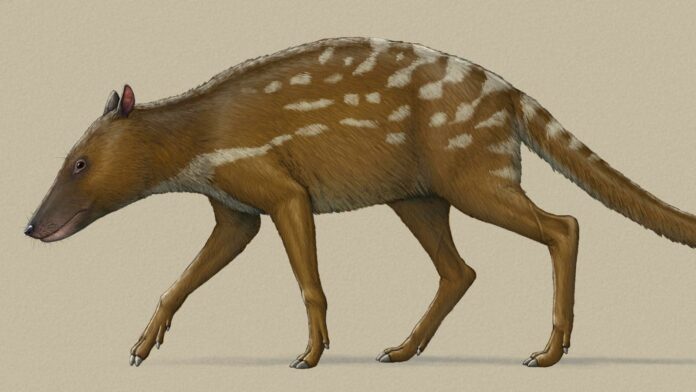

Indohyus looked like a mouse-deer or a large racoon, but had the ears of a whale—and its fossil was … [+]

getty

The evolution of the greatest mammal on earth is a more astonishing transition than one would imagine. Cetaceans—whales, dolphins and porpoises—evolved from the few terrestrial mammals that weren’t impressed with what the land had to offer and returned to the more copious seas. Little is known about this reverse-journey, which has puzzled scientists for decades.

The whale’s closest relatives in the animal kingdom are those that remain on land today. Cetaceans are more closely related to the hippopotamus, or even deer, pig and giraffe, than they are to other marine life. They belong to the order Artiodactyla, which majorly includes mammals with hooves, like ungulates.

This classification was not easy to realize; evolutionary zoologists spent decades pondering where cetaceans came from, as they are not quite like any other marine life or even mammals.

It was in the 1990s that solid research (such as this 1994 study in Molecular Biology and Evolution) finally placed cetaceans in the same order as hippos, ruminants and pigs.

Unbeknownst to scientists in the west, and decades before they realized the connection between whales and pigs, a strange fossil was unearthed. It was found as far away from the seas as you could get—in the western Himalayas of Indo-Pakistan.

The fossil was of the humble Indohyus indirae, which would inevitably become the key to unlocking one of the last land-dwelling ancestors of the whale.

How We Discovered Indohyus

Indian geologist A. Ranga Rao stumbled upon a few unassuming fossils—some teeth and a fragment of jawbone—in the rocky terrain of Kashmir in 1971. Little did he know, these tiny remnants held a monumental secret about the origins of whales.

For years, these fossils lay in quiet obscurity, their significance hidden. It wasn’t until Rao’s widow donated the collection to paleontologist Dr. Hans Thewissen that the true story of Indohyus came to light. Thewissen and his team dug deeper—both literally and metaphorically.

This creature these fossils belonged to was no bigger than a domestic cat and had possibly looked like a chevrotain, or mouse-deer, when it was alive, sporting a long snout and tail, with hooves. It was estimated to be approximately 48 million years old, from the Eocene era.

The world realized the impact of this fossil on our understanding of cetacean evolution in 2007, when an article published in Nature pointed to one little body part of the Indohyus and caused an uproar within the scientific community.

A thick ear bone called an “involucrum” was found on the Indohyus fossil. This bone had only previously been seen in whales and other cetaceans, as it helps them hear underwater.

What was it doing on a land-dwelling ungulate?

The only explanation was that it must have spent time on both land and in water. Indohyus even possessed immensely dense legs, a characteristic seen in hippos. Hippos cannot swim, but use their thick legs to stay weighed down while walking through water. They can hold their breath for up to six minutes if needed.

Another bone in Indohyus’ ankle called the “astragalus” confirmed it to be the closest land-dwelling ancestor of the whales. It also places it within artiodactyls—an additional piece of the puzzle that fit right in.

However, none of this explains exactly how the diminutive creature evolved into massive cetaceans. To put things in perspective, the blue whale is about 15,000 times heavier than its small, deer-like ancestor.

And There’s Also The ‘Walking Whale’

In the same timeline as Indohyus, a closer relative of the whale traversed the seas. It was the first known amphibious cetacean—it spent way more time in the water than Indohyus, but could venture to land if needed.

Ambulocetus natans has been described from just one barely-complete fossil from northern Pakistan.

Ambulocetus natans or the “walking whale” was a 10 feet long mammal, with the body, snout and eyes … [+]

getty

This “walking whale” was about 10 feet long, with the body, snout and eyes of a crocodile. It is believed to have stalked and hunted its prey like one too, peering above the water and clamping down on prey with powerful jaws. Its ears were like those of cetaceans and the Indohyus.

Both Ambulocetus and Indohyus are symbolic of mammals being beckoned back to the seas. Perhaps the seas offered more abundance of prey, less competition for resources or wider avenues for movement and exploration. The adaptations evolved by both species pointed to a shift in the diet from terrestrial to aquatic prey.

Over the millennia, as more aquatic-dwelling cetaceans like the Basilosaurus (and eventually the whales and dolphins of today) began to evolve and thrive, there was no going back. Cetaceans were here to stay in the marine biome.

The journey of cetaceans back to the sea reminds us that life is constantly adapting to its environment, often in ways we might find surprising. Learn about yourself and reflect on your own connection to the natural world by taking this test here: Connectedness To Nature Scale