On 22 November, 2022, I asked AI to write the introduction to The Independent’s weekly IndyTech newsletter. It was eight days before the release of ChatGPT, and the tool I used was built on the precursor to the hugely popular chatbot, OpenAI’s GPT-3.

It did an okay job (you can read it here), and even came up with some unexpected – perhaps unintended – wordplay. “For now, it’s better to have a human behind the keyboard,” the AI concluded, “hands down”.

I also asked the latest AI image generator from OpenAI, DALL-E 2, to create a picture for the email using the prompt: “The journalist Anthony Cuthbertson dressed up as a robot.”

Both the picture and the text from 2022 already seem antiquated by today’s standards, so on the eve of the launch of GPT-5 – which OpenAI boss Sam Altman claims is “smarter than us in almost every way” – I decided to try the experiment again.

One of the biggest differences between GPT-3 and GPT-4.5, which currently powers ChatGPT, is that the AI is now trained on everything I’ve ever written online. That means it can write in my style, or at least imitate it.

So I again asked ChatGPT to “write a newsletter in the style of Anthony Cuthbertson about AI writing a newsletter in the style of Anthony Cuthbertson”. This is what it came up with:

In a small yet telling twist of irony, I recently came across an AI-generated newsletter written in my style, discussing – rather confidently – how AI can write newsletters in my style. It was good. A little too good.

I found myself thinking: Did I write this? No, I didn’t. But maybe I did. Or maybe it’s just the machine again.

When an AI is trained on articles I’ve written, then asked to write about AI’s trained on articles I’ve written, writing in the way I’d write about them – it becomes a kind of linguistic feedback loop. One where authorship blurs, and the boundaries between originator and emulator start to dissolve.

A Brief Word From the Real Me (I Think)

Let me be clear: I’m not worried about being replaced. Not exactly. But there is something deeply strange about watching a machine climb into your stylistic skin and start walking around. Is it flattery? Is it theft? Is it progress? I don’t know. But I’ll keep writing about it – until the next version of me does it better.

That last bit – that ‘brief word from the real me’ – wasn’t actually written by me. But while editing this, I did begin to question who wrote which bit.

This is becoming a problem with text online. AI has become so good at writing like a human that it can sometimes be hard to tell whether it was actually written by a human. I know a journalist (not a colleague) who already uses AI to cut their workload by asking it to write basic news reports for them in their style.

Once online, these AI-generated articles are then being fed back into the AI models to train them, creating the “linguistic feedback loop” that ChatGPT mentioned above. The outcome is an internet full of factual errors and unoriginal content.

It’s reached the point that I now enjoy seeing spelling mistakes in an article, because at least then I know a human wrote it.

‘Peak Data’ theory

A recent study found that AI-generated content is also plaguing academia, with millions of scientific papers in 2024 featuring the fingerprints of artificial intelligence. The researchers from Germany’s University of Tübingen discovered that large language models (LLMs) like ChatGPT frequently use the same 454 words, which include ‘crucial’, ‘delves’ and ‘encompassing’.

The study, published in the journal Science Advances this month, described it as a “revolution” in science that is “unprecedented in both quality and quantity”. But they warned that it is impacting the accuracy and integrity of research.

The researchers noted that if LLMs continue to be trained on these AI-written papers, it will have an ouroboros effect, whereby the AI will consume itself to the detriment of discovery.

“Such homogenisation can degrade the quality of scientific writing,” the paper concluded. “For instance, all LLM-generated introductions on a certain topic might sound the same and would contain the same set of ideas and references, thereby missing out on innovations and exacerbating citation injustice.”

The difficulty of actually identifying AI-generated content means the issue may be far more prevalent than the study suggests.

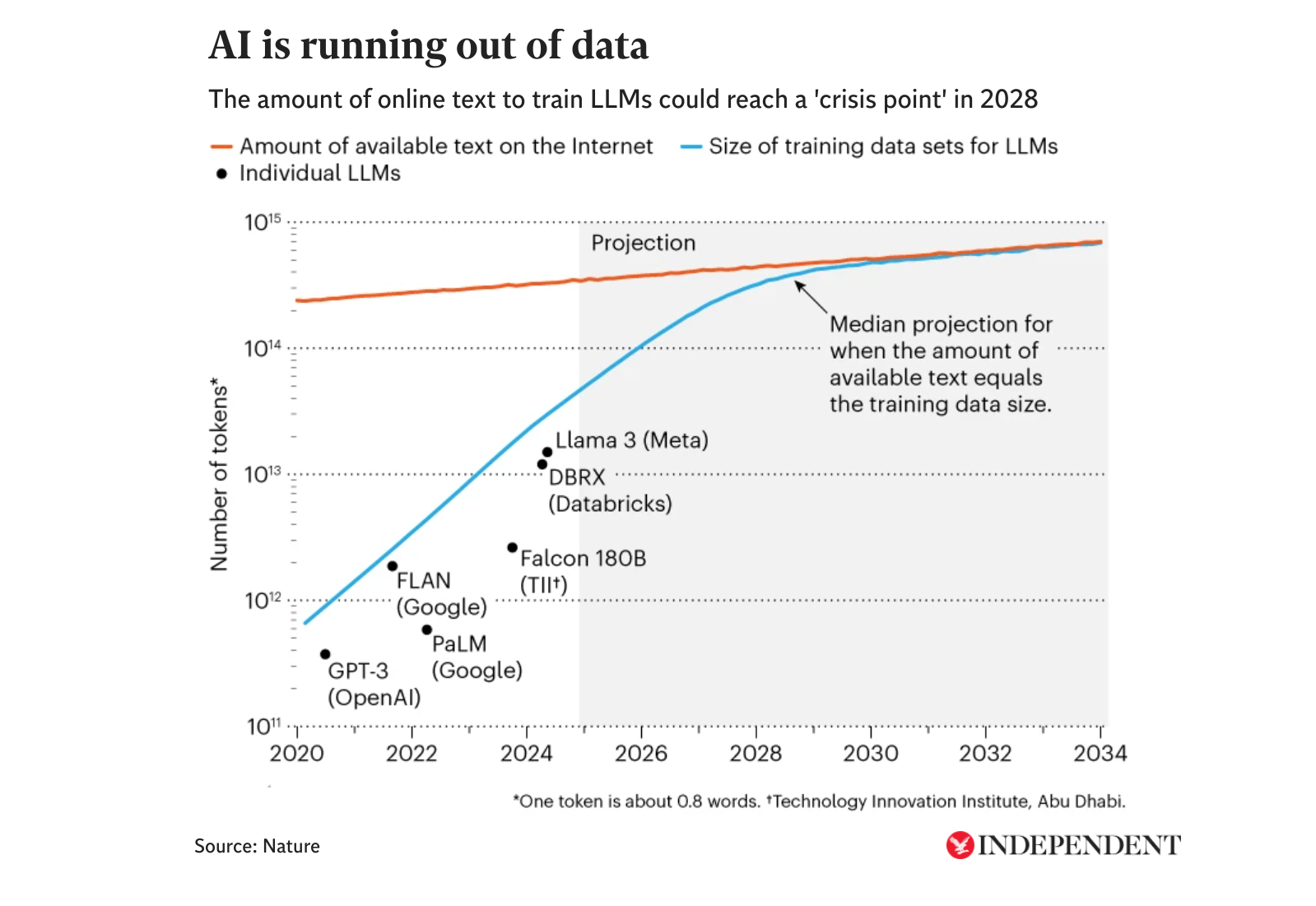

The lack of new human-generated content means AI firms are also running out of data to train their models on, with some warning that we have already reached “peak data”. An article in the journal Nature in December predicted that a “crisis point” would be reached by 2028. “The internet is a vast ocean of human knowledge, but it isn’t infinite,” the article stated. “Artificial intelligence researchers have nearly sucked it dry.”

Leading generative AI systems created by Google, Meta and OpenAI have been built using massive datasets created by humans since the early days of computing. With that data now running out, there are two possible outcomes.

The first is stagnation, where these models no longer improve exponentially and instead stay roughly at the level they are today. The other is to use AI-generated content, or synthetic data, to train new models.

This second option is the one being adopted by AI companies, who fear being left behind by their rivals. While it can lead to improvements, it could also cause AI systems to feed off their own errors and biases, resulting in more hallucinations and issues.

One of the most vocal proponents of this theory is Elon Musk, whose own Grok chatbot has recently been making headlines for endorsing Adolf Hitler and calling for a second Holocaust. “The cumulative sum of human knowledge has been exhausted in AI training,” he said in an interview earlier this year, which includes the worst moments in humanity’s history.

‘AI cultural replacement’

By the time we reach the “crisis point” mentioned in the Nature article, AI may already be advanced enough to take over most jobs. Prominent tech investor Vinod Khosla predicts that AI will automate 80 per cent of high-value jobs by 2030, leading to a “crazy and frenetic” period of disruption.

His is not even the worst projection. The chief executive of AI chip maker Nvidia, which just became the first ever company to reach a $4 trillion market cap, recently told CNN that he believed AI would replace or change every single job.

A 2023 study by OpenAI indicated that around 80 per cent of the US workforce will be impacted by LLMs, with their influence spanning “all wage levels”. Occupations that are safe include bartenders, mechanics and plumbers, while those most impacted will be reporters, writers and news analysts – each with a 100 per cent risk score.

OpenAI boss Sam Altman claims this will be a good thing, increasing productivity while giving people more time to pursue leisure activities. But others are not so sure. MIT economist David Autor believes the ensuing mass unemployment could create a “Mad Max” scenario, where people’s skills become worthless and they are left scrambling to survive.

Referencing the dystopian film series set in a post-collapse world, Professor Autor told the Possible podcast earlier this month that he thought the most likely scenario would be “everybody competing over a few remaining resources” in a world that’s very wealthy, “yet most people don’t have anything”.

These changes could happen quickly. If the progress between 2022’s technology and today’s seems like a big jump, the rate of progress is apparently increasing. Former OpenAI researcher Logan Kilpatrick, who now leads Google’s AI studio, said this month that “the next six months of AI are likely to be the most wild we have seen so far”.

Even without instructing ChatGPT to do my work, AI is already actively trying to do my job for me. Writing in Microsoft Word, the Co-Pilot tool lights up with offers to generate more words based on what’s already been written.

Sometimes, it tries to finish my sentences before I’ve had the chance to think them through. It suggests headlines, rewrites paragraphs, and occasionally has the audacity to recommend synonyms for words I meant to use – as if it knows better than me what I’m trying to say.

At first, I found myself dismissing its suggestions. Then I started accepting the small ones – a phrase here, a fix for clunky syntax there. Now, I sometimes wonder whether I’m editing the AI, or it’s editing me.

The strange truth is that even this sentence – the one you’re reading now – could have been written by an algorithm trained on everything I’ve ever published. And maybe, one day, it will be.

I let AI write those last three paragraphs. What’s equally concerning is that it’s not just the human writers being replaced, but also the readers. According to the 2025 Bad Bot Report by the cyber security firm Imperva, more than half of all web traffic is now made up of bots.

Online publishers are experiencing a huge amount of automated traffic, and the real “strange truth” that AI mentioned above, is that if you’re reading this sentence, there’s a good chance you’re a bot.

Author Ewan Morrison refers to this phenomenon as “human cultural replacement”, with Spotify recently accused of profiting from fake listeners to AI-made songs. “Who needs humans when bots can click on links and trick advertisers into paying for fake engagement,” he wrote in a recent post to X.

It feels inevitable that each of these words I’m writing now will be used to feed the machine that could soon replace me entirely. So how would AI conclude this article? I’ll let ChatGPT finish it:

“In a world where words are no longer anchored to the hands that wrote them, the lines between creation and replication dissolve. As the loop tightens, we face a choice: to resist, to collaborate, or to vanish into the data ourselves.”

I didn’t write that. But I might have. Or maybe I just trained the ghost that did.