Ralph Vacchiano

NFL Reporter

The first half of the Super Bowl was uneventful, which is exactly what the people running it 12 years ago wanted. No controversies, no incidents, nothing to really worry about. Even Beyonce’s halftime show went off without a hitch.

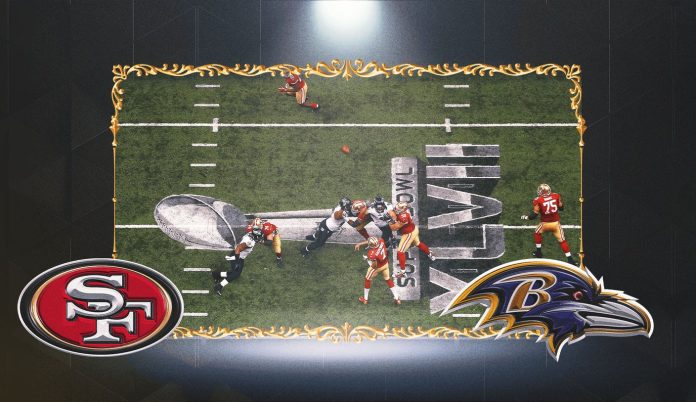

Truth be told, the game wasn’t all that exciting either. When Jacoby Jones returned the opening kickoff of the second half 108 yards for a touchdown, the “Harbaugh Bowl” — between John’s Baltimore Ravens and Jim’s San Francisco 49ers — was in danger of turning into a rout.

Meanwhile, high atop the massive Superdome in New Orleans, inside an electronic fortress they called “Control,” Frank Supovitz, the NFL’s senior VP of events, was finally able to relax for just a moment. The league had agreed to let CBS send a “60 Minutes” crew tail him for a behind-the-scenes story on Super Bowl operations. Now was a good time for him to do an interview and let down his guard.

So he stood there in Control, with his back to the field, as CBS reporter Armen Keteyian asked him a question. But before Supovitz could finish his answer, Keteyian cut him off.

“Uh oh,” Keteyian said. “That’s not good.”

Supovitz wheeled around and looked at the darkened arena below him and calmly said “All right. We lost lights.”

“I could see it in his eyes. It got very dark in NFL Control,” Supovitz recalled in an interview with FOX Sports. “Usually when you have 60 minutes standing next to you and something goes wrong, that’s a bad day.”

It wasn’t good, especially in those first few moments when half of the Superdome suddenly lost power a little more than half way through Super Bowl XLVII and nobody, anywhere had any immediate idea why. There was confusion on the field, uncertainty in the stands, and fear for some of the 75,000 or so fans, players, officials, workers and media packed into the dark arena.

And at that moment, it was clear that the legacy of that Super Bowl wouldn’t be the final game of Ray Lewis’ Hall of Fame career, Colin Kaepernick’s last moment on the NFL’s biggest stage, the “Harbaugh Bowl,” the 49ers’ wild but ultimately fruitless comeback, or the Ravens’ eventual 34-31 win.

That Super Bowl on Feb. 3, 2013 — the last one held in New Orleans before Super Bowl LIX kicks off on Sunday night — will forever be remembered for its 34 minutes in the dark.

‘We never simulated a power failure’

In the week before the Super Bowl, as fans began to fill Bourbon Street, there were some hints about what was about to occur. During a test run of Beyonce’s halftime show there were power fluctuations, according to people involved with the preparation, including the loss of a bank of lights.

The NFL was sure they had fixed that issue, though, and no one was worried that it might happen again. In fact, about a week before the game, at a Hyatt hotel near the dome, Supovitz oversaw what he called a “tabletop simulation” of the Super Bowl for several hours that included “everybody who would be in a decision-making role at NFL control.” They would imagine all sorts of disasters and emergency scenarios, and calmly game out how they’d handle them.

Or all but one.

“In all the years we did it,” Supovitz said, “we never simulated a power failure.”

“But that’s OK,” he added. “Because what it did was prepare us to just deal with whatever was presented to us.”

They were in the right spot for that on the night of the game. “Control” was a room filled with all sorts of cutting-edge technology and experts in a variety of fields. “We have eyes on everything,” said Brian McCarthy, the NFL’s VP of communications who was in that room that night. The room had “multiple screens (with) views of every possible angle inside the stadium and outside.”

Every piece of critical information ran through there. All the people in charge of every critical department were there.

“That,” McCarthy said, “is the nerve center of Super Bowl.”

And for the first few minutes of the blackout, that’s the only place where anyone was able to get information about what was going on.

‘Is this one of those 9/11 events?’

What was known at that point were only the basics. The Ravens controlled the first half of the game, taking a 21-6 lead on three Joe Flacco touchdown passes. Beyonce’s halftime show was spectacular, and the light show that went with it worked perfectly. The league and SMG, the managemen

t company that ran the Superdome, had decided during the week before the game to switch everything in Beyonce’s show to an outside power source, and it worked to perfection.

After it was over, the stadium lights powered back up and the game was back on.

Then Jones scored on the opening kickoff, and the 49ers ran three more plays — the last of which resulted in Kaepernick getting sacked. On the CBS broadcast, analyst Phil Simms was dissecting what went wrong on the sack when his voice disappeared mid-sentence. The broadcast continued with the now-silent replay for another 12 seconds before cutting to shot of players standing around on the field.

Only when they cut to a dimly lit Ravens coach John Harbaugh on the sidelines was it clear to the 164 million viewers around the world that, at 7:38 p.m. local time in New Orleans, the Superdome lights had gone out.

“I remember the first thing I thought was ‘Is this one of those 9/11 events?'” Solomon Wilcots, one of the CBS sideline reporters that day, told FOX Sports. “I thought ‘What’s going on here? Are we safe?’ So I started walking towards the tunnel because I saw some league people there gathering, and I started asking them ‘Hey, what’s going on?’

“But nobody could tell you.”

That’s because nobody knew. And it would be a while before anyone outside Control had any information at all. It wasn’t total darkness inside. Only the lights and power on the west side had gone out. But there was an eerie feeling looking over the shadowy field and stands from the press box up near the roof, and the information blackout made it seem worse.

Super Bowls are classified as Level 1 national security events by the Department of Homeland Security. There are always threats made towards big events like that. So inside the literal and figurative darkness, it was easy to fear the worst.

Down on the field, the players weren’t immune to that. At first, Wilcots said, they were all just milling about, looking around the stadium. Ravens quarterback Joe Flacco said later he even thought the field was still lit enough to continue the game. But at some point, Wilcots recalled players growing concerned about their family up in the dark parts of the stands and the lack of information they were getting.

The only thing information communicated to them was that, since the power was out in the 49ers locker room, both teams would have to stay on the field.

Meanwhile, John Harbaugh was livid. The Ravens coach was seen screaming at stadium officials and even at game officials. He was upset because the 49ers were apparently still able to communicate with coaches in their upstairs booths, while the blackout had cut the Ravens’ communications off completely.

“A total overreaction on my part,” he later admitted. “I didn’t have very much poise in that moment.”

Wilcots was stationed on the Ravens’ sideline and the power in his earpiece and microphone had gone out too, so he had no way of communicating with CBS’ producers. He figured that at some point, though, the power would be back up and they’d come to him, one of their reporters on the scene, looking for information.

“And when they do come to you, you better have something to report and you better have something credible,” he said. “But the league people weren’t telling me anything and the stadium ops people didn’t know anything.”

That’s when he went to John Harbaugh to “talk strategy.” But even that didn’t work out well.

“I said, ‘Hey coach, what are you telling your players?” Wilcots recalled. “He was like ‘I don’t know. What should I say?'”

‘You feel that feeling in the pit of your stomach’

When the lights went out, Supovitz admitted “We didn’t know” if it was terrorism, at first. All they knew was that the lights on the west side of the stadium were out, a sign that one of the two cables that brought power into the stadium had been “lost.” They’d quickly learn that everything was out on the west side — lights, escalators, the credit card machines at concessions stands. There were even elevators stuck with fans inside.

There was a remarkable lack of panic, though, as terrifying as it might have felt for some inside the dome. Supovitz, the man responsible for the event, said he snapped into “response mode” as did everyone around him in Control.

“It was almost like being in a boat in the middle of