Catherine Michaux and her husband Jean Yves seem to fit squarely into the target consumer group for electric vehicles.

A retired lawyer, she no longer needs to commute. The couple own a home where they could charge an electric vehicle on their own time, at lower cost. They have tried out electric car rentals in their small French village near Nice last year and enjoyed the experience.

Even so, the couple says they are put off by the cost of buying an EV. “People will never be able to afford electric cars. It’s impossible,” Michaux says.

The challenge is to kick off old habits, her husband adds. “We’ve always lived with engine cars. Those are the reflexes we have. We know there are gas stations all along the highway. Here, you have to think about your journey and plan it out a bit, and download a mobile app.”

Fifteen years after Nissan released the world’s first mass-produced electric vehicle in 2010, consumers in much of the world are still stubbornly reluctant to switch away from combustion-engine vehicles to fully electric.

What carmakers initially embraced as a necessary evolution has increasingly become an existential crisis for an industry that has spent tens of billions of dollars to develop electric vehicles and the batteries that power them with the hope that consumers will buy into the technology.

Last week, Northvolt, Europe’s leading battery champion, filed for bankruptcy, throwing the continent’s entire industrial strategy under question. Vauxhall owner Stellantis on Tuesday announced plans to shut its van factory in Luton, putting about 1,100 jobs in the UK at risk, only weeks after Volkswagen warned of unprecedented plant closures. Ford also recently unveiled plans to cut about 4,000 jobs in Europe to address slower than expected demand for EVs.

© Matthieu Audiffret/FT

Mathias Miedreich, former chief executive of battery materials maker Umicore which will join German automotive supplier ZF Friedrichshafen in January, says European carmakers and suppliers are likely to continue focusing on getting leaner next year instead of building capacity to expand EV sales. “The year of the rebirth of the electric vehicle is probably 2026, and not 2025,” Miedreich says.

America is also likely to fall further behind in its green transition, given president-elect Donald Trump’s promises to kill the generous subsidies for electric vehicles. Despite President Joe Biden’s ambitious target of having EVs make up half of all new cars sold in the US by 2030, they were only 10 per cent of the market last year.

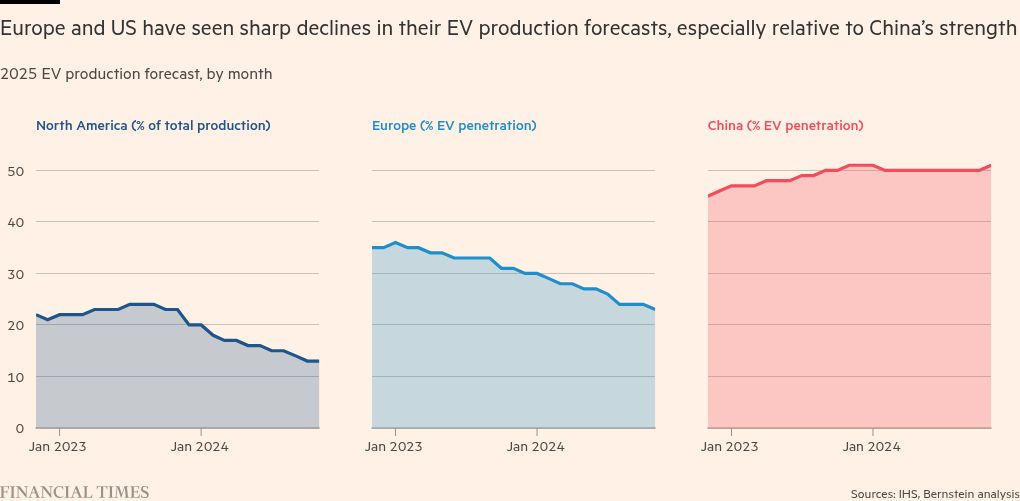

The industry’s capacity to build EVs is expected to fall further next year with carmakers having revised their EV production plans by 50 per cent in the US and 29 per cent in Europe, according to Bernstein estimates. The penetration of EVs is expected to reach 23 per cent in Europe, 13 per cent in the US in 2025.

“The EV production forecast for 2025 has seemingly only gone one way — down,” Bernstein analyst Daniel Roeska wrote in a report.

The reasons for the slowing growth in EV sales range from the high upfront costs combined with concerns over driving range and charging infrastructure. The promise of lower energy prices faded with the war in Ukraine while high interest rates globally have pushed up monthly lease payments.

According to analysis by NGO group Transport and Environment, the average price of an EV in Europe was around €40,000 before taxes in 2020. Today, the price is around €45,000.

A separate study by the European Commission suggests that the median price European consumers are prepared to pay for an EV is €20,000, including new and secondhand sales.

…