Book Review

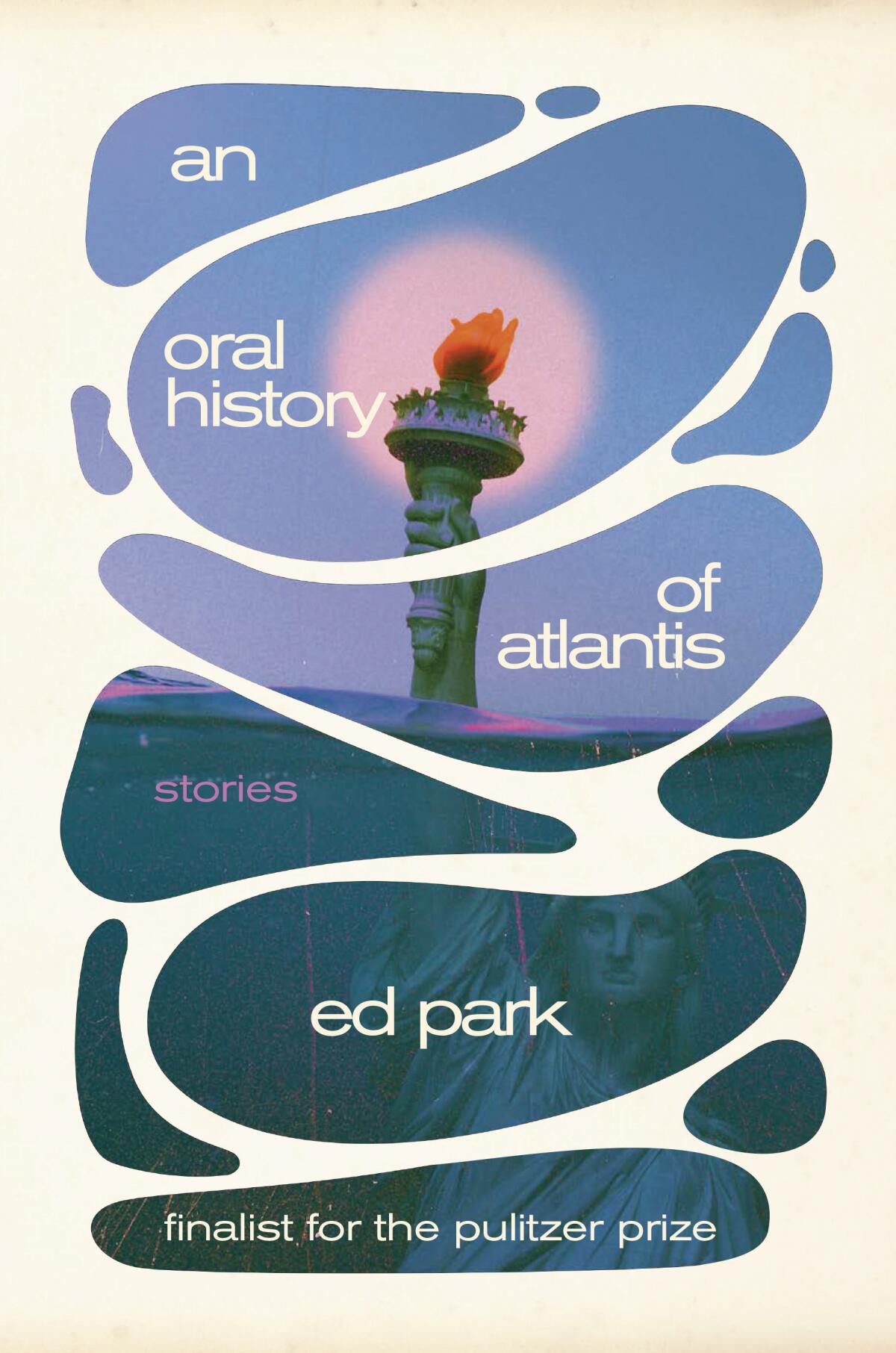

An Oral History of Atlantis: Stories

By Ed Park

Random House: 224 pages, $28

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Realism may still command the heights of American fiction, but insurgents are in it to win it. With titans such as Pynchon and DeLillo in their late 80s, now comes a generation captained by Ed Park, whose capacious, zany “Same Bed Different Dreams” won the Los Angeles Times fiction prize and was a Pulitzer finalist. Park samples many of that novel’s tricks in his new story collection, “An Oral History of Atlantis,” creating his own brand of Dada. Watch closely for patterns, though: films, ranging from pulp movies to Greta Gerwig’s “Barbie”; technology, from laptop passwords to algorithm fails; politics, from class warfare to the Korean conflict; sex, from hormone-crazed teenagers to a gaggle of lesbians; and metafiction, from Vonnegut to John Barth. If there’s a pea (or more) of genius hidden amid the walnut shells he’s shuffling across the book, it’s on us to find it.

“A Note to My Translator” serves as a preface: An acclaimed author, Hans de Krap, blasts E.’s egregious translation slip-ups. “Only 10 pages into my novel and already all seems lost,” he rants. “I no longer recognize characters, points of plot, dialogue. … Can you help me? Please?” De Krap isn’t just full of crap; this is Park’s appeal to his readers, drawing us into the collection’s linked pieces.

“Machine City” offers clues to his method — intersections between straightforward narrative and experimentation — as a middle-aged man remembers a role in a Yale student film. First published in the New Yorker, “The Wife on Ambien” is a fragmentary, oddly compelling riff on marriage. “An Accurate Account,” composed as a letter, urges us to question its accuracy. Park includes references to “Same Bed Different Dreams”: Penumbra College, for instance, appears in both books.

After the ornate sprawl of the novel, he revels in the shorter form, a palpable joy on the page. Irony has never had it so good.

He showcases figures with mysterious agendas, such as “Seven Women’s” Hannah Hahn, an enigmatic editor of a ‘90s East Village magazine. Midway through the story, the narrator reveals herself as the queer Miriam, who also recounts “Watch Your Step,” an edgy espionage tale set in Seoul and addressed to Chung — like Miriam, a spy, but a bumbling liability to their network. Both are Korean Americans who’d met in a theater-arts course in college, along with the sinister Johnny Oh, who is possibly a spy, too. This drama will not end well: “Watch Your Step” has a coiled energy, a cobra poised to strike.

Ditto for “Weird Menace”: Two Hollywood has-beens sip “itty-bitty drinklets” while screening a low-budget sci-fi DVD they’d shot in 1984. Neither have seen it in decades, yet they’ve reunited for an online viewing as fans of the cult classic follow at home. The story is pure dialogue between the star, Baby, and director, Toner: They’ve forgotten much of the plot and tipsily put it together. Park formats their banter in left and right margins with plenty of blank space, a visual back-and-forth that enhances spontaneity, a sense of unease. As Toner observes, “Meteors are metaphors, at some level.” Hannah makes a cameo, and a producer, Tina, shoves notes in Baby’s face, nudging the drunken actor toward a grim conclusion.

Park’s not indifferent to normie concerns, such as family tensions and floundering careers, communities and their discontents. His forays into realism pay off. In “The Air as Air,” Sidney, a vet maimed in Iraq, belongs to a recovery movement focused on breath. He agrees to meet his distant, macho father at a hotel near a California beach, a dash of beautiful prose: “The breeze freed fat drops from the trees as I walked from the parking lot to the turquoise hotel. Around a corner, a worker was standing by a ladder while another worker, unseen, narrated something in Spanish from the roof. Little green lizards and red crabs bright as poker chips scurried from my path,” the author writes. “I looked to the water. … No boats were out, and the ocean looked tight as cellophane.”

Mostly, Park challenges us to keep up: “The idea of unstable reality would be reflected in the form of the piece,” one character opines. The collection is like an elaborate crossword puzzle designed by Borges. “Slide to Unlock” employs second person as the protagonist sees his life flash before his eyes. Fritz, Hannah’s ex-husband, is literally losing his face, a conceit Park develops elsewhere in “An Oral History of Atlantis,” recalling Mariana Enriquez’s “Face of Disgrace.”

He invokes the mythological trope of the floating island (also an allusion to Atlantis) in “Well-Moistened With Cheap Wine, the Sailor and the Wayfarer Sing of Their Absent Sweethearts”: 18 women named Tina labor on an archaeological dig in the Pacific, funded by a shadowy foundation. There’s British Tina, Pageboy Tina, French Manicure Tina, Tina with the scorpion tattoo, even the Anti-Tina, a bit of fun tucked among Park’s coded riddles. The Tinas argue as they decipher an ancient script. A few want to escape the island. Is Gerwig available to direct the film version?

And is “An Oral History of Atlantis” a code-breaker or deal-breaker for readers? What are we to make of Park’s fusion of comedy and danger, his puns and wordplay and arcane theories? He’s testing our patience for excellent reasons: We’re complicit in his fiction, perpetrators at the scene of a crime, the act of reading a jumble of synapses in our brains, spinning in all directions like a spray of bullets.

“Everything could mean anything, as well as its opposite,” Park writes in his tale of the Tinas, a gesture to his craft. “You had to pick which side of the contradiction to embrace, or else record the whole unholy snarl itself.”

Cain is a book critic and the author of a memoir, “This Boy’s Faith: Notes from a Southern Baptist Upbringing.” He lives in Brooklyn, New York.