In a small cavern south of Paris, scientists have uncovered what could be the oldest surviving three-dimensional map of a hunter-gatherer territory by reading between the lines on the floor.

Around 20,000 years ago, prehistoric people carved and smoothed the stone floors of this cave, creating what appears to be a miniature model of the surrounding valley, according to geoscientists Médard Thiry and Anthony Milnes.

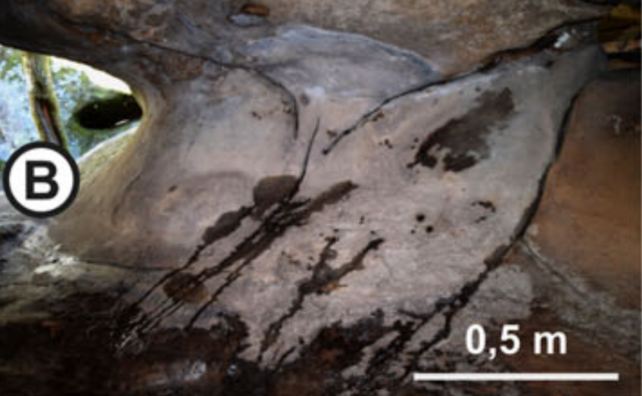

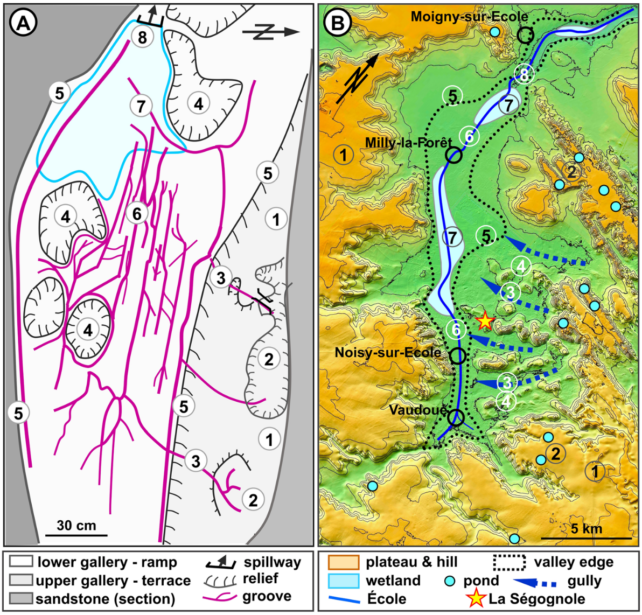

The surface of the cave, with carefully laid-out channels, basins, and depressions, would come alive with rivers, deltas, ponds, and hills as water from the outside world trickled through.

While not an exact geographical representation, the features on the cave floor seem to evoke a cartography, reflecting a functional river system that matches the valley where the cave is located.

Thiry and Milnes argue that the accuracy of the hydrographical network drawing suggests a remarkable capacity for abstract thinking among the ancient artists and their audience.

The cave, known as Ségognole 3, is part of a prominent complex of sandstone structures in France with over 2,000 Stone Age engravings.

Ségognole 3 stands out for dating back to the very end of the Stone Age, during the Upper Paleolithic era when early human settlements emerged.

While rock art from this period is scarce, archaeologists recently discovered two engraved horses on the walls of the cave, hinting at the symbolic significance of the site.

The grooves carved to resemble a female figure, including a pelvis and thighs, exhibit human manipulation that was previously overlooked.

Thiry and Milnes have traced the water flow patterns within the cave, uncovering how human actions altered the natural landscape to create a sophisticated water management system.

The authors describe how water seeped into the cavern through fractures and was directed across the floor into depressions, with the largest basin acting as a water tower feeding rainfall further into the cave.

These furrows, resembling rivers, converged downstream to create a network resembling river deltas and wetlands on the cave floor.

The absence of repeated shapes or patterns in the carvings suggests that this 3D picture map could have been used for various purposes like hunting, education, storytelling, or rituals related to water.

The terrace in the upper gallery of the cave may mirror the plateau of the surrounding valley, with the grooves representing rivers and various landscape features.

Thiry and Milnes caution that interpreting prehistoric carvings requires care, but the intricate details of this picture map suggest a deep understanding of the landscape’s spatial relationships.

This unique discovery challenges previous interpretations of prehistoric carvings, suggesting that ancient humans may have used such maps for a variety of practical and symbolic purposes.

The findings were published in the Oxford Journal of Archaeology.