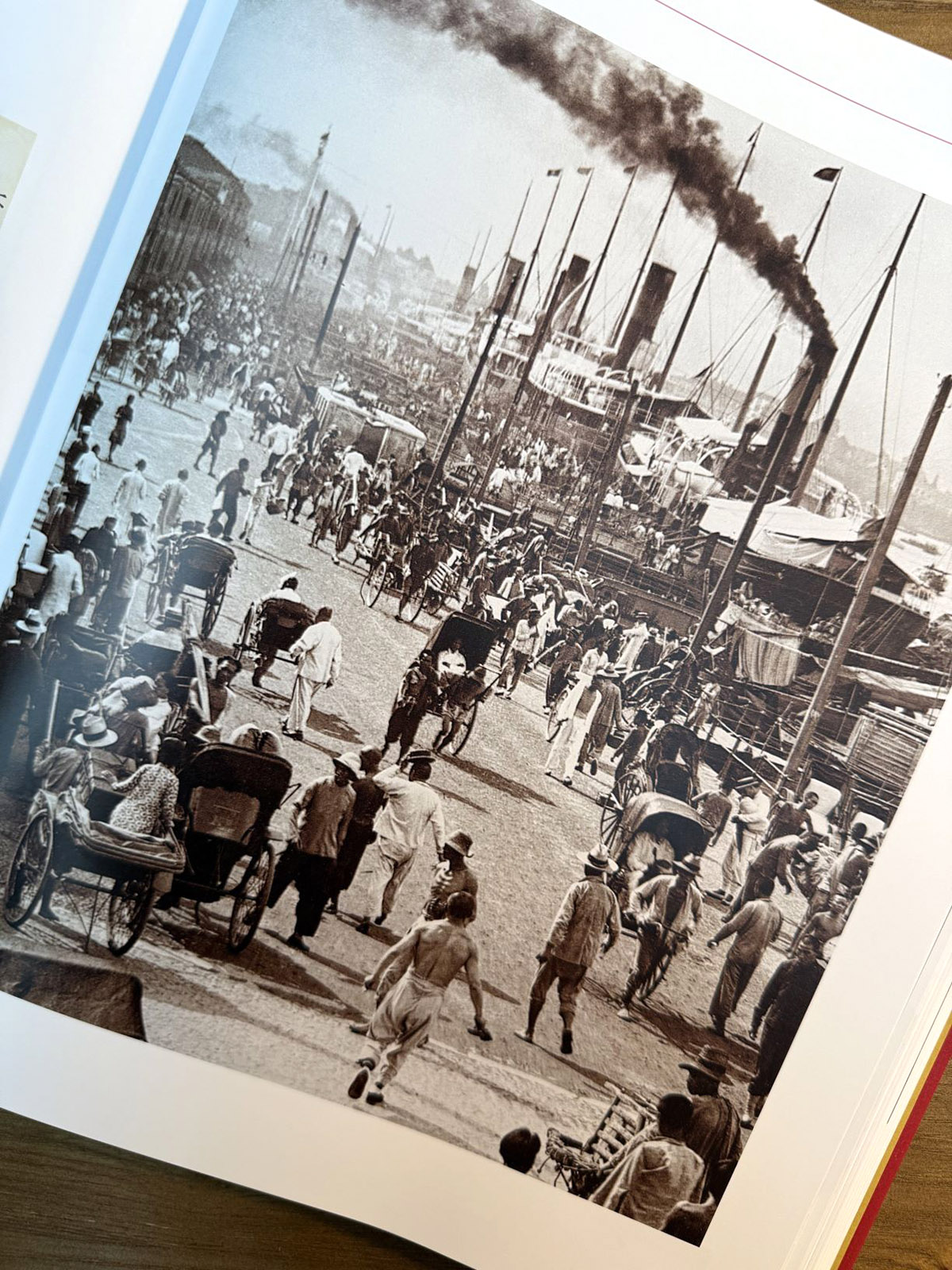

No mean feat to cover so elegantly the span from the clans and legends of prehistory, the governance strategies of the Tang (618-907) and Song (960-1279) dynasties, the evolution of Chinese characters and currency, the cultural significance of the Great Wall or the rise of Confucianism, to the fall of the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911).

READ MORE: Echoes from civilizations

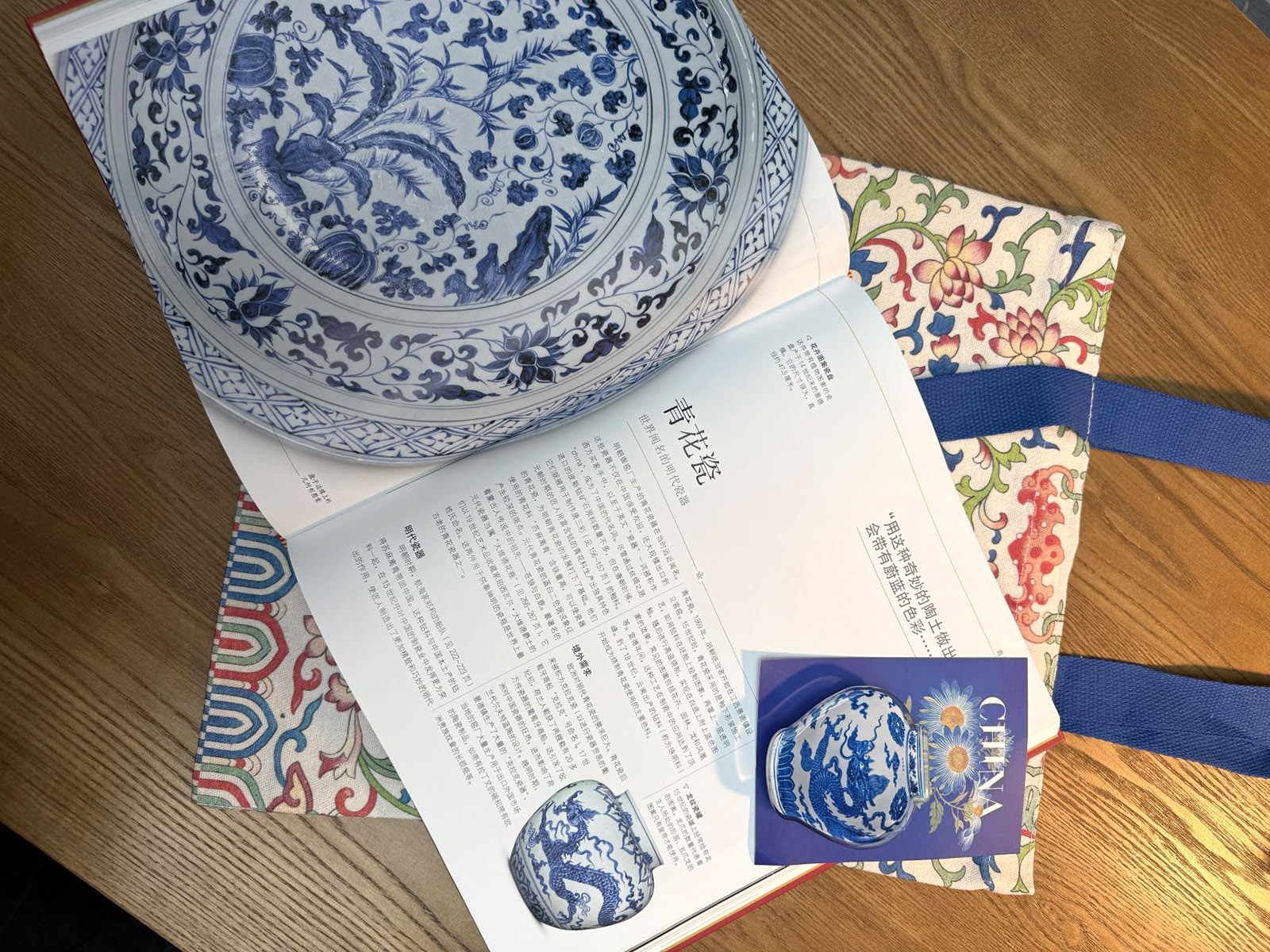

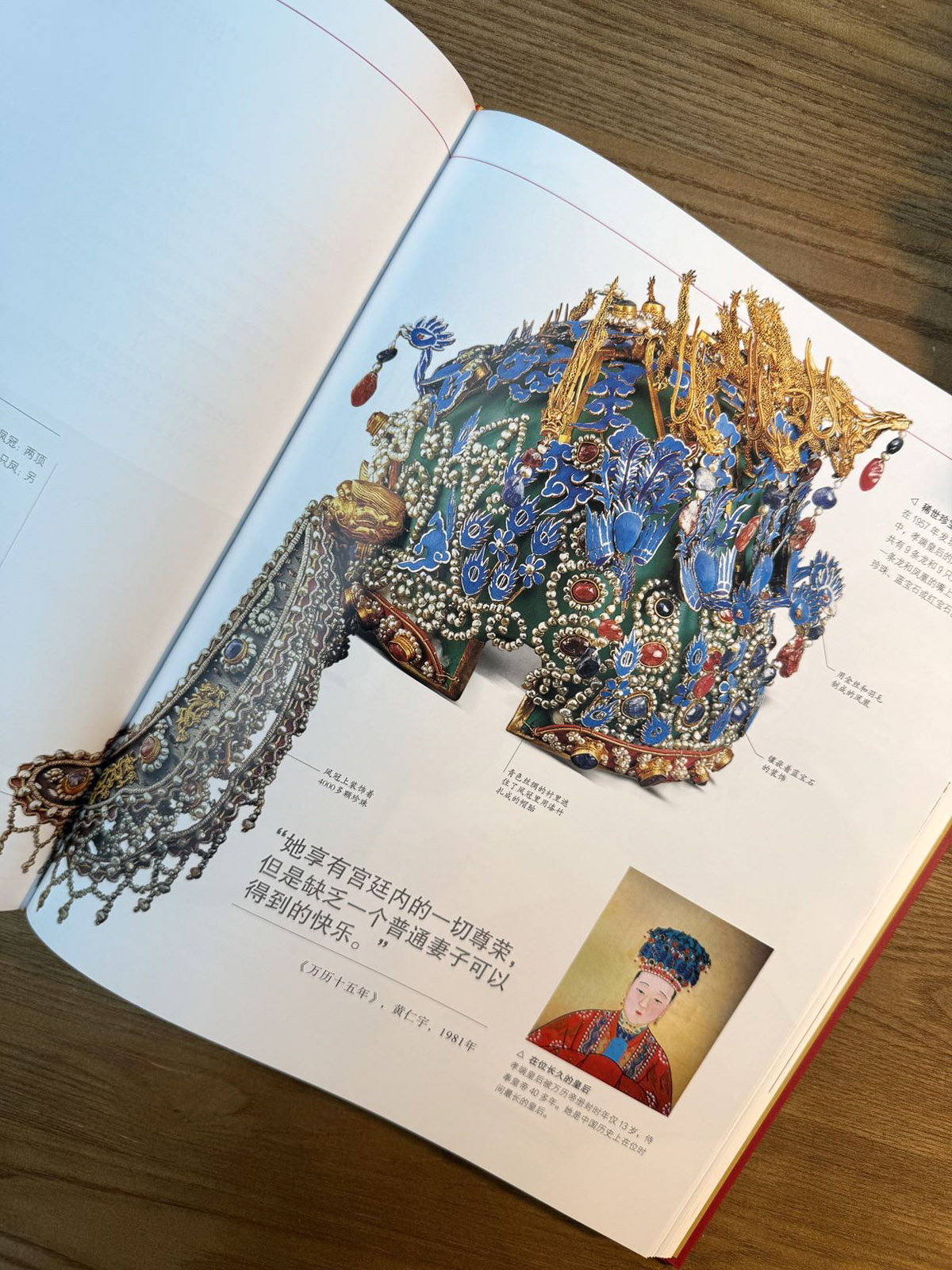

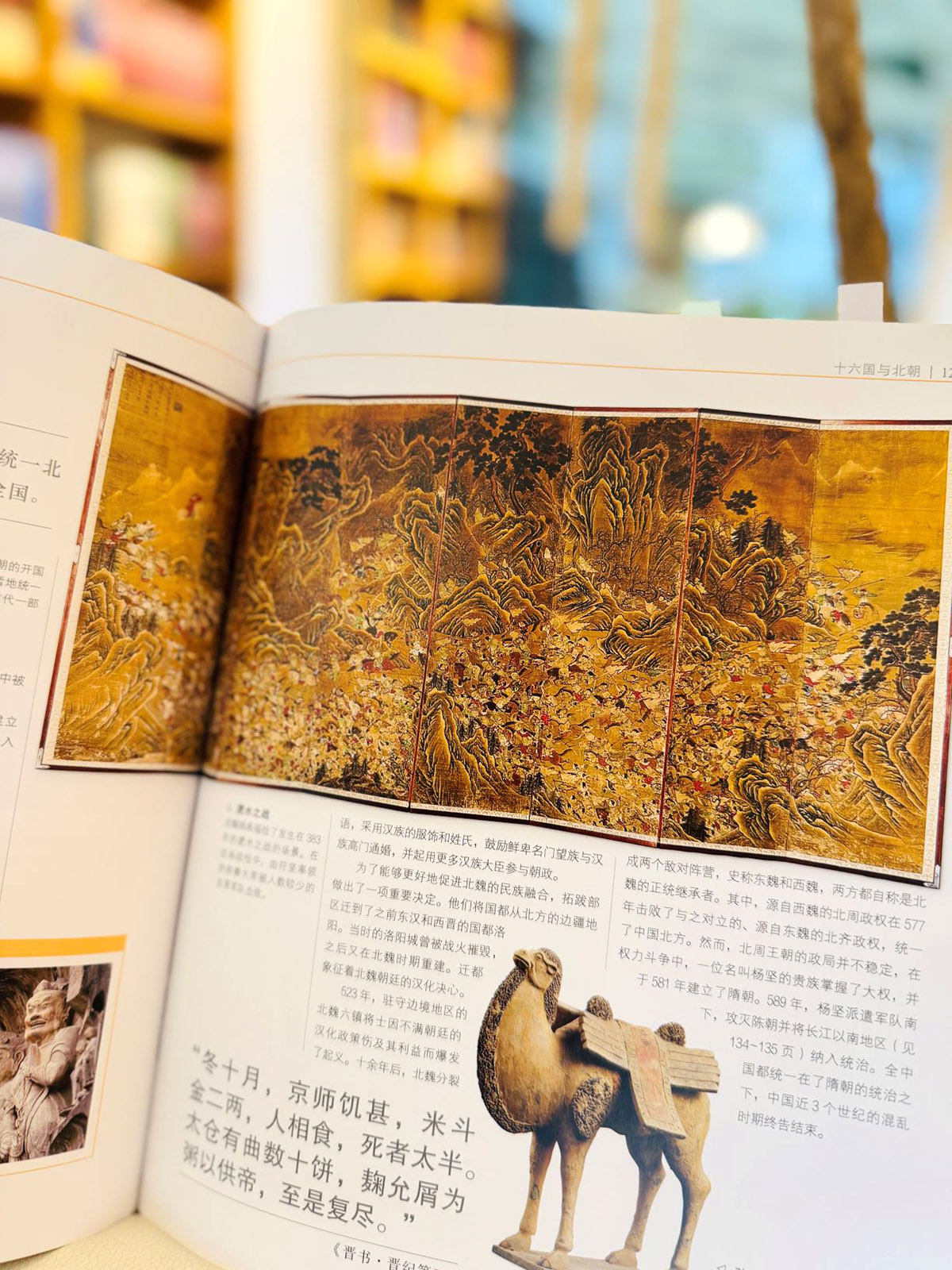

First published in English in 2020, the exquisitely printed chunky book does just that with aplomb and is a visual treasure featuring images of historical figures, cultural relics, art and artifacts — portraits, paintings or photographs. Some of them are not previously seen outside of China.

A collaboration between the Encyclopedia of China Publishing House and DK US, it covers more than 5,000 years of history in seven thematic chapters over 400 pages, presenting pivotal events that shaped Chinese history and laid the foundations of the modern nation.

Back in 2017, the two publishers reached an agreement to coproduce a book on ancient Chinese history for a global readership.

The collaboration aims to trace the evolution of Chinese civilization through a global perspective — examining political, economic, cultural, artistic, and technological developments — to showcase its enduring historical legacy, says Liu Guohui, former head of the ECPH, in the preface of the Chinese edition.

Written by six British historians and writers, the book has also been published in Italian, Japanese, Slovak, and Croatian besides English and Chinese.

Readers can appreciate the magnificent Terracotta Warriors from the Qin Dynasty (221-206 BC), splendid ancient architecture represented by the Forbidden City, and delicate porcelain, gold ornaments and silk while understanding the history-changing manufacturing technologies of compass and gunpowder and ancient craftspeople’s ingenuity in silk weaving, printing and iron smelting.

The Chinese version comes out with what Zhao Dongmei, professor of history from Peking University, calls “a good timing”. Zhao, alongside US Sinologist Edward L.Shaughnessy, is a consultant of the book.

By “a good timing”, she says she means it is a time when Chinese young people have a different vision of the past and present, and China’s development and international exchanges have reached a relatively high level.

It offers a perspective more international and modern into Chinese history, she says, paying much attention to culture, materials, and economy, including a great many photo archives about material civilization, she adds.

By “a more modern perspective”, she refers to a perspective especially compared with traditional Chinese history books, “which usually focus more on politics or political systems”.

In this book, instead, one can see more facets of ancient Chinese societies, such as science and technology, human life, economy, city, and also materials such as silk’s texture and patterns, which are always very important, Zhao says.

For example, there are specific pages dedicated to Su Shi, a great poet in the Song Dynasty, Italian adventurist Marco Polo, who spent 17 years in China in the 13th century and wrote a book introducing the mysterious Eastern country for the first time to the West, the making of silk, porcelain in the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), Chinese classic gardens, medical progress, oceanic exploration and “the Four Great Classic Novels”.

“History is such an entity: it slumbers in darkness until an observer’s perspective, like a beam of light, illuminates it. Without this light, it remains unseen. This ‘light’ is precisely the observer’s lens.

“Therefore, a book like this — take its treatment of the subjects I mentioned earlier — reflects how its creators focus intently. Indeed, when I say ‘they focus more’, it also mirrors how contemporary Chinese people show greater concern about those subjects than 20 years ago,” she says.

As time changes and the general living environment in China changes, people’s interest in the past also differs, she explains.

“I think the reason it resonates today — as I was saying earlier — is that now, Chinese people are developing a genuine, spontaneous interest in history. In the past, it was something you’re forced to study,” Zhao says.

She says she has seen a lot of examples online. One particular young woman that touched her is one who loves to make hanfu, a type of traditional Chinese garment.

The young woman is enthusiastic not only about costume, but also aircraft and auspicious cloud patterns. So, she designed a pattern that combines auspicious cloud pattern and the contour of a combat aircraft. Then she even had the fabric weaved.

“It feels strange to put the two patterns together, one being so traditional and the other so modern. But surprisingly, they appeared very harmonious,” Zhao says.

ALSO READ: Ancient books get a new chapter

“This young woman’s passion for history is entirely self-driven — a genuine love. Her devotion to history isn’t about rejecting the modern world or isolating herself from global perspectives. Rather, it’s about deeply understanding our past while skillfully integrating it with the present. Remarkably, she embodies this very spirit in today’s China,” she says.

“So the subjects in this book are more interesting for today’s Chinese people,” she says.

Contact the writer at yangyangs@chinadaily.com.cn