I’m a Libra.

What does that mean? If you’re an evidence-based thinker, it means nothing. If you’re a believer in astrology, however, it means I was born at a time of the year when the sun’s influence on me (unidentifiable and uncertain and unexplainable as it is) was ruled by the Libra “sun sign,” although that sign’s relation to the actual constellation of Libra is fuzzy at best. If you do believe in astrology, you and I should have some words.

But what does it even mean to say the sun is “in” Libra? Why place importance on that constellation and not, say, Orion, which, in nearly all ways, is objectively cooler?

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

It boils down to two things: our solar system is flat, and motion is relative.

Let’s tackle the “relative motion” part first. Consider our own familiar Earth, for example. Our planet revolves around the sun once per year. From our point of view, stuck on Earth, it looks like the sun goes around us once a year. Physically, that’s not the case, but perceptually, it is—which, heliocentrism aside, is why we still geocentrically say “the sun sets” rather than something like “Earth turns such that the horizon rises to block the sun.” Fair enough—we don’t viscerally feel Earth spinning once per day or revolving around the sun at 100,000 kilometers per hour.

Other stars are much, much farther away than the sun, so they appear fixed in the sky relative to one another. Our meaning-seeking brain naturally interprets patterns in these “fixed” stars as recognizable figures that we call constellations (literally, “collections of stars”). Well, they’re mostly recognizable: while Orion does look like a human and Scorpius does resemble a scorpion, Libra is comprised of just four main stars in a wonky rhombus.

As Earth spins, we see these stars rise and set every day. If Earth were fixed in space relative to the sun, we’d see the same constellations in the sky every night all year. Instead, because Earth moves around our star, from our perspective, the sun is constantly moving through a backdrop of constellations, taking a full year to travel all the way around the sky and return back to the place it started.

Here’s where the flatness of our solar system comes in. Earth, like all the other major planets, orbits the sun in a flat, nearly circular ellipse, so the sun’s apparent motion against the fixed stars traces a line around the sky—an ellipse with Earth at the center. We call this path the ecliptic.

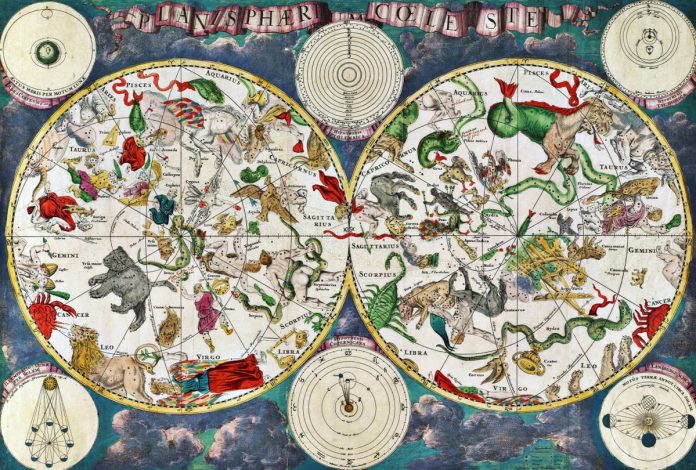

That motion doesn’t change appreciably year after year, century after century; the sun follows the same well-worn path through the same constellations. The names are familiar: Aries, Taurus, Gemini, Cancer, Leo, Virgo, Libra, Scorpius (not “Scorpio,” please), Sagittarius, Capricornus, Aquarius and Pisces. Many of these constellations represent animals, and the ancient Greeks called these constellations, collectively, the zodiakos kyklos, or “circle of animals.” From that, we now call it the zodiac.

The sun’s motion through the zodiacal (pronounced zo-dye-a-kul) constellations produces a calendar of sorts; our star is superposed on Pisces in late March, for example. This is complicated in the long run by a wobble in Earth’s rotation called precession, which is caused by the gravitational tugging of the moon and sun. Over millennia, the timing of the sun’s position in a given zodiacal constellation gets thrown off, creating a disconnect between what astrologers call the “sun signs” and the actual constellations. Three thousand years ago, when the signs were first used by the ancient Greeks, the sun was indeed in Libra in late September. But because of precession, that has since changed, so our star was actually in the constellation of Virgo when I was born.

It’s important to understand that the constellations we recognize are not natural but a product of random star placement filtered through the human brain’s proclivity for pattern recognition. Sometimes different cultures see different patterns, and it just so happens that many modern societies mostly use the same ones as the ancient Greeks. But even then, the origins are a little fuzzy. For example, the Greeks considered Libra to be a part of Scorpius—its claws, specifically—while the Babylonians thought Libra to be a scorpion-free balance, or set of scales.

This means the ancient Greeks thought there were only 11 zodiacal constellations, not 12, with Libra being introduced only much later to round them out to an even dozen.

But it gets worse. The actual path of the sun, the ecliptic, passes through more than just those 12 constellations. Ophiuchus (“the serpent bearer”) is between Sagittarius and Scorpius, and the sun actually spends about 20 days—most of a month—inside its borders. That’s longer than the sun spends in Scorpius! So Ophiuchus arguably deserves to be in the zodiac more than some venomous arthropod, but it happens to contain fainter stars in a vaguer pattern, so it is left out.

And we’re still not done, because while the solar system is flat, it’s not perfectly so. In other words, the other planets orbit the sun largely in the same plane as Earth but not exactly. Jupiter’s orbit around the sun is tipped relative to Earth’s by a little more than a degree. Venus’s is tilted by more than three degrees. The moon’s orbit is inclined by more than five degrees! That means the moon and planets can appear well north or south of the ecliptic, and they can occasionally be inside the borders of other constellations outside the canonical 12 zodiacal ones. There are fully a dozen more constellations that the moon and planets can move through, including Canis Minor, Pegasus and even our old friend Orion.

So no matter how you slice it, the zodiac—from the member constellations to even the meaning that our pattern-projecting brain assigns to those particular groupings of stars—is made up.

This doesn’t mean the zodiac is not a useful construct. It is! Just like the other constellations, the zodiac provides a framework we can use to navigate our way in the sky. For an astronomer with some familiarity of the heavens, knowing that Jupiter is in Taurus (it is as I write this, for example) means the giant planet is visible in the fall and winter after sunset because that’s when the bull-shaped constellation is most easily observed in the Northern Hemisphere. If you want more detail, there are any number of coordinate systems we can use to zero in on a particular position, but if you just want to go out and be under the night sky, the zodiacal constellations offer a “good enough” set of celestial directions. Plus, many of them contain bright stars in obvious patterns that are easy to spot and identify, so observing them is fun.

And that’s no Taurus.