CNN

—

Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson’s dissenting opinions have provoked criticism for their casual and even disdainful tone. She’s called colleagues “hubristic and senseless” and added sarcastic asides.

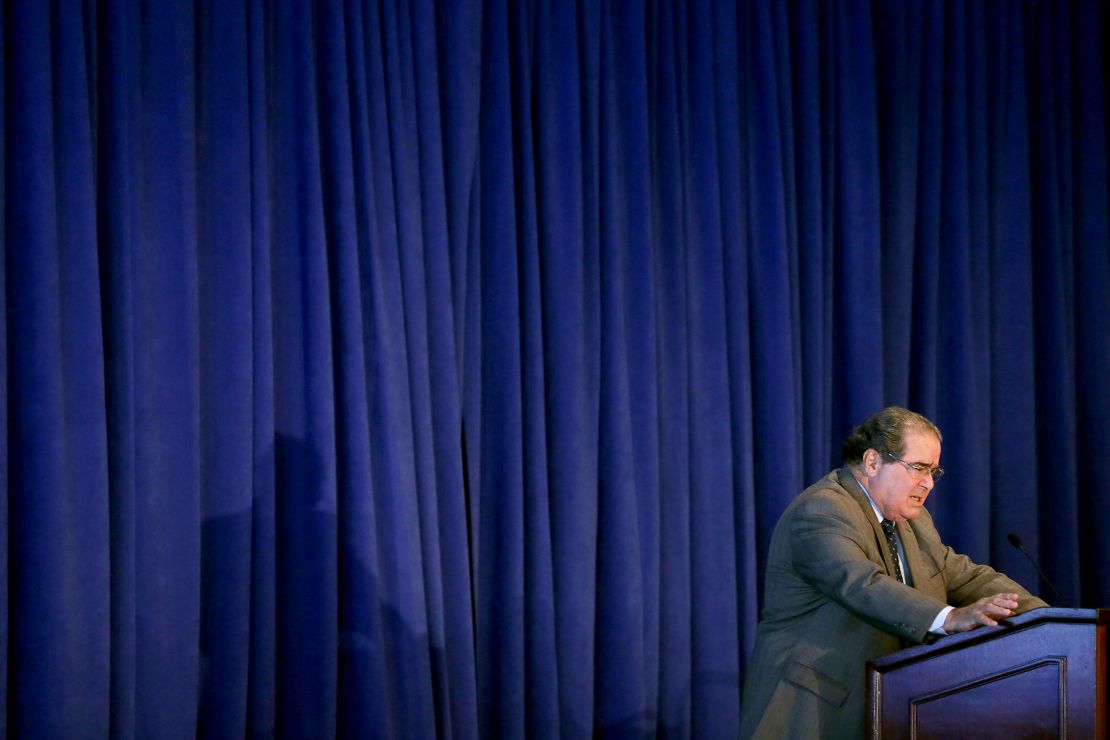

But she is not the first Supreme Court justice in recent decades to rouse the public with cheeky rhetoric. The late Justice Antonin Scalia was a master of the put-down, often in such memorable terms as his 2013 ridicule of the majority’s “legalistic argle-bargle.”

The current debate brings to the fore how the nine justices communicate with the public and especially how those on the losing end get their message out as Americans are focused on the court’s response to the aggressive Trump agenda.

When Jackson dissented from the majority’s decision rolling back nationwide injunctions against the Trump plan to end birthright citizenship, she wrote, “(I)n this clash over the respective powers of two coordinate branches of Government, the majority sees a power grab—but not by a presumably lawless Executive choosing to act in a manner that flouts the plain text of the Constitution. Instead, to the majority, the power-hungry actors are … (wait for it) … the district courts.”

Supreme Court opinions can be dense and difficult for non-lawyers to read. So, a conversational style draws attention, especially if it pitches a few insults with colloquialisms.

As some commentators have noted, Jackson’s use of “wait for it” and, in separate instances, “Why all the fuss?” and “full stop,” particularly offended critics.

But it was Scalia who countered the majority’s reasoning in a 2015 case declaring a right to same-sex marriage with, “Huh?”

Scalia, who served on the court from 1986 to 2016 and whose conservatism was the opposite of Jackson’s liberalism, wrote in that case that he’d rather “hide my head in a bag” than accept the prose of majority author Justice Anthony Kennedy. Separately, in a 2007 dispute, Scalia charged Chief Justice John Roberts with “faux judicial restraint.”

Amid today’s social media toxicity and President Donald Trump’s nonstop name-calling, such judicial insults pale. But certain expectations exist with the language of law.

“On the whole, judicial writing is extremely staid, to the point of being boring,” said Bryan A. Garner, a widely cited legal scholar who has authored several books on judicial writing and jurisprudence. “And when a judge writes in a more pointed, powerful, colloquial style it certainly gets people’s attention, and the more stodgy lawyer-types are going to say, ‘Oh my goodness, this is inappropriate.’”

Reactions to breezy or even brazen language in rulings can cut two ways. Such wording elicits more notice but can mean the author’s views are dismissed out of hand. Naturally, many critics of Scalia’s style were liberal, while many of Jackson’s are conservative.

The current attention on justices’ opinions also flows from the public’s interest in whether the Supreme Court will serve as a check on the administration’s excesses. Dissenting liberals have seized on that interest, employing everyday language to make their positions known.

“Other litigants must follow the rules, but the administration has the Supreme Court on speed dial,” Justice Sonia Sotomayor wrote in one choice dissent joined only by Jackson.

At the Supreme Court, a majority opinion necessarily needs at least five votes, so the author tends to stick to subdued expressions to avoid turning off any crucial justice. And those who’ve lost have more reason to be linguistically fired up.

In the court’s recently completed session, the six Republican-appointed conservatives controlled the most closely watched cases.

Jackson, named by President Joe Biden in 2022, is not just one of the three outnumbered Democratic-appointed liberals. As the newest justice, she also has the least seniority, speaking last in the justices’ private meetings and voting last.

She has, however, made several moves to ensure that her views are not lost. She speaks and writes more than most of her colleagues. She has heavily promoted a memoir she began writing as soon as she took the bench.

And Jackson’s predictions are more dire.

“Perhaps the degradation of our rule-of-law regime would happen anyway,” Jackson wrote in her June 27 dissent in the case related to Trump’s effort to end birthright citizenship. “But this court’s complicity in the creation of a culture of disdain for lower courts, their rulings, and the law (as they interpret it) will surely hasten the downfall of our governing institutions, enabling our collective demise.”

Fellow dissenters Sotomayor and Elena Kagan declined to sign on. Justice Amy Coney Barrett, who wrote for the majority, dismissively rejected Jackson’s line of reasoning and mocked her rhetoric, adding, “Rhetoric aside, Justice Jackson’s position is difficult to pin down.”

Earlier, in April, in another solo dissent, Jackson invoked the court’s notorious 1944 case of Korematsu v. United States, when the justices upheld the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II.

Jackson derided the court majority’s decision to let the administration use the 18th-century Alien Enemies Act to deport Venezuelan nationals to El Salvador. The majority had acted swiftly on the administration’s appeal in the controversy over the 1798 wartime law, issuing an unsigned, brief four-page opinion.

“At least when the Court went off base in the past,” Jackson wrote, “it left a record so posterity could see how wrong it went.” In the controversy at hand, Jackson noted, the court decided the matter without the usual briefing or public arguments, leaving, as she wrote, “less and less of a trace. But make no mistake: We are just as wrong now as we have been in the past, with similarly devastating consequences. It just seems we are now less willing to face it.”

Fellow dissenters in the Alien Enemies Act case declined to join her words.

In a separate instance, Sotomayor, who has been most willing to sign Jackson’s dissents, conspicuously separated herself from a Jackson gibe against Justice Neil Gorsuch and his textualist approach for the majority in a case involving the Americans with Disabilities Act.

There may be a fine line between sarcastically denigrating reasoning and denigrating a colleague. Five years ago, when Justice Elena Kagan wrote an acerbic dissent in a dispute over the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, all three of her then-fellow liberals signed on.

“What does the Constitution say about the separation of powers—and particularly about the President’s removal authority? (Spoiler alert: about the latter, nothing at all.) The majority offers the civics class version of separation of powers—call it the Schoolhouse Rock definition of the phrase.”

For his part, Garner says separating criticism of judicial thought from criticism of the judicial thinker is nearly impossible.

Regarding denunciations of Jackson, Garner said, “It may be that the criticisms are so exercised because her arguments seem so effective. And therefore, instead of addressing the substance of them, people are attacking their form. People did the same thing with Justice Scalia.”

(Garner co-authored two books with Scalia, “Making Your Case” and “Reading Law.”)

Trump’s return to the White House has no doubt intensified the politically charged atmosphere around the court and the executive.

Norms have evolved in all ways. Back in 1947, the first Justice Jackson — Justice Robert H. Jackson — expressed what critics at the time deemed scathing contempt for his colleagues, as he declared in the regulatory power case of Securities and Exchange Commission v. Chenery Corp.: “I give up. Now I realize fully what Mark Twain meant when he said, ‘The more you explain it, the more I don’t understand it.’”

That, Garner said, was what once amounted to nearly intolerable disrespect.