A groundbreaking study published in the journal Toxins has uncovered a surprising reality: the biological world is teeming with venom delivery systems far beyond the familiar fangs of snakes and stingers of scorpions.

The study, led by William K. Hayes from Loma Linda University, reveals that plants, fungi, bacteria, protists, and even viruses have evolved mechanisms remarkably similar to those of venomous animals – delivering toxic compounds through specialized structures that create wounds in their targets.

“Until now, our understanding of venom, venom delivery systems, and venomous organisms has been based entirely on animals, which represents only a tiny fraction of the organisms from which we could search for meaningful tools and cures,” Hayes said.

For centuries, scientists have primarily associated venom with animals. But the new research challenges this limited view by identifying parallel systems across the biological spectrum that meet the technical definition of venom: a toxic secretion conveyed to internal tissues via the creation of a wound.

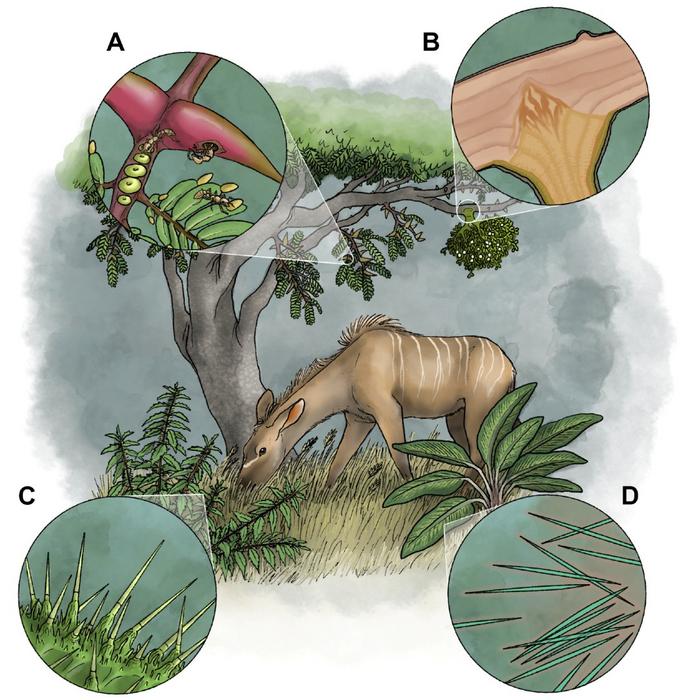

Among the more surprising findings is that some plants employ venomous defenses through multiple mechanisms. Stinging nettles, for instance, use hollow, needle-like trichomes that break off in an animal’s skin to deliver pain-inducing chemicals. Other plants harbor colonies of stinging ants, providing them with homes and food in exchange for protection against herbivores.

Even parasitic plants like mistletoe could be considered venomous, as they penetrate host plants using specialized root structures called haustoria that secrete enzymes to degrade cell walls while delivering toxic compounds.

The study outlines how certain fungi use specialized cells called appressoria to penetrate plant tissue and deliver toxins, while predatory fungi employ a range of capture devices to ensnare nematodes.

Perhaps most fascinating is the researchers’ inclusion of bacteriophages – viruses that attack bacteria – as potentially the most abundant venomous entities on Earth. These viruses attach to bacterial cells and inject their DNA through needle-like apparatuses, leading to cell destruction that “rivals that of many conventional venoms,” according to the study.

The research began over a decade ago when Hayes, who has extensively studied rattlesnake venom, started questioning traditional definitions while teaching courses on venom biology.

“We’ve only scratched the surface in understanding the evolutionary pathways of venom divergence,” Hayes noted.

This expanded perspective on venomous organisms could have significant implications for medical research. Animal venoms have already yielded numerous therapeutic compounds, including medications for treating hypertension, diabetes, and chronic pain. Opening the search to include non-animal venoms could potentially multiply the sources for discovering new drugs.

The researchers hope their work will encourage cross-disciplinary collaboration, bringing together specialists from formerly separate fields to develop a more comprehensive understanding of how diverse organisms have independently evolved venom delivery systems.

As the paper’s whimsical title suggests – borrowing from Disney’s “It’s a Small World” – there’s a unifying element to this discovery. In the words of the researchers: “There’s so much that we share, that it’s time we’re aware, it’s a small world after all.”

If you found this reporting useful, please consider supporting our work with a small donation. Your contribution lets us continue to bring you accurate, thought-provoking science and medical news that you can trust. Independent reporting takes time, effort, and resources, and your support makes it possible for us to keep exploring the stories that matter to you. Thank you so much!