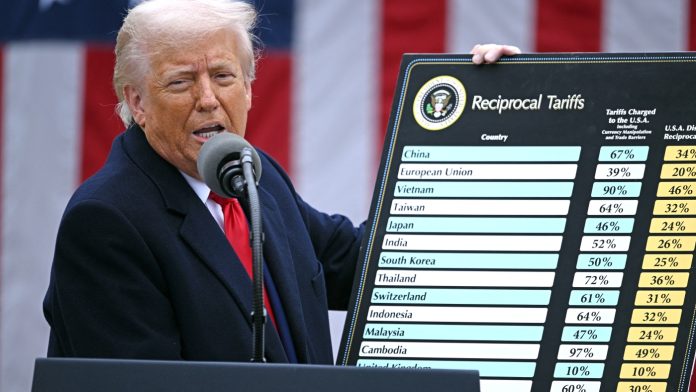

US President Donald Trump holds a chart as he delivers remarks on reciprocal tariffs during an event in the Rose Garden entitled “Make America Wealthy Again” at the White House in Washington, DC, on April 2, 2025.

BRENDAN SMIALOWSKI/AFP via Getty Images/AFP

hide caption

toggle caption

BRENDAN SMIALOWSKI/AFP via Getty Images/AFP

This is an excerpt of the Planet Money newsletter. You can sign up here.

Amid the dizzying trade actions President Trump has taken in recent days, it was easy to miss a remarkable speech the White House released by one of Trump’s top economic advisors, Stephen Miran. In that speech, Miran hinted that the White House might be working to establish a new kind of global economic order that goes beyond just higher tariffs.

As the White House has already made pretty clear, its economic goals include reducing or eliminating America’s trade deficits with foreign countries and boosting domestic manufacturing. Tariffs are one big tool for those goals. But the existing global economic system is built on more than just low tariffs and free trade. It’s built on a special role that the U.S. dollar plays in the global economy. The dollar is the “international reserve currency.” It’s the main currency the world uses to trade and save.

This special role for the dollar can be traced back to 1944. That’s when global financial leaders met at a fancy hotel in Bretton Woods, New Hampshire, and hammered out the details of a new global economic order that would take hold after World War II ended. (For more on the fascinating history of this, read this old Planet Money newsletter and listen to this Planet Money episode).

In this recent speech and previous writings, Miran has complained that — while this special status for the dollar gives benefits to the United States and the global economy — it also strengthens the dollar, making American exports more expensive and U.S. manufacturing less competitive. He has suggested that America basically needs another Bretton Woods-style meeting to reform the international economic system, which would include potentially helping the United States to devalue the dollar or getting the world to compensate the United States for the special role the dollar plays in it. He has dubbed this potential summit the “The Mar-A-Lago Accord.”

Some observers, including Stanford historian Jennifer Burns, believe this idea is actually a primary motivation for Trump’s aggressive tariff policy. That the White House wants to strengthen their hands in negotiations for a grand bargain that serves America’s economy.

Is the special global role for the dollar a privilege or burden?

The reserve currency status of the dollar offers many benefits to the United States. One big one is it gives the United States a financial weapon to sanction other countries, by, for example, cutting their banks off to the flow of dollars or seizing U.S. financial assets, like the U.S. did to Russia after it invaded Ukraine. Because the dollar is the international reserve currency, it’s the lifeblood of trade around the world — even trade that doesn’t involve the United States. Control over the dollar gives the U.S. government a superpower over the global economic system.

Another big benefit of this special role for the dollar is lower interest rates on U.S. debt. People around the world have really wanted dollars and dollar-backed assets like U.S. Treasury bonds, which is how the government issues debt. When we buy stuff from abroad, those countries get dollars, and they need to do something with them. A lot of the time they buy U.S. debt. This mighty global demand for U.S. debt lowers interest rates on it. It’s like the United States has a special, low-interest credit card and can spend like crazy and not face the same financial consequences as other nations. Economists have called this and other benefits the U.S. gets from this system “the exorbitant privilege.”

But in his speech this week, Miran painted the dollar’s reserve currency status as a kind of exorbitant burden. “While it is true that demand for dollars has kept our borrowing rates low, it has also kept currency markets distorted,” Miran said. In particular, with so much global demand for U.S. dollars, the value of the dollar is higher than it would otherwise be. That’s great if you’re an American consumer because foreign imports are relatively cheaper with a stronger dollar, but that’s less great if you’re an American exporter. A stronger dollar means that American exports are more expensive to foreigners.

There’s another sort of weird quirk about having the dollar as the global reserve currency. In what’s known as “the flight to safety,” during times of economic stress, there’s been a tendency for global investors to flee risky assets like stocks and buy “safer” U.S. Treasury bonds. Economists debate whether that’s a good or bad thing, but it means that the dollar tends to strengthen even more during recessions. That’s not great for American exporters, including manufacturers, during hard economic times. (Importantly — and this apparently really scared the White House — during this week’s economic turmoil there was no flight to safety. In fact, there was a flight away from U.S. financial assets. Interest rates on U.S. debt spiked — and people began worrying about a potential financial crisis).

Miran said in his recent speech, the “reserve function of the dollar has caused persistent currency distortions and contributed, along with other countries’ unfair barriers to trade, to unsustainable trade deficits. These trade deficits have decimated our manufacturing sector and many working-class families and their communities, to facilitate non-Americans trading with each other.”

As we’ve covered before in the Planet Money newsletter, Vice President JD Vance has also questioned whether the reserve currency status of the dollar is a privilege or a burden. Last year, when he was a Senator, JD Vance highlighted that the reserve currency status strengthens the value of the dollar. That may be nice for American consumers, who get benefits like cheaper foreign goods and international travel. “But it does come at a cost to American producers,” Vance said. “I think in some ways you can argue that the reserve currency status is a massive subsidy to American consumers but a massive tax on American producers.” This, he suggested, contributes to “our mass consumption of mostly useless imports, on the one hand, and our hollowed-out industrial base on the other hand.”

We spoke with UC Berkeley economist Barry Eichengreen, a leading scholar of international finance and the author of books like Exorbitant Privilege: The Rise and Fall of the Dollar and the Future of the International Monetary System. And we asked him for his perspective on Miran and Vance’s arguments about the costs of the dollar’s special role in the world.

“There is a technical economic term for those arguments: Nonsense,” Eichengreen says.

Yes, Eichengreen says, the dollar is slightly stronger because of its central role it plays in international commerce. “ But that’s like factor number 17 on the list