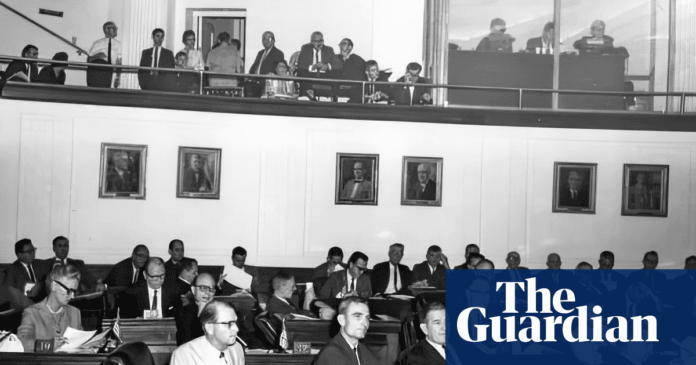

With his second book, Robert W Fieseler casts new light on a dark episode: the years in the 1950s and 60s when the Florida legislative investigation committee, commonly known as the Johns committee, persecuted Black and queer Americans in the name of anti-communist red scare politics.

“The state of Florida has a very poisonous political system,” Fieseler said, promoting a book published as Ron DeSantis sits in the governor’s mansion, whose virulently anti-LGBTQ+ policies had fueled, if briefly, his presidential ambitions.

“Tallahassee politics are nasty. Always have been. There was a small gap, maybe in the 70s and 80s, where decorum and maturity existed, but most of the rules of it are quite toxic.”

Charley Johns was the state senator and governor who steered his eponymous committee. It came into being in 1956, towards the end of the national red scare fueled by the Wisconsin senator Joe McCarthy, and closed in 1965. Hundreds of Black, gay or bisexual Floridians were targeted, most but not all men, many purged from the state education system.

Johns was a Democrat, in the midst of a shift which saw southern reactionaries swap Democratic blue for Republican red. Sixty years on, Fieseler’s book comes out under the second Trump administration, amid attacks on progressive priorities.

“We’re in denial as a society right now that we live in a second red scare,” Fieseler said. “The level of fear now is equivalent or greater to the level of fear felt in the 1950s and 60s.

“I thought this was going to be left-field history. That it was just going to sort of help me sort out my disorientation in this American moment. And then the rise of DeSantisism happened, after I signed the contract for the book. It was shocking: banning AP African American history, attacking the University of Florida, the whole ‘let’s go after Disney’ thing [over its socially inclusive outlook] – that all reinforced the sense that Florida politics are cyclical and certain: everything old is new again.

“When you find a good scapegoat in Florida, you keep the populace in a state of panic and fear, and you manipulate the system to benefit yourself personally.

“Queer folk have been a convenient enemy. Anita Bryant in the 1970s with her anti-homosexual campaign. The rise of Christian conservatism and the Moral Majority, when Jeb Bush played on a lot of anti-gay politics, specifically around the idea of gay adoption. DeSantis is sort of a grandiose revival of all of these unoriginal ideas.

“And the reason all that happened is because the Johns committee was allowed to get away with what they got away with, and that set the stage for future politicians, understanding they probably will be able to do so as well.”

American Scare is Fieseler’s second book, after Tinderbox: The Untold Story of the Up Stairs Lounge Fire and the Rise of Gay Liberation, a story of New Orleans published in 2018. As influences, he cites “nonfiction books that portrayed reality with literary flair, like Friday Night Lights, which I absorbed, inhaled, or John Berendt’s Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil, and what that did for portraying Savannah as a character.”

Accordingly, American Scare contains evocative portraits of Miami, Gainesville and other engines of the economic boom that propelled Florida from agricultural backwater to political power center, alongside compelling character studies of Johns committee victims.

One was the Rev Theodore Gibson, an NAACP leader who championed desegregation.

“It’s important to know this was a man that the Johns committee persecuted,” Fieseler said. “They forced him to testify publicly. They tried to spuriously get him to give away the records of the Florida NAACP, so that they could harass and arrest members. When he refused, they hounded him, threatened him with jail sentences and fines, and then they chased him all the way up to the US supreme court, where he won by one vote.

“He went on to be a Miami city commissioner and died with sort of hero status in the community he loved and helped. But people don’t know about him now. Why? Because his story has long been excised from the official record.”

There is also Art Copleston,“one of the last living Johns committee survivors”, in the mid-50s a student at the University of Florida hauled from an exam room to be interrogated about his sexuality, a horrifying episode Fieseler retells at the start of his book.

Copleston is “in his early 90s now, quite outspoken and brave, and an exception, one of the Johns committee survivors who as part of his lifelong process of recovery from the trauma has to talk in late life about the things that occurred to him as a young man”.

In telling Copleston’s story and others, Fieseler shows the brutal cost of the Johns committee. He does so in such depth thanks to a remarkable act of generosity.

Bonnie Stark was a master’s student at the University of South Florida when she became “the first Johns committee scholar of any note”.

“She learned about the Johns committee initially in a civil rights class, and she became obsessed. She was a child of the Brown decision [Brown v Board of Education, 1954, against racial segregation in public education], she is a civil rights history aficionado, but she was horrified that she hadn’t heard about the Johns committee more, that the red scare had visited Florida, and what went on.

“She devoted close to seven years to it, moving from Tampa to Tallahassee and taking a job as a paralegal so she could be closer to the state archives and what were then closed records. She went and sought out the major players and she was able to win them over. She was the only living person to ever get interviews with Remus Strickland and Mark Hawes, the chief investigator and chief attorney of the Johns committee.”

Fieseler read Stark’s thesis. Reportorial instincts kicked in.

“I’m like, ‘Oh my god, she talked to them,’ and I’m thinking, ‘She’s a paralegal, she might be a pack rat.’ So I reached out to compliment her, and also to see, ‘Hey, do you happen to have those transcripts of the interview with Remus Strickland, or maybe even in the recording?’ And what happened was even better.

“She said, ‘I actually have the secret second set of all the Johns committee records. They’re all in my house, and I want to give them to you.’ I wept. That was out of a clear blue sky. You know, we as journalists and historians, we are little truffle pigs. We look for things and we celebrate the smallest victory. And this was just like, ‘Oh my god, she’s going to give me a war room of information.’ To this day, what motivated her to give someone like me such a gift is overwhelming to think about, because this was her life’s work.”

The records were sloppily redacted. Rather than crawl through state archives, seeking information obscured by design, Fieseler could immerse himself in the Johns committee’s work, reconstructing episodes previously lost to history.

It took six years. The records loom over our conversation, stacked in bankers’ boxes. At mention of the Purple Pamphlet, a homophobic Johns publication from 1964 which backfired, prompting the committee’s demise, Fieseler displays a copy.

“Major individuals targeted by the Johns committee” prominently included Sigismond Diettrich, a prominent geographer who was driven to attempt suicide. But Fieseler also used the records to tell the stories of more obscure figures, “individuals who were informants, and informants who tried to go further and collaborate. It was really sad: the collaborators were usually betrayed by the committee and simply subjected to the same terrible fate as the individuals who didn’t cooperate.”

One thing might be said to be missing from American Scare: a sense that the persecutors ever paid much of a price.

“Charlie Johns did not die in prison,” Fieseler said. “He did not face trial for violations of civil liberties or for betraying his oath to the Florida constitution or its people. The question of the records of the Johns committee being opened up didn’t really arise until he had died. He was never apologetic for what he did to others. I don’t think he understood the degree to which his actions destroyed other lives. I don’t think his ego could process that. He thought he was a chummy good guy who could help out a friend.

“Remus Strickland came up for federal bribery and perjury charges but escaped by the skin of his teeth. He died without fame. Mark Hawes, the chief attorney, had a seizure and died unable to speak.

“So in a thematic sense, time and biology caught up with these men who played around with power as if they would live for ever. But the gears of justice never did spin.”