Joshua Clover lived for moments like these, days or nights “when the partisans of riot exceed the police capacity for management, when the cops make their first retreat…when the riot becomes fully itself, slides loose from the grim continuity of daily life.” Published nine years before his death this April, and inscribed “for Oakland, for the comrades,” his singular Riot. Strike. Riot is as much written about such moments as it is written from and to them. Like many of his friends, I couldn’t help but hear Joshua this past week, his commentary, his theories, his hilarious quips and stupid puns, as brave, ingenious partisans in greater Los Angeles and across the country ran ICE agents out of neighborhoods, blockaded ICE offices, and fought through the alphabet soup of federal sent as reinforcements.

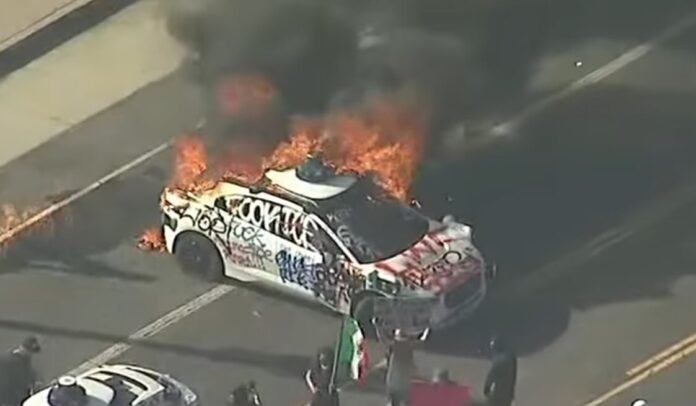

We would no doubt be comparing notes, or writing something together, as we did on many like occasions. A line of Waymos lured into the fray and lit on fire, a ten-ton blob of lime scooters zip-tied together, blockading the ICE loading docks. Is this the first app riot in the US? What do you think about tenant organizations gathering to evict ICE from local hotels with noise demos? Joshua and I shared a horizon, a vocabulary, a history, and a world. Theory was immanent to practice, we agreed. The task for communists in the face of such moments of possibility was not to give marching orders, to lead or educate, but to amplify what struggle has to say, to clarify and synthesize what practice had already made clear. “The subjunctive is a lovely mood, but it is not the mood of historical materialism,” he writes.

What is clear now? So far, not much. This is a riot unlike the Los Angeles riots of 1992—for Joshua the paradigm of the riot in our era—or the riots spreading from Minneapolis across the country in the summer of 2020. Each of these was reaction to a specific act of antiblack police violence—the beating of Rodney King, the murder of George Floyd. In 2025, the riots we see are preventative, defensive, and yet paradoxically aggressive; they aim to interrupt specific instances of police violence, to thwart, harry, and besiege Trump’s disappearance squads. Whereas the riots of the 2010s tended to absolutize themselves, as Joshua notes, offering no demand beyond maximal negation of the repressive state, here there is an implicit and achievable demand—stop the deportations and detentions. Trump could lose. As such, it has been the state which escalates, absolutizes, and which stands to radicalize the anti-ICE movement into something with broader, deeper and perhaps even revolution aims. In 2020 it took nearly a week for the National Guard to be sent in. In 2025 it took two days.

One reason for this escalation is the front-footed nature of the riots, their focus on impeding ICE. But more important is the ambitious, contradictory, and destructive agenda which Trump and his administration has set for itself—unsurprisingly, Trump has fallen far short of the millions of detentions and deportations his depraved loyalists were promised. The methods available, however, are grotesque and deeply unpopular, even with some of his supporters. Is escalation here an earnest attempt to do what would be needed, effectively placing so-called “sanctuary cities” under military occupation, and beginning to construct the massive deportation machine necessary? Or is this theater designed to mollify his base and allow him to blame the obstruction of liberal mayors and governors? Insofar as the resistance shows no signs of stopping, we are primed to find out.

Key to Joshua’s theory of the riot, past and present, is that riots occur definitionally in the space of circulation rather than production. In the period before the emergence of industrial capitalism, the golden age of riot, when hunger became unbearable, rioters intervened in the market directly, seizing grain and setting its price. Displaced for a couple hundred years by the consolidation of the workers’ movement and with it the central tactic of the strike, centered on production and labor, the riot returns in the late twentieth century to haunt a space of commodity circulation occupied by the police, whose rule over the market is now absolute. What is interesting about the burgeoning movement against ICE is that while it does not concern production directly, it is nonetheless about labor, inasmuch as legal status is a product of state regulation of labor-markets and the division of labor, “the bloody legislation against the exploited” that has attended capitalism since its birth. These are therefore circulation struggles insofar as they are “forms of collective action” comprising “participants with no necessary kinship beyond their dispossession.” They intervene, however, within the circulation of labor-power and its legal regulation by the state, confirming Joshua’s assertion that today’s struggles are often surplus rebellions—rebellions of the dispossessed rather than the exploited—with their basis in “a global division of nonlabor.”

Concentrated and focused as they are, the geography of these confrontations in some way resembles the eighteenth-century export riots Joshua describes in his first chapter, which would focus rioters upon the ports, depots, and granaries. A riot, but also an occupation or blockade. This gives the pattern of action a high degree of consistency, militancy, and discipline. Close quarters allow for ad hoc coordination, multiplying tactical ingenuity. Such powers of concentration are explosive—think for example of the crowd which converged upon and the Minneapolis PD’s third precinct after the murder of George Floyd and set it aflame. But they can also lead to ritualistic, enervating confrontation for the sake of confrontation that does little to unsettle the party of order. This is perhaps the danger for the movement. As state power hardens against this first assault, the movement may need to become more dispersive, distributed, and adroit, simply as a matter of survival. Because ICE can strike anywhere, the movement will need to find a way to be everywhere.

As riot spreads, Joshua reminds us, it also splits. It opens rifts in class society which only the passage to revolution can overcome. The first of these rifts is the “nearly universal convention of riot prime…that shortly after it burst forth and experiences a victory either substantial or apparent, it divides into two impulses,” one of which is “an attempt to swell the ranks by mobilizing public sympathies, using to its advantage media coverage and other discursive apparatuses…drawn ineluctably toward some version of respectability politics and generally toward the moral suasion of passive civil disobedience and nonviolence in general.” Here we see this first rift emerge with the anachronistic No Kings protests, bedecked in American flags and funded by Walmart, aiming to delimit the confrontation with the state and transform it into a conflict for rather than against the rule of law, against ICE but for the police as such. The emphasis on civility, non-violence, and de-escalation presupposes and in fact requires another movement that is savage, violent, and escalatory. A second rift emerges through the pattern of the “the double riot” observed in Oakland and London, Greece and Spain, epitomized by the twinned banlieue riots of 2005 in France and the pursuant but disconnected anti-CPE student riots. The double riot emerges as and from a rift within the proletariat, corresponding to different class fractions. “One riot arises from youth discovering that the routes that once promised a minimally secure formal integration into the economy are now foreclosed. The other arises from racialized surplus populations and the violent state management thereof.” Are today’s events the reflection of the Gaza solidarity encampments of 2024? If so, we see a rift traversed by new diagonals, as kids in keffiyehs throw barricades in the path of ICE. To the rift corresponds also the swerve cutting across these divisions. Here, in the limits of the riot, we see its overcoming and its passage to revolution.

Joshua’s book was often read—or more likely, not read—as programmatic endorsement of riot, rather than a theory of its passage to the limit. “Once fire is the form of spectacle the problem / becomes how to set fire to fire,” he writes in Red Epic, his poetic companion to Riot. Strike. Riot. Organization adds. Self-organization multiplies. The organization of self-organization sets to fire to fire, adds multipliers, exponentiates. The name that Joshua and I give to this organization self-organization, following on Kristin Ross’s revelatory scholarship and our own experiences, is the commune, “beyond strike and riot both.” The commune is a tactic of social reproduction, overcoming the division between production and consumption that the opposition of circulation struggle to production struggle assumes. Here, however, means becomes end—tactic becomes “form of life.” The commune is process, activity, event; it will “develop where both production struggles and circulation struggles have exhausted themselves.” We can see glimpses of this commune in the streets of Los Angeles, anticipations of spaces of real sanctuary, community, and freedom that could render legal status meaningless. The key presupposition of such overcoming, Joshua writes, is “the breaking of the index between one’s labor input and one’s access to necessities.” In The Future of Revolution, I begin where Joshua’s book ends, with the commune-form and the Paris Commune, developing from there an understanding of how, in positive terms, the opposition between production and consumption can be overcome by breaking the index between them—which is to say, the wage and, with it, money. In the book he was working on when he died, Joshua sought likewise to develop his notion of the commune against the value-form through a study of infrastructural blockades and protest camps that required alternative structures of free social reproduction. From the blockade and communal kitchen derive the fundamentals of communal reproduction.

From circulation struggles to the commune, then. Joshua loved to circulate but he also loved to commune. He had longs legs, big lungs, a big heart. He was a circulation athlete: marathon runner, road biker, kayaker. He loved to wander the world’s cities, labyrinths of the commodity-form, drifting against the grain of capital. He got around, got out there, got after it. He had an incredible ability to set words in motion—a font voluminous of razor-sharp sentences and shapely lines, always writing, messaging, collaborating. He never gave up the habit of working under deadline learned from his time as a professional journalist but his assigning editor was history itself. To collaborate with him was to feel the pressure of time historical—he caught you up. At the same time, Joshua also liked to hang out, he liked to gather everyone he loved in one place. He was busy, but he showed up for people. If you were his friend, he had your back, and he each day held up dozens of his friends, comrades, students, strangers. He made things possible for others, provided the infrastructure for the circulation of practices, ideas, people. He was always ready to wash pepper spray from your eyes, to pull you away from the snatch squad. He had my back, for nearly twenty years, in every way possible. It is no surprise then that his thought had moved from circulation, from the white-hot intensities of the riot to the quieter camaraderie of the communal kitchen. One book whose protagonists throw rocks at cops and another where they just do the dishes.

Joshua loved his friends, his comrades, he loved cats and really all animals. He liked kids more than he would admit. In the last months of his life, bedridden and barely able to read or write, he spent most of his time exchanging long voice messages with his vast network of friends and comrades all over the world; he kept up with comrades in prison and managed to comment on his students’ final dissertation chapters. The infrastructure of comradeship, of friendship—that was Joshua. In capitalism, the exploited generations of the dead weigh heavy upon us as inert fixed capital, chaining us to the law of value. But infrastructure can also be a gift from the past to present, as it would be in communism, a materialized ancestry. He is still present, then, as long as he is remembered and read. The theses of Riot. Strike. Strike are at this point largely accepted, incontrovertible, a part of a new communist common sense. In the novels of Joshua’s friend, Kim Stanley Robinson, Riot. Strike. Riot has imaginary readers across the twenty-first century. His readers—real and imaginary—are probably out there doing the thing right now.

[book-strip index=”1″]