The week when the transition team of President-elect Donald Trump named a TV journalist as defence secretary and revealed that the world’s richest man would be heading up a new department of governmental efficiency felt like a harbinger of regime change. Joe Biden was hailed in 2020 by relieved liberals as a course correction after the first Trump presidency. He now looks less like the upholder of America’s eternal mission to spread freedom around the globe, and more like the end of its ancien régime.

Yet today’s ancien régime once promised the world its future. The French writer and politician François-René de Chateaubriand spoke for many in 1825 when he described the invention of representative republicanism in the US as “the greatest political discovery” of modern times. “The formation of this republic,” he wrote, “has resolved a problem that was thought to be insoluble”: how to allow millions of people to live together under democratic institutions. The New World presented an ideological alternative to the Old World of bewigged monarchs and reactionary aristocrats, one that showed Europe’s masses an alternative and more inclusive path forward.

From the time when Europe’s Great Power system collapsed in war in 1914-18, grand claims were made for the transformative international power of America. Woodrow Wilson pledged to make the world “safe for democracy”. Hitler warned Europeans that Nazi ideas of racial purity were all that stood between them and godless transatlantic degeneracy. Cold war America aspired to forge a Free World of prosperous mass democracies, and President Ronald Reagan famously extolled the US as a shining city on a hill — an open sanctuary at the centre of a world thriving in commercial and cultural exchange.

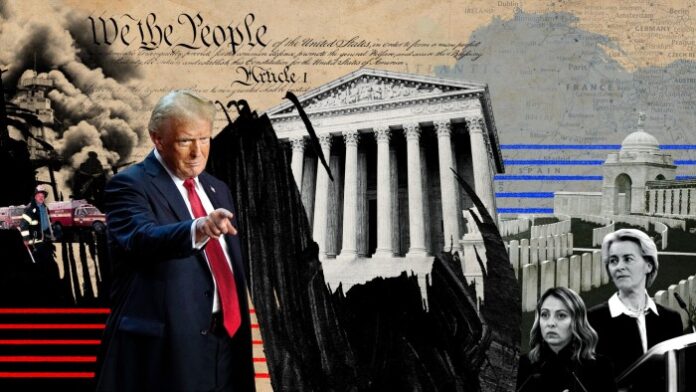

© Jim Bourg/Redux/eyevine

The American century ended much as it had begun, with Clinton advisers hailing the US as “the worldwide symbol of opportunity and freedom”. Many believed that the Washington Consensus would set the new rules of the economic game and liberal democracy would flourish even in the birthplace of Bolshevism. Today that looks like hubris. Since the 2007-08 financial crisis, the number of democracies around the world has fallen, and the backlash to globalisation has gathered pace. American voters themselves this time round welcomed a programme based around trade protectionism, immigration controls, and opposition to multiculturalism.

Yet even in these very changed circumstances, it is hard to break the habit of seeing the US as a kind of precursor. If the US was once a beacon of liberty and hope to the world’s “huddled masses yearning to breathe free” (in the words engraved on the Statue of Liberty), does the 2024 election imply that a different, perhaps more authoritarian future lies ahead for everyone? Naturally, people interrogate the past to try to figure out such questions and ask history to help them make sense of what is happening. In particular, they look for analogies.

The analogy of choice these days is fascism, not surprisingly perhaps in an era of strongmen in countries such as India, Russia, Turkey, and Hungary. Some see fascist dictators between the two world wars as their forerunners. Historian Timothy Snyder posits much more than mere resemblance, asserting that Trump is “the presence of fascism”. Former White House chief of staff John Kelly has said that his ex-boss falls under “the general definition of fascist”. The prospect may be alarming; but it has the merit of familiarity.