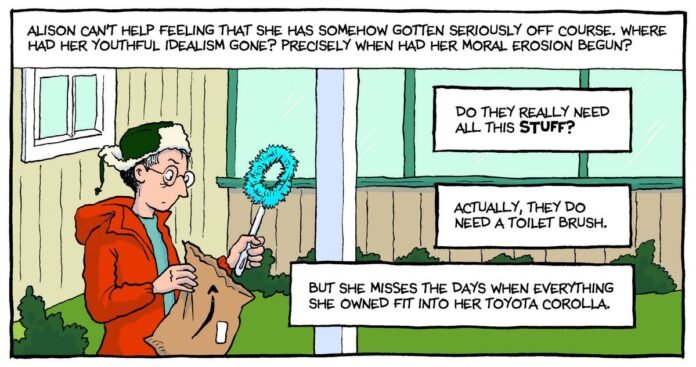

A panel from Alison Bechdel’s new book, Spent.

Art: © 2025 Alison Bechdel, Courtesy of Mariner Books and HarperCollins Publishers

Alison Bechdel first realized she was a lesbian in college, after reading a suspicious number of books on the subject. For the burgeoning cartoonist, sex was as much a mental pursuit as a physical one, “a field of study that engaged both intellect and instinct in a fusion so heady, so visceral, indeed, so all-consuming” that she neglected her actual schoolwork. The introduction to the omnibus edition of Bechdel’s comic strip Dykes to Watch Out For shows the young author sixty-nining with her college girlfriend next to a spread-eagle collection of Adrienne Rich essays. Soon enough, Bechdel would discover that sex with other women was “merely the tip of the lesbian iceberg.” “What lurked beneath was a worldview, an entire logical system in which homophobia was inextricably linked to sexism and racism and militarism and classism and imperialism,” she has written. “It was a compelling schema, and if in my excitement I confused the personal with the political, well, that was part of the idea.” This confusion was on full display in Dykes to Watch Out For, which ended its 25-year run in 2008. DTWOF, as it became known to fans, was a pulpy melodrama about a group of midwestern lesbians who discuss the Gulf War in bed and cruise for babes at protests. Says one dyke, “If I can’t ogle, I don’t want to be a part of your revolution.”

This thrilling collapse of registers was a source of tremendous anxiety for Bechdel. “It’s all a sham! I’m a fraud, a fake, a phony!! A closet closet case!!” Bechdel writes in an early autobiographical comic. “While my cartoon characters are very politically active, in my personal life, I shirk responsibility.” A few years later, she would note that cartoonists, in particular, tend to “get away with being obsessively self-absorbed in a way even memoir writers don’t.” Twice beware the graphic memoirist! The breakout success of Bechdel’s 2008 memoir, Fun Home, about her closeted father’s suicide, seems only to have buttressed her sense of herself as a navel-gazer. “You smarmy, self-indulgent, solipsistic piece of shit,” she mutters in her second memoir, Are You My Mother?, as she prepares to tell her mother that she is writing about their family. When her mother tells her that the self has “no place in good writing,” Bechdel puts up a half-hearted defense: “Yeah, but don’t you think that if you write minutely and rigorously enough about your own life, you can, you know, transcend your particular self?”

Perhaps it was inevitable then that Bechdel would arrive at autofiction. Her new novel, Spent, tells the story of one Alison Bechdel, a tetchy lesbian cartoonist running a pygmy-goat sanctuary in Vermont who is trying to write a memoir about the corrupting influence of money. Meanwhile, down the road, Alison’s friends Sparrow and Stuart embark on a surprisingly sweet experiment in ethical nonmonogamy, supported by a familiar group of aging dykes whom Bechdel has grandfathered in from DTWOF. (The effect is of an author hanging with her own creations.) Once more Bechdel gives us people grappling with their own political complicity, people whose lofty ideas about society far exceed their ability, or indeed willingness, to change it. That most of them are dykes is not an accident, and not just because Bechdel has spent her life watching out for them. In the ’60s, they used to say that feminism was the theory and lesbianism was the practice; a better way to put this is that lesbianism tends to make theorists of its practitioners. “It was only my lesbianism, and my determination not to hide it, that saved me from being compliant to the core,” Bechdel writes. The intriguing idea here is that the practice of lesbianism, thanks to its marginal status within society, implies certain political ideals — smashing patriarchy, protesting war, resisting capitalism — that the lesbian nevertheless cannot satisfy. Reading Spent, we might conclude that Bechdel’s lesbian is doomed to hypocrisy. Or we might say, more interestingly, that lesbianism is a case study in the paradox of political commitment.

Spent is not Bechdel’s best work, but it is an improvement over her more recent books. The memoirs that followed Fun Home suffer increasingly from a monologism that is curiously amplified by the graphic medium; reading them can feel a little like watching a movie dominated by voice-over. Spent is a welcome return to the bickering polyphony of Dykes to Watch Out For, with each member of the ensemble acting as a zany spokeswoman for one of Bechdel’s many conflicting views. It is a pleasure to see Bechdel take up the satirist’s pen once more, even if the gags can be too broad. Having some queer zoomers start a podcast called Polycrisis that looks at climate change “through a poly, anticapitalist, vegan lens” is a bit too much; having Bill McKibben wander on as a guest is just right. Other elements try the reader’s patience: A subplot about Alison’s Trump-supporting sister, Sheila, with whom she reluctantly tries to find common ground, is an inorganic morality tale. Similarly, Alison’s half-baked idea for a Queer Eye–like reality show about ethical living under capitalism is clearly an excuse to procrastinate; one also wonders if Bechdel, like Alison, is occasionally trying to pass off her writer’s block as writing. (What would have been so bad about a straightforward, novel-length sequel to DTWOF, whose abrupt hiatus in 2008 left readers with a cliffhanger?)

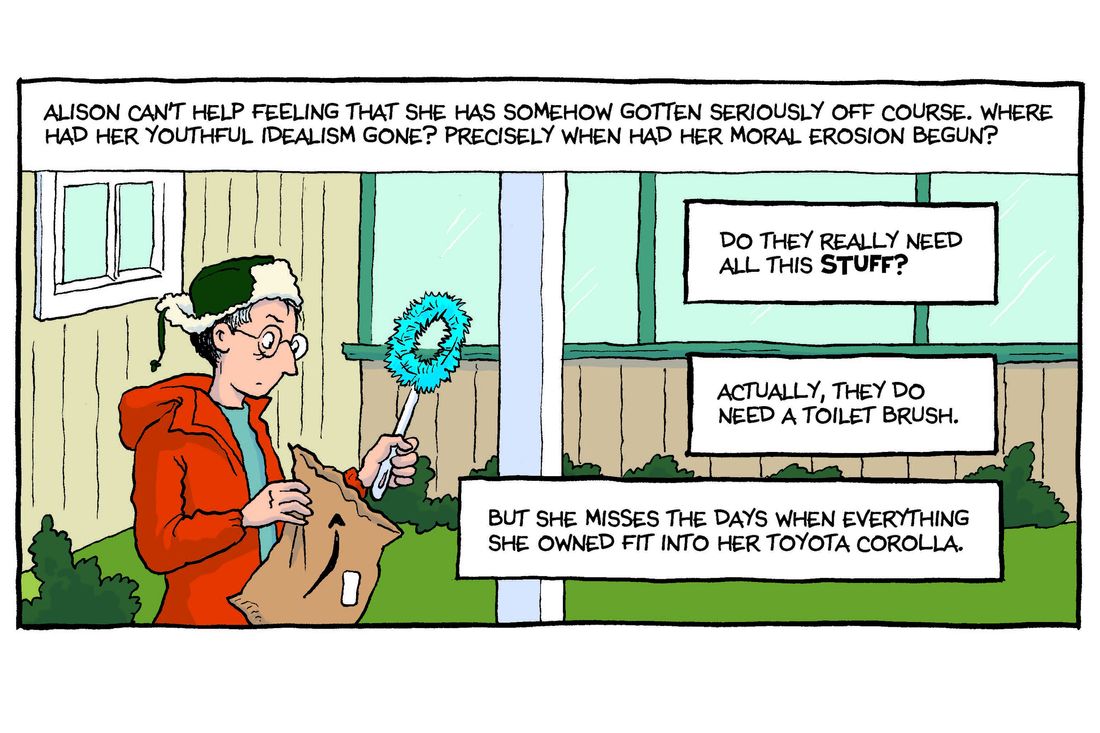

Spent is Bechdel’s first book since her longtime publisher was acquired by the Murdoch-controlled HarperCollins. “Aren’t they owned by the conservative billionaire family that hit TV show is based on?” asks Alison’s wife skeptically. After some obligatory agonizing, Alison takes the money. She hopes to make up for this by writing a new book that will “put the final nail in the coffin of late-stage capitalism.” But she gets 60 pages into Marx’s Capital before getting distracted. “How Alison had inveighed in her comic strip against Amazon.com back in the 1990s!” Bechdel’s narrator sighs, noting that today Alison’s online-shopping habit has “probably singlehandedly funded that lunatic Bezos’s rocket ship.” Alison wishes she could pinpoint the moment when she lost her “youthful idealism,” but this wish only feeds into the patently self-defeating belief that an ever more rigorous examination of her “privilege and complicity” will somehow release her from intellectual paralysis. The fact is that Alison spends most of Spent trapped inside her own head, even when she tries to step outside of it. (In a gag dating back to Bechdel’s earliest comics, the names of Alison’s literary agent, talent agent, and book editor are all anagrams for “Alison Bechdel.”)

Art: © 2025 Alison Bechdel, Courtesy of Mariner Books and HarperCollins Publishers

The reader of Dykes to Watch Out For will recognize Alison as a new, unimproved version of Bechdel’s comic-strip alter ego, Mo: a total drag who rails against the capitalist war machine but is too self-absorbed to picket a homophobic business. Bechdel describes Mo as “motivated by free-floating guilt in combination with hypersensitive moral fiber”; her girlfriend lovingly calls her a “weak-willed wretch.” She also looks very much like Alison Bechdel, clad in a Where’s Waldo–style turtleneck that suggests someone who loves being looked for and hates being found. (Bechdel is aware of the similarity: The “real” Mo can be spotted in Spent at a crowded farmers’ market, where she is perusing a stack of matching Waldovian beanies.) Even when Mo attacks others, her sadism is ultimately directly at herself, whom she seems to blame for every injustice. “I don’t understand how people can lie around making love when there’s so much misery and desolation in the world!” Mo laments in her first appearance, desperate to get laid. Indeed, Bechdel often suggests that what stands between Mo and her principles is, in fact, her commitment to them. “Please, Sydney” she tells her girlfriend after wishing that lesbians would get back to dismantling the monogamous family. “I’m expressing an ideological conviction, I’m not talking about real people.”

Real people, it turns out, are more complicated. While Alison rage-reads the news and helps her wife shoot Instagram videos, her old friends Lois, Ginger, Sparrow, and Stuart are still living together in mild communal chaos. Veering into a midlife crisis, the bisexual Sparrow and her partner, Stuart, agree to pursue a polyamorous entanglement with Sparrow’s old crush, Naomi. Alison’s wife cynically glosses them as a “bored straight couple looking for a bi woman to spice things up,” but things go remarkably smoothly for the inchoate throuple, which by the novel’s end appears happy and durable. The principal drama within this new arrangement concerns how Sparrow and Stuart should tell their nonbinary kid, J.R., a spoiled student activist who is threatening to drop out of college. It is interesting that the most emotional arc of Spent should be a conventional coming-out story, albeit generationally flipped: Here it is a mother and father who must sheepishly come out to their much woker child. J.R., who is poly themselves, joyfully takes the news as a sign that middle age hasn’t totally sapped their parents of radicalism.

If polyamory feels like a fashionable subplot for Bechdel to tackle, this is only because heterosexuals have recently discovered in it a promising balm for yuppie malaise. For the lesbian, it is a locus classicus. “You don’t understand, Rita!” one dyke reassures her jealous lover in a 1986 strip. “I’m not simply non-monogamous, I’m anti-monogamy!” Indeed, commitment is probably the central theme of Dykes to Watch Out For. “How thrilling to be free of the suffocating constraints, the shackles and trammels of thousands of years of heterosexual dogma and convention!” Bechdel writes in a 1992 comic, before adding: “Still, the picket fence would be awful nice …” The lesbian feminist finds herself caught in an unhappy ménage à trois: Either her commitment to her political ideals prevents her from committing to a single partner, or her desire for monogamy makes her unfaithful to her own professed values. Mo constantly bashes monogamy as an institution but lives in fear that her girlfriends are cheating on her, which sometimes they are. Longtime couple Toni and Clarice struggle for years with thoughts of infidelity, even as they rack up a mortgage, a son, and a civil union. They consider polyamory, though its relative lawlessness frightens them. “What would commitment mean if you were in a relationship where you could do whatever you felt like?” Clarice asks. Their relationship finally implodes after Toni has an affair with — who else? — a fellow activist for marriage equality.

The truth is that nonmonogamy does not obviate the demand for fidelity: It multiplies it. “Polyamory is giving me such a sense of expansiveness and freedom!” chirps Sparrow. “Like, what other arbitrary constraints can we let go of?” But heterosexual monogamy is not merely an “arbitrary” constraint: It is, as Engels put it, “the first form of the family to be based, not on natural, but on economic conditions — on the victory of private property over primitive, natural communal property.” (When J.R. confidently informs Alison that monogamy is a “capitalist invention,” they are probably off by thousands of years: If anything, capitalism is an offshoot of monogamy.) That is to say that the monogamous male-headed household has a demonstrable economic purpose; it is not an empty social custom that can simply be sloughed off by acts of intelligence. But neither does the simple fact of having multiple partners allow you, by default, to “live out your principles on every level,” as J.R. seems to think. In a slow-building gag, Alison eventually discovers that an un-neutered billy goat has been swinging his way through the herd, leaving Alison with a rash of unplanned goat pregnancies. That pygmy goats do not do capitalism to each other is a comforting thought as far as it goes; but communism this is not. Whatever ethical nonmonogamy looks like, it is certainly no more naturally occurring than monogamy is. “When I was in a throuple,” recalls Alison’s wife, “it was a full-time job.”

Spent is not so taxing. The novel resolves as if by fiat: Alison turns in her book, watches some birds, picks some flowers; Naomi moves in with Stuart and Sparrow (and Lois and Ginger) without any great upheaval. “Lately, Alison has found herself able to envision a glimmer of life going on,” Bechdel writes, “of the Earth continuing to spin on its axis, of the future arriving one day at a time.” Alison tells her friends that she was paralyzed by the idea that she had to “fix everything” herself; now she knows that she just has to “do something.” Still, I wonder if Bechdel no longer has faith in the “great experiment” of lesbianism. “I kind of miss the days when our culture was small and manageable and we had it all to ourselves,” says Mo’s boss at the bookstore. “Yeah,” Mo agrees. “Now it’s like a big obstreperous teenager making a nuisance down at the mall.” That was 1992. Today, there are more queer-identifying people in the United States than ever. Two-thirds of them are women, and two-thirds of those are bisexual; indeed, if queer women had our own Senate, there would be enough bisexuals to break a filibuster. This has an odd implication: The single largest group of queer people, when categorized by gender and sexuality, is made up of women who like men. Not just men, but not not men, either.

So is lesbianism itself spent? Maybe that’s not such a bad thing. One of the principal subjects of Bechdel’s second memoir, the psychoanalyst D.W. Winnicott, once wrote of the “good enough mother,” the mother who meets the infant’s needs most but, importantly, not all of the time. I wonder if we might think of the good enough lesbian. As Mo and Alison show, the lesbian who rejects the traditional maternal role can end up feeling as if she must mother society itself. This is not always a bad thing: One thinks of the lesbian-run blood drives of the AIDS crisis. But Bechdel also reminds us that the drive to perfect one’s environment — to be one’s own mother — is precisely what produces the crippling feelings of complicity and guilt that plague her characters. Alison is so committed to her ideals that even acting them out feels like a grievous compromise; better to keep them on the wall, like the giant taxidermied moose head that quietly rolls its eyes as Alison thumbs glumly through Capital. Winnicott argued that the good enough mother was also one who, importantly, exposed the infant to the inevitable failures of care — what he very beautifully called “alive neglect.” Perhaps it is salutary to neglect one’s principles often enough to keep from becoming identified with them: not to give them up, but to remind yourself that you could. “If there’s no limits, it’s chaos,” Sydney tells the other dykes to watch out for. “To experience true freedom, some ordering force is necessary.” Then she cheats on Mo.