Getty Images

Getty ImagesThere is considerable speculation that Iran might retaliate for the US’s strikes on its nuclear facilities by closing the world’s busiest oil shipping channel, the Strait of Hormuz.

About 20% of global oil and gas flows through this narrow shipping lane in the Gulf. Blocking it would have profound consequences for the global economy, disrupting international trade and ratcheting up oil prices.

It could also inflate the cost of goods and services worldwide, and hit some of the world’s biggest economies, including China, India and Japan, which are among the top importers of crude oil passing through the strait.

What is the Strait of Hormuz – and where is it?

The Strait of Hormuz is one of the world’s most important shipping routes, and its most vital oil transit choke point.

Bounded to the north by Iran and to the south by Oman and the United Arab Emirates (UAE), the corridor – which is only about 50km wide at its entrance and exit, and about 33km wide at its narrowest point – connects the Gulf with the Arabian Sea.

The strait is deep enough for the world’s biggest crude oil tankers, and is used by the major oil and gas producers in the Middle East – and their customers.

In the first half of 2023 around 20m barrels of oil went through the Strait of Hormuz per day, according to estimates from the US Energy Information Administration (EIA) – that’s nearly $600bn worth of energy trade per year.

That oil comes not only from Iran, but also other Gulf states such as Iraq, Kuwait, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the UAE.

What would be the impact of closing the strait?

Former head of the UK’s intelligence agency MI6, Sir Alex Younger, told the BBC his worst-case scenario in the ongoing Iran-Israel conflict included a blockade on the Hormuz Strait.

“Closing the strait would be obviously an incredible economic problem given the effect it would have on the oil price,” he said.

It would be “uncharted terrain”, according to Bader Al-Saif, an assistant professor at Kuwait University who specialises in geopolitics of the Arabian Peninsula.

“It would have direct consequences on world markets, because you’re going to look at an uptick in the oil price, [and] you’re going to see the stock markets reacting very nervously to what’s happening,” Mr Al-Saif told BBC Newshour.

It would, of course, hurt the Gulf countries whose economies rely heavily on energy exports.

Saudi Arabia, for instance, uses the strait to export around 6m barrels of crude oil per day – more than any neighbouring country – according to research by analytics firm Vortexa.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIran, by comparison, exports about 1.7m barrels per day, according to the International Energy Agency. Iran exported $67bn worth of oil in the financial year ending March 2025 – its highest oil revenue in the past decade – according to estimates by the Central Bank of Iran.

Asia too would be hit hard. In 2022, around 82% of crude oil and condensates (low-density liquid hydrocarbons that typically occur with natural gas) leaving the Strait of Hormuz were bound for Asian countries, according to EIA estimates.

China alone is estimated to buy around 90% of the oil that Iran exports to the global market.

Any disruptions to that could increase fuel and production costs at a time when China is having to rely on manufacturing and exports. That’s not just a domestic problem, either: rising manufacturing costs could eventually be passed on to consumers, fuelling inflation around the world.

The impact could also be outsized for other key Asian economies, which are among the biggest importers, after China. Nearly half India’s crude oil and 60% of its natural gas imports pass through the Strait of Hormuz. South Korea reportedly gets 60% of its crude oil through the strait, and Japan nearly three-quarters.

How could Iran close the strait?

United Nations rules allow countries to exercise control up to 12 nautical miles (13.8 miles) from their coastline.

This means that at its narrowest point, the Strait of Hormuz and its shipping lanes lie entirely within Iran and Oman’s territorial waters.

If Iran were to try and block the 3,000 or so ships that sail through the strait each month, one of the most effective ways to do it, according to experts, would be to lay mines using fast attack boats and submarines.

Iran’s regular navy and the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) navy could potentially launch attacks on foreign warships and commercial vessels.

However, large military ships may in turn become easy targets for US air strikes.

Iran’s fast boats are often armed with anti-ship missiles, and the country also operates a range of surface vessels, semi-submersible craft and submarines.

Experts say Iran could block the strait temporarily, but many are equally confident that the US and its allies could swiftly re-establish the flow of maritime traffic through military means.

The US has done this before.

In the late 1980s, during the eight-year Iran-Iraq war, strikes on oil facilities escalated into a “tanker war” that saw both countries attacking neutral ships to exert economic pressure.

Kuwaiti tankers carrying Iraqi oil were especially vulnerable – and eventually, American warships began escorting them through the Gulf in what became the biggest naval convoy operation since World War II.

Will Iran block the strait?

While Iran has repeatedly threatened to close the Strait of Hormuz in past conflicts, it has never followed through.

Perhaps the closest call was during the tanker war of the late 1980s – but even then, shipping through the Strait of Hormuz was never seriously disrupted.

If Iran delivers on its threat, this time could be different.

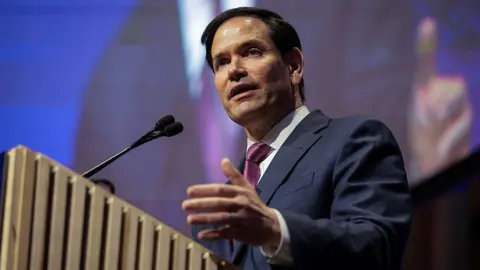

US Secretary of State Marco Rubio has claimed that Iran’s closure of the Strait of Hormuz would amount to “economic suicide”, and called on China, an ally of Tehran, to intervene.

“I encourage the Chinese government in Beijing to call them [Iran] about that, because they heavily depend on the Strait of Hormuz for their oil,” Rubio said in an interview with Fox News on Sunday.

“We retain options to deal with that, but other countries should be looking at that as well. It would hurt other countries’ economies a lot worse than ours.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThough China is yet to respond, Beijing is highly unlikely to welcome any rise in oil prices or disruptions to shipping routes, and could leverage its diplomatic weight to dissuade the Iranian government from going ahead with the blockade.

Energy analyst Vandana Hari said Iran has “little to gain and too much to lose” from closing the Strait.

“Iran risks turning its oil and gas producing neighbours in the Gulf into enemies and invoking the ire of its key market China by disrupting traffic in the Strait,” Hari told BBC News.

Can alternative routes offset a blockade?

The persistent threat of a closure of the Strait of Hormuz has, over the years, prompted oil-exporting countries in the Gulf region to develop alternative export routes.

According to an EIA report, Saudi Arabia has activated its East–West pipeline, a 1,200km-long line capable of transporting up to 5m barrels of crude oil per day.

In 2019, Saudi Arabia temporarily repurposed a natural gas pipeline to carry crude oil.

The United Arab Emirates has connected its inland oilfields to the port of Fujairah on the Gulf of Oman via a pipeline with a daily capacity of 1.5m barrels.

In July 2021, Iran inaugurated the Goreh–Jask pipeline, intended to move crude oil to the Gulf of Oman. This pipeline can currently carry around 350,000 barrels per day – although reports suggest Iran does not yet.

The EIA estimates that these alternative routes could collectively handle around 3.5m barrels of oil per day – roughly 15% of the crude currently shipped through the strait.