On Friday, President Donald Trump said his administration would proceed with his executive order denying citizenship to children of immigrants who are not permanent residents or citizens after the Supreme Court ruled that nationwide injunctions blocking that order had been overreach by district court judges. What has been somewhat lost in the conversation around universal injunctions and the Supreme Court majority’s refusal to address the merits of the case is that the order itself is based on an inaccurate history of the 14th Amendment and of immigration in the United States. Challenges to the order are now making their way through the courts. Those justices who claim to believe in a jurisprudence of original intent should emphatically vote to strike down Trump’s order.

The language of the amendment is clear: “All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside.”

Supporters of the president’s orders make incorrect linguistic and historical arguments. They argue that the clause “subject to the jurisdiction thereof” excludes immigrants who don’t have permanent legal status. If that were true, then we could not arrest, try, or punish immigrants for crimes committed in the United States, because they would not be “subject” to our court system. If an immigrant committed a crime, the only thing we could do is deport that person. Clearly that is nonsense. No one in the country believes this to be true.

Moreover, the constitutional question is whether the person “born” in the United States is subject to the jurisdiction of the nation, not the parent. The language of the amendment is crystal clear: If you are born here, you are a citizen at birth.

So, who is not “subject to the jurisdiction” of the United States? Diplomats and their families and visiting heads of state have “diplomatic immunity,” so they are not subject to our jurisdiction. They cannot be prosecuted for any crime unless their home country waives the immunity. For example, parking tickets issued to cars with diplomatic plates usually go unpaid and there is nothing we can do about it. In the rare case when a diplomat commits a serious crime, or is arrested for spying, the U.S. can expel the diplomat and send them home. Members of invading armies would also not be subject to our jurisdiction, but since no foreign army has invaded the nation itself since the War of 1812, this is not really a category that matters. In Elk v. Wilkins the Supreme Court concluded that Native Americans living on reservations or on tribal lands in the West were not fully subject to our jurisdiction because of their tribal membership and loyalties. In 1924, Congress passed legislation giving birthright citizenship to all Native Americans born in the United States. Thus, today, under the 14th Amendment and the 1924 statute, all people born in the U.S., except children of diplomats, are citizens at birth.

The president and his supporters, and a few academics, also argue that in 1866 there was no such category as an “undocumented immigrant” because we had open borders. Thus, they claim, when Congress wrote the amendment and the state legislators ratified it, no one could have contemplated the existence of “illegal aliens” living in the U.S.

But this is simply not true.

In 1798 Congress passed a series of Alien Acts that provided for the deportation of aliens living here in time of war. Someone scheduled to be deported who evaded that order would have been an illegal alien living in the U.S. The 1866 Congress knew of this law and could have said the American-born children of such aliens were not citizens. Congress chose not to do this. Ironically, the Trump administration is fully aware of this because the administration has invoked the Alien Enemies Act of 1798 to try to deport “undocumented aliens”—even though we are not at war with any other country. Thus, the administration knows that since 1798 there has been a category of people who are not allowed to be in the country but could have had American children here.

In 1803 Congress passed a law “to prevent the importation of certain persons” into the United States. These included “any negro, mulatto, or other person of colour, not being a native, citizen, or registered seaman of the United States.” Anyone bringing such Black people into the country could be fined $1,000—a huge amount of money at the time—and have their ship seized. This was a ban on free Black people being brought into the country, not slaves. Under this 1803 law, such free Black people were illegally here, and subject to deportation—similar to immigrants who don’t have legal status today. Those that illegally remained were not made citizens under the 14th Amendment, but their American-born children were birthright citizens under the amendment.

An 1819 law to prevent the illegal smuggling of slaves into the United States inflicted severe penalties for illegal traders and authorized the president to establish a process for returning illegally smuggled slaves to Africa. The law also authorized U.S. attorneys to secure illegally smuggled slaves within their jurisdiction until the president could return them to Africa. This law remained on the books until the end of slavery, and under it many Africans were repatriated to the continent of their birth. But hundreds, perhaps thousands, of others were successfully smuggled into the country or disappeared from federal custody and ended up as slaves in the South. These were undocumented immigrants, illegally in the United States. Congress was fully aware of the presence of these people in our nation. Many of these Africans arrived in the 1840s and 1850s and were alive when the 14th Amendment was ratified. They did not become citizens of the nation, but their American-born children did.

Finally, before 1866 there were some categories of immigrants—such as convicted murderers—who could be deported. Those who evaded discovery were illegal aliens, but their American-born children became citizens under the 14th Amendment.

In addition to arguing, incorrectly, that there were no categories of “illegal aliens” in the United States, supporters of the president’s order argue that in 1866 Congress could never have contemplated bans on immigration. That is also absurdly wrong.

Since the 1790s there had been calls for immigration restrictions. In the 1830s and 1840s politicians known as nativists demanded bans on the immigration of Irish people and Catholics. In the 1850s the anti-immigrant Know-Nothing Party elected governors and state legislators. In the 34th Congress (1856–57), Nathaniel Banks, a Know-Nothing, served as speaker of the House of Representatives. In 1856, former President Millard Fillmore, then the Know-Nothing candidate for president, won 21.6 percent of the popular vote and eight electoral votes. All Americans of the time understood that anti-immigrant sentiment was strong and sooner or later there would likely be immigration restrictions.

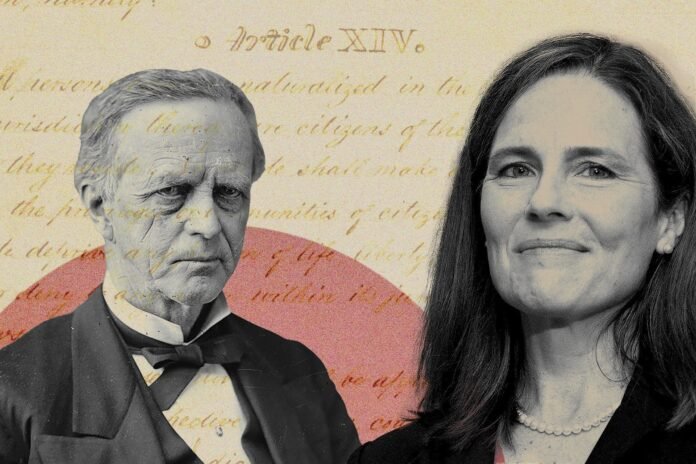

California and Oregon called for restricting or banning immigration of Chinese people while also passing state laws limiting their legal and social rights. Since 1790 federal law had limited naturalization to “any free white person,” thus excluding Black, “Indian” (from Canada, Mexico, or Latin America), Chinese, South Asian, or Pacific Islander immigrants from naturalizing. The 1803 law restricting Black immigration was still on the books. This movement received important support from Chief Justice Roger B. Taney’s assertion in Dred Scott v. Sandford that only white people could be citizens of the United States. Given the recent and ongoing hostility to immigration, it was obvious to everyone in Congress that in 1866 there were people in the U.S. who had no legal right to be here, and that in the future there might be more of them. Their children, nonetheless, became citizens.

The issue of Chinese citizenship, which would eventually lead to a ban on Chinese immigration, came up when Congress debated the amendment. Rep. William Higby of California declared that he viewed Chinese people as “a pagan race” incapable of being citizens. Nevertheless, he voted for the amendment, as did every other California and Oregon Republican, even if they did not like the birthright citizenship provision. Sen. John Conness of California had long opposed immigration by Chinese people. But, during the debates over the amendment, he declared “that the children of all parentage whatever, born in California, should be regarded and treated as citizens of the United States, entitled to equal civil rights with other citizens of the United States.” He asserted that California would be “able to take care” of the Chinese “and to provide against any evils that may flow from their presence among us.” He also said that Californians were “entirely ready to accept the provision proposed in this constitutional amendment, that the children born here of Mongolian parents shall be declared by the Constitution of the United States to be entitled to civil rights and to equal protection before the law with others.”

Sen. Edgar Cowan, a conservative Republican from Pennsylvania who opposed any nonwhite citizenship, directly asked if the 14th Amendment would “have the effect of naturalizing the children of Chinese and Gypsies born in this country.” Sen. Lyman Trumbull, who had drafted the 13th Amendment two years earlier, answered tartly: “Undoubtedly.” No senator contradicted him.

Sen. Trumbull’s position, and the language of the 14th Amendment, was consistent with the English tradition of birthright citizenship recognized in Calvin’s Case, in 1608, that anyone born in Britain, other than the children of a diplomat, was a subject of the Crown and a natural-born citizen. As decided at the beginning of British settlement of North America, every colony and new state followed this rule, as did the national government, for the children of all immigrants and the children of foreign visitors, no matter where they came from, how their parents arrived, or why their parents were here. That is what the Congress in 1866 wrote into the Constitution and what the United States has followed for more than a century and a half.