The Federal Reserve cut its benchmark interest rate by half a percentage point on Wednesday and signalled more reductions would follow, launching its first easing cycle since the onset of the pandemic.

The US central bank’s first cut in more than four years leaves the federal funds rate at a range of 4.75 per cent to 5 per cent. Michelle Bowman, a member of the Federal Open Market Committee, voted in favour of a quarter-point cut — the first Fed governor since 2005 to dissent from a rate decision.

The bumper half-point cut suggests the US central bank is seeking to pre-empt any weakening of the US economy and labour market after more than a year of holding rates at their highest level since 2001.

The last time the Fed cut rates by more than a quarter point was when Covid-19 tore across the global economy in 2020.

“The US economy is in a good place and our decision today is designed to keep it there,” Fed chair Jay Powell said at a news conference on Wednesday. “This recalibration of our policy stance will help maintain the strength of the economy and the labour market and will continue to enable further progress on inflation as we begin the process of moving towards a more neutral stance.”

Powell said rates were not on a “preset” path, noting that if inflation proved sticky the Fed could “dial back policy restraint more slowly”. Equally, the central bank was “prepared to respond” if the labour market weakened unexpectedly, he added.

“We do not think we are behind [in cutting rates],” Powell said. “But you can take this as a sign of our commitment to not get behind.”

In a statement on Wednesday, the FOMC said it had gained “greater confidence” about inflation, even though it remained “somewhat elevated”.

US stocks rallied immediately after the announcement and peaked shortly after Powell began his press conference. The S&P 500, which was steady earlier in the day, jumped as much as 1.1 per cent, briefly surpassing its intraday record high but eased to close slightly down on the day.

The Treasury yield curve steepened, with the spread between 10-year and two-year bonds, an indicator of future growth expectations, reaching levels last seen in June 2022.

The yield on the policy-sensitive two-year note slipped 0.06 percentage points to 3.59 per cent following the Fed’s announcement but later climbed back to 3.63 per cent. Bond yields move inversely to prices.

Asian markets rallied on Thursday morning. Mainland China’s CSI 300 stock index rose 0.8 per cent, Hong Kong’s Hang Seng index advanced 1.8 per cent and Japan’s Topix was up 2.4 per cent.

The yen weakened to ¥143.2 against the dollar after strengthening past ¥140 earlier in the week, as traders anticipated the Bank of Japan would not raise rates at a policy meeting concluding on Friday.

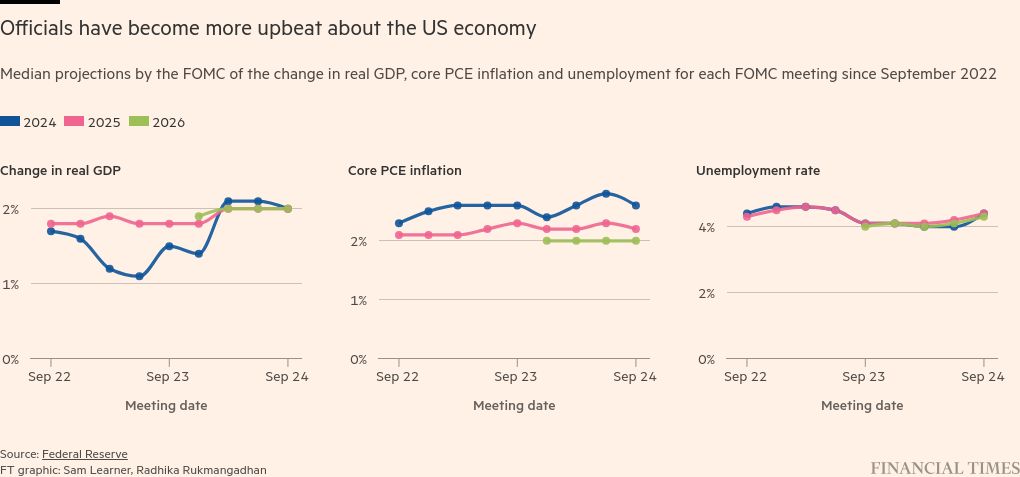

In the latest “dot plot” of officials’ forecasts, most expected the policy rate would fall to 4.25 per cent to 4.5 per cent by the end of 2024, suggesting another large half-point reduction at either of the two remaining meetings this year or two quarter-point reductions. Overall, that is a significantly larger reduction than the quarter-point cut projected by most officials in June, when the dot plot was last updated.

Two of the 19 officials who pencilled in estimates thought the Fed should hold off after Wednesday’s reduction, while another seven forecast only one more quarter-point cut this year.

Policymakers also expected the funds rate to fall another percentage point in 2025, ending the year between 3.25 per cent and 3.5 per cent. By the end of 2026, it was estimated to fall just below 3 per cent.

Some analysts said the Fed’s decision pointed to underlying concerns about the economy.

“It’s a very muddy picture out there,” said Jack Manley, global market strategist at JPMorgan Asset Management. “The macro data are not nearly as clear-cut as we’d have liked. The Fed is looking at this economy and saying: ‘We’re making more progress on inflation than we thought, but we think the labour market is starting to slip and it could get worse.’ That to me is not a good sign.”

Wednesday’s decision is a milestone for the central bank after more than two years battling inflation — and a significant moment in this year’s presidential election.

Falling borrowing costs will be a boon for Democratic candidate Kamala Harris, whose campaign has been dogged by voter disquiet over high living costs even as the US economy has boomed.

President Joe Biden welcomed the Fed’s move, saying in a post on X: “We just reached an important moment: Inflation and interest rates are falling while the economy remains strong. The critics said it couldn’t happen — but our policies are lowering costs and creating jobs.”

The cut comes as Fed officials grow more confident that inflation is under control and turn their focus to the health of the labour market.

After peaking in 2022 at about 7 per cent, the personal consumption expenditures price index was just 2.5 per cent in July, closer to the Fed’s 2 per cent target.

But jobs growth has cooled in recent months and other measures of demand, such as vacancies, have also slowed, even though the number of Americans filing for unemployment benefits remains historically low.

The Fed has made clear it does not want to see further labour market weakening amid concerns it has waited too long to loosen its grip on the economy by lowering borrowing costs.

In projections released on Wednesday, most officials forecast the unemployment rate to peak at 4.4 per cent over the next two years, up from its current level of 4.2 per cent and higher than June’s estimates, while economic growth stabilises at a 2 per cent rate over the next several years.

Officials also forecast a more benign inflation backdrop, with PCE falling back to target in 2026. The median estimate for “core” inflation, which strips out volatile food and energy prices, was revised lower to 2.6 per cent for this year, before falling to 2.2 per cent and 2 per cent over the next two years.